By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on October 9, 2014

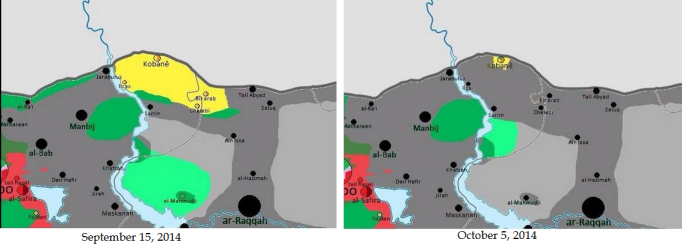

After three-and-a-half years of resistance, the United States finally intervened in Syria on September 23 with airstrikes against the Islamic State (I.S.). The I.S. had begun an attack on the Kurdish-controlled enclave in northern Aleppo along the Turkish border on September 15/16. By October 5, the Kurdish forces had been driven back into the Kurdish-majority town of Kobani (a.k.a. Ayn al-Arab), and I.S. had them surrounded. The desperate scenes of Syrian Kurds fleeing over the Turkish border in the face of the takfiris’ recalls the Iraqi Kurds making a run for the hills after the March 1991 uprising against Saddam Hussein was crushed. Then as now the Kurds believed they had stronger American backing than turned out to be the case.

Qassem Suleimani (right) in Amerli after conquest

CENTCOM announced some U.S. strikes on I.S. around Kobani, but this was rather undermined when the Pentagon spokesman Adm. John Kirby said yesterday, out in public, that “airstrikes alone are not going to save” Kobani, and the U.S. didn’t have a “capable … partner on the ground inside Syria” (nor was the U.S. going to put in its own boots) to stave off this disaster, so “we all should be steeling ourselves for” the fall of the town. Other U.S. officials said that the fall of Kobani was “not a major U.S. concern“. The U.S. overflying Kobani to hit targets in, say, Saraqib, is thrown into sharp relief against the U.S.-provided air cover for Iranian proxy militias in Iraq that have killed hundreds of American soldiers to conquer Amerli, an operation that included Qassem Suleimani himself, the head of Iran’s Quds Force, the foreign service section of the Revolutionary Guards charged with spreading the Islamic Revolution abroad. The news that rebel groups fighting alongside the Syrian Kurds are also not receiving help further creates the impression of U.S. indifference.

Today John Kerry has added to the sense that the U.S. does not care about the fate of Kobani. In a press conference with British Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond, Kerry suggested that protecting Kobani is not a primary objective of U.S.-coalition forces. Kerry said:

“As horrific as it is to watch in real time what’s happening in Kobani … you have to step back and understand the strategic objective … [T]he original targets of our efforts have been command-and-control centres, the infrastructure, we’re trying to deprive the ISIL of the overall ability to wage this, not just in Kobani but throughout Syria and into Iraq.”

The Kurdish areas in Syria are largely controlled by the Democratic Union Party (PYD), the Syrian offshoot of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which has waged a war against the Turkish State since 1984 and is considered a terrorist organisation in the West. There are things to dislike about the PYD, but it should be supported in its fight with the Islamic State.

The alarmist tone in which it has been reported that the U.S. tried to weaken the PYD before accepting their dominance in the Kurdish areas in Syria as a fait accompli and opening a back-channel in 2012 is inappropriate. There was until the summer of 2012 another Kurdish force, the Kurdish National Council (KNC), which was closer with the Western-oriented Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). The PYD and KNC were supposed to jointly manage the Kurdish military forces, the People’s Protection Units (YPG), but the PYD completely hijacked the YPG and in May 2013 blocked the KNC’s KGR-trained militiamen entering Rojava.

The PKK’s mother branch in Turkey was once certainly a Syrian State asset, and the PYD itself has links to the regime. The PYD had been called the “Shabiha of the Kurds“: even after the uprising began, it attacked Kurdish anti-PKK demonstrations and was almost certainly behind the murder of popular Kurdish activist Mishal Tammo. It is also true that the regime has not interdicted the PYD’s recruitment of a militia and the running of a tax system in Hasaka, and continues to pay State employees in PYD/YPG-held areas, rather than rolling barrel bombs into them or using fighter jets or chemical weapons that might make the population, in its desperation, blame the rebels for bringing this disorder on them. It might not be true, as some oppositionists have claimed, that the PYD’s YPG is an “extension of the regime militias,” but it is true that in many ways the PYD is more closely aligned in military terms with the regime than the rebellion—despite local exceptions—and I have never seen a good excuse for the PYD’s leader, Saleh Muslim, blaming the rebellion for the Ghouta chemical weapons atrocity.

That said, while the leadership of the PYD is an authoritarian force against which to be very wary, there are many Kurds drawn into the YPG’s rank-and-file by necessity, and things have run on too far to be too punctilious in the short-term. There is no other option for holding I.S. out of Kurdish areas.

Other than the claim that the U.S. intervention was never meant to save Kobani, the Obama administration has hedged its bets with a scapegoat: Turkey. “There’s growing angst about Turkey dragging its feet to act to prevent a massacre less than a mile from its border,” a senior administration official told the New York Times. “This isn’t how a NATO ally acts while hell is unfolding a stone’s throw from their border.” One doesn’t know whether it is more laughable that the administration should have suddenly discovered the humanitarian calamity in Syria or the bad behaviour of the Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) Turkey. Vice President Joseph Biden’s titanic gaffe this week—not only accusing Turkey of supporting I.S. but saying President Recep Tayyip Erdogan had admitted as much, followed by a swift apology—has also done nothing to help U.S.-Turkish relations.

Erdogan’s reasons for hesitancy, “after all the fulminating” about the need to intervene in Syria, as the administration’s official put it, are not opaque, nor are his conditions. Erdogan spelled out these conditions on Tuesday night:

“The problem of ISIS … cannot be solved via air bombardment. … We wanted three things. No-fly zone, a secure zone parallel to that, and the training of moderate Syrian rebels.”

The training of the Syrian rebels is code for ousting the dictator. Then-Prime Minister Erdogan got well ahead of the military and public opinion in calling for Bashar al-Assad to quit. This was to some degree an impulsive decision: Erdogan’s Foreign Minister was promised to his face by Assad that there would not be massacres of Syrian civilians; when it was found that Assad had lied, Erdogan “adopt[ed] a policy of getting rid of Assad at any cost.” That cost turned out to be very high. More than a million Syrian refugees are on Turkish territory—though let it be said that Ankara has behaved in an exemplary fashion, especially by comparison with Syria’s other neighbours, toward the refugees. There has been terrorism in Turkey, almost certainly orchestrated by the Assad regime, heightened sectarian tensions, and threats to the stability of the Turkish economy, the all-important factor in Erdogan’s government’s success. When Assad brought down a Turkish jet in June 2012, Ankara had every right to expect NATO to enforce its collective security commitments, but pressure from the Obama administration stopped that, and Turkey was left holding the bag with a war spilling onto its territory. Erdogan will not repeat this mistake. Turkey is doing the “bare minimum to get America off its back“.

If Adm. Kirby is correct that ground troops would be needed to save Kobani, Turkey could supply them. A buffer-zone protected by Turkish ground troops is a proposal now more than two years old. But Erdogan is never going to wade into Syria without a guarantee that Washington has too much skin in Syria to walk away—which a no-fly zone would signify—and intends to end the Assad regime. Without such a guarantee, a Turkish intervention could be a debacle that unravels Erdogan’s decade-long project for mastery of Turkey.

Obama is ostensibly committed to bolstering the Syrian rebels as the “best counterweight” to the forces of ruin in Syria. A couple of weeks ago I pointed out:

“Obama has repeatedly said this whenever the public pressure about his lack of a Syria policy has become too much, and every time it has proven a mirage.”

It seems to have happened again. Properly arming the Syrian rebellion and taking ownership of it as an American proxy force is itself a proxy for taking ownership of Syria in toto; it would invest the U.S. in a side in the fighting, and axiomatically commit Washington to the fall of the Bashar tyranny, which it called for in August 2011. That is decisively not what has happened with the much-vaunted $500-million program Obama announced in June for training and arming the rebels.

Yesterday it was reported that the training of Syrian rebels in Saudi Arabia might not even begin for another five months because the vetting and recruitment has yet to be completed. This is a hoary argument for delay, one of the Obama administration’s favourites—and Assad’s. A senior Assad regime defector explained that one reason Assad built up the Salafi-jihadists was because it “creates a dynamic that the internationals can dismiss as too complex or dissonant to Western interests.” This is nonsense of course, as the ex-U.S. Ambassador to Syria, Robert Ford, explained after he resigned in June, noting that the U.S. has identified the good guys “quite well” and has “worked with them for years.”

What, then, is the purpose of the U.S.-led strikes into Syria? To shore-up the designated allies in Iraq, namely the Peshmerga (an actual ally) and the Iraqi government, largely represented at this stage on the battlefield by Shi’ite militias controlled by Iran (not an ally). American officials told CNN yesterday:

“The primary goal of the aerial campaign is not to save Syrian cities and towns … [but] to go after ISIS’ senior leadership, oil refineries and other infrastructure that would curb the terror group’s ability to operate—particularly in Iraq.”

The day after the strikes began in Syria, Lt. Gen. William C. Mayville Jr., the director of operations with the Joint Chiefs of Staff, was quoted saying: “[L]ast night’s campaign was about … simply buying [the Iraqi government and the Peshmerga] some space so that they can get on the offensive” against the Islamic State. These initial strikes were “not coordinated with Free Syrian Army brigades on the ground,” they were focussed on the eastern areas of Syria near the Iraqi border, while the rebellion’s main need is assistance in the west, and it targeted things like I.S.’s oil infrastructure where the most immediate effect is a decline in the local economy and I.S.’s ability to stage cross-border attacks—not a strengthening of the nationalist rebels or an irreversible weakening of I.S. inside Syria or otherwise decisively changing the military dynamics in Syria. Whatever the real reasons for striking at the “Khorasan Group,” this is why the price paid in standing among the Syrian rebels and population was risked with such insouciance by the Obama administration: because the strikes in Syria were never about Syria.

There are echoes in this policy of President Obama’s attempt to deal with Pakistan indirectly via a massive commitment to Afghanistan. This carom shot hasn’t worked in the Hindu Kush, and it will not work any better in the Fertile Crescent. The fall of Kobani will not only be accompanied by terrible atrocities—a Kurdish intelligence official said that if Kobani falls “we should expect to have 5,000 dead within 24 or 36 hours“—but will utterly destroy U.S. credibility inside Syria. Every single faction is watching Kobani, and if it is allowed to fall to the Islamic State as U.S. planes fly overhead, then the process well-underway, of people making their plans without reference to the United States, will accelerate.

Some Gulf States—notably Qatar—and Turkey really haven’t been helpful in Syria. Turkey’s open-doors policy for Salafi-jihadists heading into Syria is now returning to haunt her. Yet it is not unreasonable for the Turks, who feel isolated, to wonder, “Why must we choose between the PKK and ISIS?” when asked why nothing is being done about Kobani. A U.S. no-fly zone over north-west Syria and a public renewal of the commitment to see Assad overthrown would unite and mobilise America’s allies, and help bring this terrible war to an end much more quickly. The U.S. actually turned a profit from the first part of the Gulf War because the Gulf States and Turkey were so determined to borrow the U.S. military for the expedition to get Saddam Hussein out of Kuwait; they are if anything more determined to get Bashar al-Assad out of Damascus.

With an irreversible U.S. investment in Syria that intends the ouster of Assad, Turkey could be pressured into enforcing a buffer-zone in northern Syria. This could lay the groundwork for the strategy laid out by Frederic Hof in August. Hof noted that thus far Obama’s policy in Syria had been “consigned to strategic communication and public relations,” but a real policy would begin by moving the exiled Interim Government onto Syrian soil in Aleppo and recognising it as the legitimate government of Syria, which would make the Assad regime and its Iranian-controlled militias, as well as I.S., occupying powers that it was legitimate for the U.S. to destroy by force of arms, helping this embryo government expand its writ across the country with assistance from a Syrian Armed Force trained in exile. This is a long-term, very difficult strategy—which has not been made any easier by refusing to start it for so long—but any serious U.S. policy for Syria begins by saving the nationalist rebels in Aleppo from the dual regime-I.S. onslaught and preventing I.S.’s genocidal conquest of Kobani.

UPDATE: On Oct. 17, General Lloyd Austin, the commander at CENTCOM, confirmed one of the central arguments made here, saying: “Iraq is our main effort, and … the things that we’re doing right now in Syria are being done primarily to shape the conditions in Iraq.” Gen. Austin said the fall of Kobani was “highly possible,” and had a rambling answer as to why the town did not matter to U.S. strategic concerns, and might even be a trap designed to distract the U.S. from its key interests.

Pingback: What To Expect From The Nuclear Negotiations With Iran | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Are Syria’s Rebels Being Sacrificed To Al-Qaeda For Obama’s Détente With Iran? | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: A Freeze In Aleppo Won’t Help Save Syria—But It Might Help Assad | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Turkey and Saudi Arabia Move Against Assad | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Raids in Syria Can’t Defeat the Islamic State If Obama Continues Alignment with Iran | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: America Sides With Assad and Iran in Syria, Abandons the Revolution | The Syrian Intifada