By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 19 August 2018

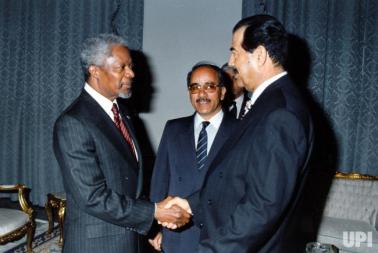

Kofi Annan (picture source)

Kofi Annan, the Secretary-General of the United Nations between 1997 and 2006, died yesterday aged 80. Annan and the U.N. received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2001, and he was credited with “bringing new life to the organization” and emphasising “its obligations with regard to human rights”. The reality was quite different, and Annan’s disastrous record was hardly confined to his time at the helm. Both before (as head of the U.N. peacekeeping department) and after (as U.N. and Arab League envoy to Syria), Annan presided over some of the institution’s worst catastrophes.

SOMALIA AND BOSNIA

Annan was Assistant Secretary-General for the U.N. Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) between March 1992 and February 1993, and then Under-Secretary-General for DPKO from March 1993 to December 1996.

In January 1991, the Communist government of Siad Barre collapsed in Somalia, and the country descended into anarchy and famine. President George H.W. Bush had deployed 28,000 soldiers to Somalia as part of a 45,000-man force. These troops partook in the U.N.-backed Operation PROVIDE RELIEF, providing security for humanitarian relief workers.

When Bill Clinton replaced Bush in January 1993, he began to expand the terms of the mission for the perfectly logical reason that the major impediments to delivering aid were political actors, above all Mohamed Farrah Aidid. In the course of trying to apprehend Aidid, two U.S. Black Hawks were shot down and eighteen Americans were killed by Aidid’s forces, who obscenely mutilated and displayed the bodies in Mogadishu in October 1993. The mission is abandoned soon after.

In his memoir, Interventions: A Life in War and Peace, Annan says that he favoured deploying a larger force and trying to build up local Somali structures, rather than dealing through the warlords, but the U.S. “obsession with Aidid left little space for considering such alternatives.” Moreover, “much” of U.N. Operation in Somalia II (UNOSOM II) was “run by [then-U.N. Secretary-General Boutros] Boutros-Ghali in his secretive style”. Annan had been unaware of the raid to capture Aidid that went so spectacularly wrong and led to the withdrawal of peacekeeping forces. “The world abandoned Somalia”, says Annan, a collective attribution of blame—in contrast to his personal receipt of the Nobel Prize—that occurs time and again when Annan recounts events.

The U.N.’s performance in Bosnia was lamentable. The maintenance of the arms embargo on all of former Jugoslavija locked in the imbalance between Slobodan Milosevic’s regime in Serbia, which had seized control of the Jugoslav National Army, and the Bosnian government, encouraging and deepening Sarajevo’s relations with revolutionary Iran and al-Qaeda.

Bosnia was the largest U.N. peacekeeping mission to date, though peace remained elusive. A U.N.-flagged Dutch contingent handed over the Srebrenica enclave to Ratko Mladic’s forces, and 7,000 people who believed they had U.N. protection were systematically murdered. A three-week NATO air campaign, launched in the wake of the massacre at Srebrenica and in defiance of the U.N., set the conditions to end the war, albeit on regrettable terms.

The Dutch Cabinet accepted responsibility for the Srebrenica calamity and resigned. Annan would do no such thing, expressing only “regrets” at “the failure of the international community to take decisive action to halt the suffering” and saying that the Bosnia experience “was one of the most difficult and painful in our history”—for the United Nations.

It might be said of Somalia and Bosnia that Annan had only institutional or command responsibility, and to a degree this must be conceded. It is also fair to note the degree of powerlessness the U.N. and its officials labour under; this cannot be played both ways, however. Failures cannot be passed to member states and credit claimed by the Secretary-General. Moreover, there are many cases of Annan being personally at fault for disaster, and Rwanda is the outstanding example.

RWANDA

Romeo Dallaire (picture source)

The head of the U.N. forces in Kigali, Roméo Dallaire, wrote to DPKO on 11 January 1994, telling them that a high-level source in the Interahamwe had told him of a plan for “extermination” against the Tutsis, likely to be triggered by the assassination of the Hutu president, Juvénal Habyarimana. The Hutu Power factions planning this also intended to murder Belgian peacekeepers to force their withdrawal, said Dallaire’s mole. Dallaire wanted to raid one of the illegal weapons caches the Hutu militiamen had in Kigali—under the Arusha Accords that defined the U.N. mission, the capital was supposed to be a “neutral zone”, free of weapons—and get the spy out of the country to safety.

Annan’s deputy, Iqbal Riza, signed the response that said both Dallaire’s proposed raid and evacuating the informant were “beyond the mandate” he had, as Philip Gourevitch, an American journalist, records in his book, We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families. Dallaire was told to take this information to Habyarimana, whose associates were behind this criminal scheme, and ask him to investigate. The informant duly stopped informing, and the weapons caches continued to grow.

As Riza makes clear to Gourevitch, it is not as if Annan “was oblivious of what was going on”; the fax was on his desk within forty-eight hours. Later, Annan would refuse to cooperate—and prevented Dallaire from cooperating—with the Belgian Senate investigation into how the genocide was allowed to happen.

Linda Melvern, a British investigative journalist, documented in Conspiracy to Murder the sheer number of times Dallaire warned the U.N., European ambassadors, and anybody else who would listen that something terrifying was coming as violence spiralled in Rwanda between January and the end March 1994. This did not all hinge on one cable. One of Dallaire’s requests for “selective deterrent operations” was rejected by Annan directly in February. Annan told Dallaire that it was the “responsibility of the authorities”—the ones planning the genocide—to keep order.

Dallaire himself, in his memoir, Shake Hands with the Devil, says he told “the triumvirate”—Annan, Riza, and Maurice Baril—that he needed “two battalions and … urgently needed logistics”. Annan “promised to support me”, Dallaire says, though in fact Annan did not support bolstering the small U.N. force in Kigali to try to deter the genocide. Dallaire’s proposal (p. 215) to increase the U.N. troops from 2,500 to 5,500 would never make it to the Security Council. On 21 April, the Council voted to reduce the force numbers to 270.

Events would unfold exactly as Dallaire’s informant had said they would. Habyarimana was killed on 6 April 1994, his plane shot down as it landed in Rwanda, the spark for a 100-day campaign of genocide that killed at least 800,000 people. The next day, ten Belgian “Blue Helmets” were slaughtered after being castrated, and Brussels soon removed its soldiers five days later.

In response to this, Annan writes that DPKO was managing a very large number of peacekeepers—“eighty thousand troops engaged in seventeen peacekeeping operations worldwide”—and refers to “the shadow of Somalia”. The possibility is raised that Dallaire’s spy was supplying misinformation “precisely to trigger the offensive action envisaged by Dallaire and so set a course of events that would restart the war.”

Annan can hardly be given sole blame for what happened in Rwanda. It is true, as he says, that the Security Council was gridlocked: the U.S. had no appetite for another African adventure so soon after Mogadishu, and the French were actively protecting Habyarimana’s regime. But nor can Annan evade a personal role in allowing this hecatomb to unfold, and it was deeply instructive that when Annan acknowledged error, it was to say “the world failed the people of Rwanda” [italics added].

IRAQ

In late 1997, it appeared the United States was on the brink of war with Saddam Husayn. Saddam had tried to assassinate former President Bush in 1993; threatened to re-invade Kuwait in 1994; and all along the way kept up efforts to conceal his weapons of mass destruction programs. With the expulsion of the weapons inspectors in November 1997, it seemed Saddam had abrogated the ceasefire resolution that spared him after the annexation of Kuwait was reversed in 1991.

Kofi Annan meeting Saddam in Baghdad, February 1998 (image source)

In February 1998, Annan journeyed to Baghdad and rescued the dictator. After smoking cigars with one of the most blood-stained tyrants of the twentieth century, Annan announced to a press conference that he had “good human rapport” with Saddam, who was a man the international community “can do business with”. “I think he is serious” about the “process of disarmament”, Annan concluded. Ten months later, after the inspectors were flung out again, Britain and America initiated Operation DESERT FOX, a round of punitive strikes against Saddam’s illegal weapons infrastructure, and an invasion on far worse terms came five years later.

After Saddam was toppled, the full extent of the U.N.’s corruption was laid bare. Money allowed to get to Iraq under the oil-for-food (OFF) program, meant to alleviate the suffering of the Iraqi people under the sanctions, had been syphoned off by Saddam. The Saddam regime used the OFF money internally to build mosques and palaces, and used it externally to finance a political-influencing operation aimed at getting the sanctions lifted. Annan’s own office and family were caught up in the exploitation of Iraq during a time of its most desperate need.

This record might have been expected to induce some humility. It did not. Annan prompted fury in Iraq in 2006 when he said most Iraqis were happier under Saddam’s dictatorship.

IN SUM

Kofi Annan meeting Bashar al-Asad, July 2012 (image source)

There were so many more failures. It was on Annan’s watch that it became clear how riddled U.N. peacekeeping missions and bureaucracy are with sexual abuse, and how little was going to be done about it. Darfur was pulverised and emptied. It was Annan personally who assured the failure of the reunification effort in Cyprus. Being out of office didn’t stop Annan’s anti-talent, either.

When Annan was made the U.N.’s point-man on Syria in 2012, the sense of dread was palpable. Annan correctly identified the removal of Bashar al-Asad and his replacement with a more inclusive, humane government as the sine qua non of progress in Syria, while using up all the time needed to fulfil that objective.

It should be said that after leaving the U.N., Annan did mark down one of his few successes, mediating a settlement in Kenya after the horrendous violence that followed the disputed election in December 2007.

The good intentions of Kofi Annan can be granted and he would still have to answer for the path to perdition he helped pave.

Post has been updated

Reblogged this on | truthaholics and commented:

“The good intentions of Kofi Annan can be granted and he would still have to answer for the path to perdition he helped pave.”

LikeLike