By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on April 1, 2014

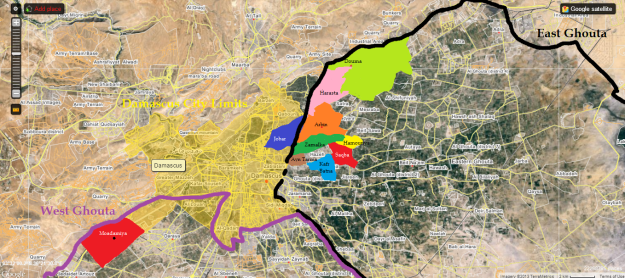

Last September, a Save the Children report noted that children in suburbs of Damascus besieged by the regime were subsisting on “leaves, nuts, [and] fruits”. Throughout October it would become clear that a deliberate terror-famine was being waged by the regime against these rebellious districts, to starve them into submission.

The initial focus was Moadamiya, the one Western Ghouta suburb that was gassed by the regime on August 21. A local resident, Qusai Zakarya, would emerge as a spokesman. In December 2012, the regime had cut off all humanitarian aid. By March 2013, the local stores were empty. People had olives and cured eggplant left. By July, even those minimal supplies had ceased and the only food entering the district was from a very spirited campaign by local residents, who threw bags of groceries from car windows on the Damascus-Quneitra City highway. These bags landed in open fields, which made those trying to retrieve them easy for the regime’s snipers. By September, people were dying—at least eleven women and children. By the end of the year it was more than 200. There was no denying this was official State policy: the heavily-Alawite National Defence Force (NDF)—the amalgamated paramilitary forces under Iranian command that now number over 100,000—was supervised by the Fourth Division, the Praetorian Guard commanded by the dictator’s brother, in enforcing this siege. The purpose was to: “Let them starve for a bit, surrender and then be put on trial.”

With international attention finally drawn to Moadamiya—by, among other things, the fatwa allowing people to eat cats, dogs, and donkeys in extremis—the regime agreed to a ceasefire and to allow “evacuations” on October 13 of women, children and men below 15 and above 65. By the end of the month, about 1,800 people of 12,000 had ostensibly been allowed to leave under deals brokered by Mother Agnes Mariam, the Carmelite (Catholic) nun who had begun her media career by denying regime responsibility for the Houla atrocity. Mother Agnes was quoted saying, “the government considers all those people to be a supportive environment,” and thus it was better if “unarmed civilians surrender and turn themselves in.” The regime solved this little conundrum of why innocent people should be taken prisoner by promptly kidnapping hundreds of the people it had supposedly let go and taking them to the bases of its elite units. This should have been no surprise: Mother Agnes admitted to Zakarya—which he caught on tape—to being in regular contact with Ali Mamlouk, the intelligence chief and the one overseeing the effort at internal repression. By the end of the month about 8,000 people remained in the town.

Mother Agnes Mariam (centre) pictures with Mihrac Ural (left), a Turkish Alawite who led the NDF forces that slaughtered the Sunni inhabitants of Bayda and Baniyas in the Tartus Province on the coast (October 2013)

In desperation, a boy in Yarmouk tries to milk a dog to provide food for his baby brother (February 2014)

On Christmas Day, Zakarya reported that a ceasefire had taken effect in Moadamiya. In exchange for the rebels’ heavy weapons, the people would be allowed food. On January 5, Barzeh acceded to one of these truces. On January 16, the Yarmouk camp followed and received aid for the first time in four months. Perhaps the most humiliating came on February 17 in Babila when rebels were seen embracing the NDF.

NDF member (left) being embraced by a rebel fighter (right) in Babila, Damascus, after a ceasefire (February 2014)

Hassan Hassan laid out the case for these ceasefires being a positive. The civilian population is “ready for peace,” wrote Hassan, and these “[l]imited local cease-fires … can still serve as models” to be extended into a nation-wide ceasefire. The rebels get to keep their light weapons and while they surrender the heavier ones these are not much use anyway due to a lack of ammunition. “[S]ecurity duties are handed over to local rebels,” Hassan added, and “a recognition of local rebels’ strength and popular backing.” Those who would suggest this was a surrender could be contradicted by the presence of rebel weapons and checkpoints: if anything this was the rebels being legitimised, went the argument, accepted by the State as legitimate wielders of force.

But then came the revelations of what had actually happened: salami tactics that piece-by-piece reduced these districts to subservience. On the third day of the ceasefire in Moadamiya, the delivery of food was very severely scaled down—some rice and sugar and scraps of bread. Moadamiya was offered more food if it gave up its armoured truck. Moadamiya obliged. Short-changed again, the regime offered Moadamiya more food if some of the names on the wanted list were turned over to the Fourth Division—for a friendly chat, you understand; a way indeed to erase their names from the wanted list. A great number actually volunteered. A dribble more food was forthcoming. Next came the demand for the small arms, and they too were turned over.

Zakarya could see this happening and did not keep his thoughts to himself. What happened next was as predictable as it was depressing: the population began issuing death threats. They people of Moadamiya have not just been bombarded, attacked with fighter jets and chemical weapons of mass destruction (CWMD), and then starved. They have been humiliated: after incredible resistance they have been brought to their knees, and sued for terms—which they were then prepared to revise downward on their own behalf so the fighting wouldn’t start again and so they could have some food. But they did not particularly like having this pointed out, and they did not like someone endangering the settlement: the regime could cut the food off again and restart the shelling.

This pattern has been repeated in Homs City, where in February a grisly pantomime took place. Having agreed to allow “innocent civilians“—quite an elastic term for a regime that believes rebel-sympathising civilians are fair game—out of the besieged zones on February 6, the Red Crescent vehicles that tried to deliver aid the next day were fired upon, and of the less than 100 people who were allowed out, “All of their names will go to the mukhabarat“. Of the 2,500 to 3,000 trapped people, about 1,400 were released, of which 400 men were taken into custody. On February 14, the U.N. suspended its agreement and the evacuations pending “regularisation” of the kidnapped men. It hasn’t happened yet. Even the U.N. admitted that it was the NDF not the rebels who fired on these aid convoys. There were some who said that the NDF did this on its own authority—by fanatics convinced of the regime’s propaganda that annihilation awaits the Alawis if the regime falls and thus denying any respite for rebels or their supporters, and by cynics as a way of denying Bashar al-Assad any good publicity after he had thrown them into the way of this rebellion. In either event, it meant the regime’s on-the-ground actors wanted the terror-siege in Homs seen through to victory.

This is not lessening. Human Rights Watch makes plain that, despite opening one border-crossing onto the Northern Front—because of the sovereignty issue the U.N. agencies have to ask for Assad’s permission to enter areas he does not control—the regime is deliberately keeping food-deliverers out, often under the pretext of security. Now all pretence has been stripped away: with these ceasefires the regime is “solidifying control of the ring of restive suburbs”; it has succeeded in “starv[ing] rebels and their civilian sympathizers into submission”.

This has been through every stage of the international process. The West has registered protests—John Kerry even wrote an op-ed. The humanitarian organisations have protested. A non-binding statement of the president of the U.N. Security Council has been issued demanding nationwide access. There has even been a Security Council resolution demanding the same—though not under Chapter 7. The regime has refused all compliance to the “international community” and demonstrated, as the chief of staff for the Syrian Opposition Coalition put it, “that the only language they understand is the language of force.” The French have proposed to the U.S. administration that it renew the threat of air strikes in relation to the regime’s continued defiance on the Kremlin-orchestrated CWMD “deal” that spared the regime forcible retaliation for the gas attacks last August. Reasonable as that suggestion is, the urgency of the terror-sieges is much greater. This agreement has turned into exactly the “license to kill with conventional weapons” that the U.N. Secretary-General said it would not. The chemical armaments were always a side-show; murder is being inflicted on an industrial scale without them. If the “Responsibility to Protect” means anything, in letter or spirit, it must mean being unprepared to watch as populations are systematically starved to death. With Russia and China at the Security Council, the regime is immune from international pressure. The only option left is to strike with force to break these sieges. This would not be antagonistic to a political settlement, but part of one. By the Obama administration’s own estimate while the regime is winning it has no incentive to negotiate. If the sieges were broken—and the moderate insurrectionists empowered in both the north and south—this could apply enough pressure to force negotiations. Whatever the outcome of the wrangling over how many and which weapons to send to the rebellion, however, there is no excuse for continued acquiescence to crimes against humanity.

Pingback: Book Review: Cruelty and Silence (1993) by Kanan Makiya | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Obama Is Denying Syria The Weapons It Needs For Its Very Last Chance | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: From Syria To Ukraine, Obama Has Conceded To Putin | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Coming Fall of Homs | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Obama’s Tetchiness About His Foreign Policy Illuminates Its Weakness | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Syria’s Rebellion on the Ropes | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: What Role Do The Palestinians Play In The Jihad In Syria And Iraq? | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Will The Alawis Break With Assad? | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: A Freeze In Aleppo Won’t Help Save Syria—But It Might Help Assad | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: What To Do About Syria: Sectarianism And The Minorities | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: America’s Silent Partnership With Iran And The Contest For Middle Eastern Order: Part Four | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Amerli Shows The Futility Of Aligning With Iran To Defeat The Islamic State | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Syria Awaits The Western Help That Was Repeatedly Promised | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Turkey and Saudi Arabia Move Against Assad | The Syrian Intifada