By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on November 2, 2016

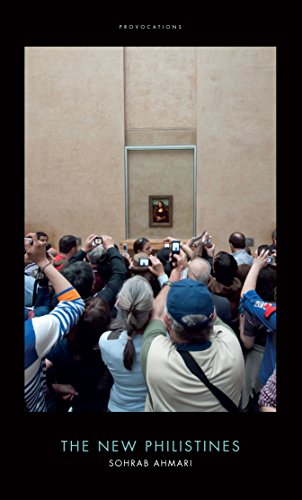

Sohrab Ahmari’s The New Philistines is a crisp and concise polemic. While the book’s focus is “a crisis in the art world,” Ahmari’s dissection of modern art’s failure has implications for the trajectory of the entire liberal Western project.

As Ahmari notes, the complaint that bad art is being considered good is as old as civilization. Ahmari argues persuasively, however, that what is going wrong now is “qualitatively worse than all that came before” because the custodians of our heritage have not redefined the standards of objective beauty and at least a search for truth but have discarded them.

In place of the old standards is a cult of identity politics—a mix of “radical feminism, racial grievance, anti-capitalism, and queer theory”—that has no need for truth-seeking; “truth” is only a means of inflicting upon people an order that is racist, sexist, and homophobic by design, according to the identitarians, which is why their pre-set answers and simply inept art is acceptable, because it advances the cause of challenging this unjust system.

Identity politicization is “one calamity among many” in the art world, yet it has implications far and wide. The identitarians’ own relativistic logic divides the human species into competing tribes whose only interest should be a search for power. With this, the identitarians lay bare their illiberal heart and the danger they pose well beyond the art world.

Ahmari has three chapters. The first covers the reopening of Shakespeare’s Globe and its takeover by the identitarians. The second examines Artforum, the leading contemporary arts magazine in the United States. And in the third Ahmari gives a tour of the London arts scene.

Humility and Power

Shakespeare’s Globe, where many of his plays were first performed, was shuttered in 1642 by the Puritans and re-opened in 1993 after a lifetime of work by Sam Wanamaker. The Globe’s ethos was adhering to the original plays as faithfully as it could. Then Emma Rice took over as artistic director.

Where the Globe had been resurrected on the premise of humility, of acknowledging that the themes in Shakespeare are timeless, Rice’s self-appointed duty was to rescue the Bard, whose work makes her “sleepy,” and make the canon relevant, since she believes its survival this long is due to a conspiracy of silence by people too embarrassed to admit they don’t get it either.

Rice explained how her update to Shakespeare, including sex parity in casting, regardless of relevance to the script, was to be accomplished: “It’s the next stage for feminism and it’s the next stage for society to smash down the last pillars that are against us.”

Notice that the focus is on power and breaking opponents, not art. Notice also how incongruous it sounds when measured against the world we actually live in, which has been so thoroughly rearranged and where feminism’s victory is so complete. It sounds like the crazed speeches of Stalin trying to stamp out what is by then wholly imaginary resistance, with references to the followers of Comrade Trotsky who have infiltrated into upper echelons of the party and even the Politburo.

Permanent Opposition

Here we hit a central theme that Ahmari excavates so well: “Opposing the oppressive mainstream is more important than examining the peripheral as it really is.” The identitarians have come to power but they cannot accept it. This leads, on the one hand, to the permanent revolution aspect of today’s hard-Left or Social Justice Warriors, mining the human experience for ever-more exceptional minorities, and on the other hand an inability to deal with these minorities as they actually are.

Minorities within minorities—atheist Muslims or conservative homosexuals, for example—get very little play in this new politics. But even the majorities within minority categories are not represented beyond mouthing the slogans helpful to the identitarian “narrative”. The actual richness and variety of minority communities is of no interest. The minorities are props—more precisely cudgels—in the identitarians’ imagined struggle against a mainstream that has in fact given way. Despite all its pretentions to transgressiveness—and it can still certainly muster vulgarity when necessary—identitarian art and thought is drearily conformist and alarmingly powerful.

Part of the oppositional posture is a holdover from the identitarians’ antecedents: the 1960s radicals, who had plenty to criticise. The 1940s and 1950s were a time of unprecedented uniformity, and the cultural criticism of the time reflected this. (A famous song referred to everything made of “ticky-tacky” and it all being “just the same”.) This arrangement was an artifice of a societal mobilization to defend even the idea of liberalism, and as Ahmari notes, this liberal order proved spectacularly malleable to the demands made upon it. The civil rights revolution was finally completed legally. Social and legal restrictions on women, homosexuals, and other minorities were lifted. And here was the problem.

The identitarians do not want assimilation, seeing this capacity of Western liberal societies as part of the problem, not part of these societies’ superiority. Eternal opposition is the identitarian posture. The illiberalism of the identitarians can be seen in their having found a system that can accommodate every idiosyncrasy—queerness, if you insist—and determined to work not for its cultivation but its overthrow.

Language and Clear Thinking

Orwell famously drew the connection between muddled thoughts and unclear language, and this feeds back on itself. The identitarian commitment to an obscurantist lexicon leaves them unable to think properly—or really, judging by their output, at all.

Ahmari’s study is a serious look at a creeping authoritarianism that is producing a worrying backlash across the Western world—but he sees no reason to be dull about it, interspersing the narrative with liberal doses of humour, most provided by the identitarians themselves.

Huey Copeland opened a “debate” in Artforum on why “the conversation had changed but the discursive shift doesn’t always correspond to a real shift,” with homophobia, racialism, and sexism allegedly “more spectacularly displayed” today than ever before. In both presentation and content this is sheer piffle. Copeland found himself outdone, however, by Dipesh Chakrabarty, a historian from Chicago University: “It’s not so much a question of commensurating the incommensurable, but of juxtaposing them in such a way that the possibility of commensuration is actually resistant.” Re-arrange that sentence any way you like, it still doesn’t mean anything.

Even more entertaining are the descriptions of the modern artists Ahmari encounters in chapter three. Meineche Hansen’s multimedia art “foreground[s] the body and its industrial complex, in what she refers to as a ‘technosomatic variant of institutional critique’.” Paul Maheke, a French dancer, has his choreography “grounded in emancipatory and decolonial thought with an emphasis on cultural identities and new subjectivities. His current research focuses … on the body as both an archive and a territory, as a utopia to be reimagined through different strategies of resistance.” Doubtless it is believed this unintelligible tripe is profound.

This obsession with pseudo-complex language and ideas is common among relativists and postmodernists in all fields. Bernard Lewis, the great historian of the Middle East, is often attacked by identitarians as an “Orientalist,” a term that had a meaning until it was abandoned by its practitioners for its imprecision. The word was later dredged up and recycled as a term of abuse. In refuting the anti-Orientalist thesis—that all Western intellectual engagement in the region was exploitative in intent—Lewis pointed out that the intellectual centres of study for Arabic were established in the West centuries before the imperialists moved into the East. So either the scholars were very prescient or the colonists extremely dilatory. A postmodernist in the audience congratulated Lewis for discerning the deeper currents of the historic process. As Lewis noted, there are some kinds of nonsense that are beyond parody.

Funny as this is, behind it, Ahmari writes, is an assertion of power. This New Speak—the most important words in which are, Ahmari argues, intersectionality, visibility, individualism, and legibility—is part of the affirmation that a new order has taken hold. There was no debate in Artforum, merely a stream of jargon you can dip in and out of that always flows in the one direction, as Ahmari puts it. Some concepts have now been revised. Visibility, for example, is now seen as the handmaiden of capitalist co-optation: art—both high and low—helped bring minority stories to the fore, the public sympathized, and these groups were brought within the mainstream. For identitarians, as mentioned above, this will not do.

Conclusion

Ahmari is Iranian by origin and notes that soon after the Islamic revolution swept his country the new authorities began purging the country of all external cultural influence, down to blacking out Renaissance nudes in library books. In the fallen Soviet Union, the approved art form was Socialist Realism, which found space for any monstrosity if it promoted the official line. The identitarians are hardly less conformist, even if their methods are more benign.

The uniformity of thought, where apparently nothing except endless grievance Olympics motivates modern artists, should worry, rather than comfort, identitarians. For one thing, it almost certainly means that there are people on the take: when standards have been lowered this far, on condition the art meets narrative needs, then opportunists will take advantage. For another, while it might worry the non-identitarians that the grander questions of humanity are being left out, it should surely worry the identitarians themselves that their movement has turned into a circular firing squad and the revolution is devouring its own in a storm of rows about “appropriation,” the modern term by which what was once called “segregation” has become respectable.

In political terms, too, it has to be noted that the identitarians are destabilizing their own considerable success—and with it quite a lot more than their own comfortable positions at universities and galleries. With their radical attack on the notion of universal truth, whether the question is beauty or biological sex, the identitarians have argued that these things are the result of power structures—which is why it is justified for them to foist upon us their own art that does not even pretend to conform to the old objective standards, because it furthers the cause, it alters the balance of power. But what happens if the mainstream take them at their word, that the only thing that matters is power?

Encouraging the sense that all we are as humans is competing factions in a permanent, zero-sum contest for power seems especially dangerous for minority groups. Perhaps it is inevitable, as white ceases to be a background assumption because of demographic change and becomes a bloc signifier, that there will arise a white identity in the West. Quite a lot rides on the form that takes. At present, the advantage is with authoritarian and demagogic models, and the forces of “correctness” who have employed such methods to press their cause have to take their share of the blame: identity politics, whether in Jugoslavija or America, has only one guarantee—an equal-and-opposite reaction.

What you and Ahmari don’t consider is that the “liberal” values you promote are paradoxical and unsustainable. For example, tolerance leads very predictably to intolerance by privileging (tolerating) intolerant groups. The asymmetry of “tolerance” in the West is also worth mentioning. “No friends to the Right and no enemies to the Left” is the rule aggressively imposed throughout the West. This rule guarantees that politics can only ever move to the Left–hence, the increasing predominance of anti-rational identity politics and the identification of Trump as hard Right, “literally Hitler”–even though Trump is just an anti-immigration populist with loose rhetoric.

On your last point of equal, opposite reaction–I wonder if that’s true. What other group of people outside of Western Europe and its descended nations has decided that “diversity” is a value in itself? They may recognize diversity as a fate, but not as a value. Japan and other Tiger nations are rich and could buy diversity if they wanted it. Some of the mini oil states are rich. All of them signally decline the diversity option. (Singapore may be the lone exception, though it accepts diversity without seeking it.) Can whites ever unify the way that Pakistanis in England or blacks in America unify? I suspect they’ll unify only when it’s too late, after they’ve surrendered their nations. Of course, it might be an interesting experiment to still have some white majority nations a century from now.

LikeLike

A great piece, Kyle. As an artist–or rather, a cartoonist–I have seen a lot of what you described play out in the “Fine Arts” scene.

LikeLike

Pingback: Chelsea Manning betrayed the US and endangered innocent lives – she is no hero - Zimbabwe Consolidated News

Pingback: Chelsea Manning is a Traitor, Not a Hero | The Syrian Intifada