By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 28 July 2020

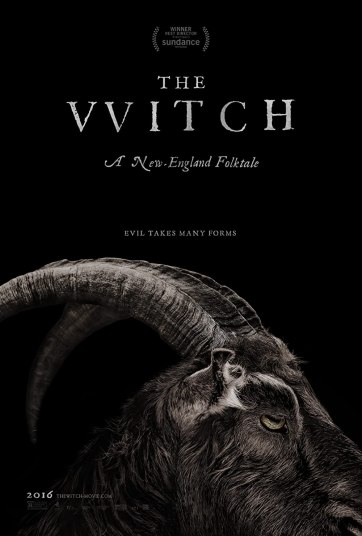

The Witch (2016) is set in the Plymouth Colony, what is now the U.S. state of Massachusetts, in the 1630s. The focus is on Puritanism and the witch craze, subjects that are not entirely irrelevant at the present time.

THE FILM

There are a lot of threads to pull on with the film, but first an overview.

There are a few hundred people at most in the Plymouth Colony, which is essentially a religious commune run by Puritans. The film opens in a court room, with a verdict handed down to banish an Englishman named William, who will not admit error in a religious dispute with the town leaders. William, his wife Katherine, their eldest daughter Thomasin, son Caleb, young twins (Mercy and Jonas), and baby Samuel are forced to find their own dwellings in a forest clearing, setting up a farm, including with three goats (two white females and a black male). What initially seems idyllic goes quickly wrong.

While playing peekaboo on the edge of the forest, Samuel disappears before the eyes of Thomasin. We then see the baby in possession of an elderly, naked women we can assume is a witch, and we then see the pulverised remains of the baby that are being used in some kind of incantation in the shadows (apparently, it is the use of unbaptised baby entrails as an ointment to make her flying stick work). William and his family blame a wolf for taking the baby.

The children are forbidden to go near the forest after this, though William does take Caleb into the woods to hunt for food using metal traps purchased from Indians with a silver goblet that belongs to Katherine, handed down from her father, that she had not agreed to sell; when it is discovered the cup is missing, Katherine suspects Thomasin, and William lets this suspicion stand. Returning home, Caleb quickly concocts a story of thinking he saw fruit in a valley to explain where he was with his father, since his mother spends so much of her days in upset over the lost baby and would not take well to her husband taking another child into the woods.

The next day, Mercy arrives while Thomasin and Caleb are washing clothes in the river. Mercy pretends to be a witch, riding a broom. Told she should not be there, Mercy says Black Phillip, the male goat, has told her she can do as she pleases. Mercy then says a witch took Samuel and she has seen her in the wood “in her riding cloak”. Caleb says that a wolf took Sam. But Thomasin says that Mercy is correct, and she (Thomasin) is the witch of the wood, whose spirit takes leave of her body and dances naked with the devil: she “signed his book” and supplied him an unbaptised baby. Thomasin then says she will disappear Mercy or eat her if she displeases her, and threatens Mercy not to tell their parents. Caleb says she should not have engaged in these “fancies” but does not believe Thomasin and does not tell the parents.

After hearing their parents discuss selling Thomasin to be married in order to rescue them from their perilous situation, Caleb leaves into the woods to check the trap, hoping to find food that will spare his sister this need, but Thomasin finds him as he is about to leave and insists on coming along, as does the family dog. In the confusion after the horse they are riding is spooked by a hare—an animal it is traditionally said witches transform into—Thomasin ends up back home and Caleb is lost in the wood, encountering a young woman in a red cloak who kisses him. The audience is able to see her arm become that of an elderly woman.

William says they cannot ask for help from “the plantation” (Plymouth Colony) because it is more than a day away; to summon help from there would use up all the time and ensure Caleb’s doom. Thomasin then finds Caleb outside in the rain, naked. Brought inside, Katherine bleeds his temple to try to treat him.

Next morning, the twins say Black Phillip told them that Thomasin has put the devil into Caleb and they know she is a witch. Thomasin says this is nonsense and milks one of the female goats, but it produces blood not milk. At that moment, Caleb takes a turn for the worst. Katherine begins to suspect witchcraft afflicts Caleb, rather than a natural ailment. Caleb vomits up a bloody apple and the twins accuse Thomasin of witchcraft in front of their parents. William makes Thomasin swear she loves God and the family prays around Caleb’s bed. But the twins say they have forgotten the words to the Lord’s Prayer, and things get quite hysterical as Caleb becomes clearly possessed and the twins writhe on the floor and scream, too. Caleb seems to recover, then dies after declarations of love for Jesus.

Thomasin flees outside, William follows and speaks to her. William says he cannot keep this secret and a council will be called when they return to the Plymouth Colony, i.e. she will go on trial for being a witch. William says he saw Thomasin stop the twins from praying—after she had taken Caleb into the woods and “found him, pale as death, naked as sin, and witched”. Refusing to listen to her protestations, William calls for her to break whatever bargain she has made with the devil and confess. Thomasin replies that this is not her doing—it was William who took Caleb into the woods, he stole the silver cup and only confessed when it was too late, and he is unable either to grow crops or to hunt, yet too afraid of his wife to tell her this. William says this is more talk from the devil. Thomasin then accuses the twins of consorting with the black goat and says they have cursed the family. William goes to the house to accuse the children of making a covenant with the devil in the shape of the goat and finds them unresponsive. Eventually, they do respond, but only to scream in fright as William shouts at them.

After this second bout of sheer hysteria, William puts the three children in the barn with the goat and nails them inside. The children ask if Thomasin is a witch and she denies it; she asks if they have really been conversing with the goat, and they do not answer. From the barn, Thomasin sees William break down and confess to God that he dragged his family into the wilderness, rather than admit error to the Plymouth council, because of pride, not religious conviction.

Katherine wakes to a vision of Caleb returning to her with Samuel; she says she should wake William to show him the good news, but Caleb tells her not to bother, let him sleep. Caleb hands Samuel to Katherine and she says he is hungry and begins to breastfeed him. Simultaneously, in the barn, an old, naked woman is drinking milk (or blood) directly from the goat. She turns around, scaring all the children. We then cut to Katherine, whose chest is bloody since it is a crow, not a baby, she is nursing. William awakes next to Katherine, who is also awake but does not move. Going outside, William finds the barn with a whole face ripped off, the animals dead and mutilated, the twins missing, and Thomasin just beginning to stir. As William surveys this scene, Black Philip gores him to death. Katherine accuses Thomasin of having killed all the others and attacks her, attempting to strangle Thomasin to death. Thomasin stabs her mother and kills her with a farming tool in self-defence.

After going inside and changing her bloodied clothes, Thomasin falls asleep. When she wakes, it is night time. She goes outside and finds Black Phillip stood outside the barn. The goat goes inside and she follows. Thomasin commands the goat to speak to her as it did to Mercy and Jonas. About to give up waiting for an answer, the goat begins to speak and offers her a good life and the chance to see the world—after she has removed her clothes and signed a book that has appeared before her. Thomasin does so and then wanders into the woods with the goat, finding a fire-based nudist colony that we can only assume is a witch coven, since it soon levitates above the trees, as does she.

Simply as a horror movie, The Witch works very well. It’s tense, extremely well-paced, and earns the few scares that are present. The information necessary to follow it is provided, but with subtlety. And it keeps the audience engaged and working even after it is over—letting them decide if there is any “there” there, or this is all in the imagination of people subjected to the stresses and scarcity of a harsh and unknown landscape, while trapped in a worldview where witches are real—and possibly having accidentally ingested a hallucinogen like ergot, a fungus that is shown on rotting corn at one point. As against thematically similar films like The Blair Witch Project (1999) or the other horror films around that time—for example in 2014: Annabelle, Unfriended, and It Follows—The Witch stands up extremely well.

The director, Robert Eggers, has in a number of interviews described the extent of his research for the film, looking into early English colonial life in America and the ideological currents around Puritanism and witches, and following in some of those footsteps was extremely interesting.

THE PURITANS

The first part that interested me was how the Plymouth Colony in the 1630s fits into the Puritan settlement of the Americas.

The term “Puritan” emerged shortly after Martin Luther’s declaration in 1517 and the onset of the Reformation: it was an epithet for those Protestants who were especially uncompromising in trying to “purify” church services, buildings, and so forth of Catholic influence. In England, the Puritan movement was somewhat tamed in the latter part of the sixteenth century, first by suppression, when Mary I (r. 1553-58) tried to restore England to the Roman Catholic Church, and then under the religious settlement arrived at by 1559 under Elizabeth I (r. 1558–1603) that enshrined significant elements of the Puritans’ Reformed or Calvinist doctrine into the state Church alongside an episcopal structure that was more Catholic.

Tensions between the Church of England and the Puritans intensified during the rule of James I (r. 1603-25) and under his son, Charles I (r. 1625-49), relations essentially collapsed. There was a trickle of Puritans moving to America late in James’ reign, and under Charles, after the closure of Parliament in 1629 and the onset of his eleven years of Personal Rule, this became a torrent. Probably 20,000 people out of a population of four million left England for the New World in the 1630s. In relative terms this is quite small (0.5%), but it would be as if three million people left modern Britain. As a proportion of the population in the Americas, these arrivals were astronomically higher.

English attempts to settle in America began with two Elizabethan efforts in the 1580s to settle Roanoke Island in what is now North Carolina. The one-hundred-plus colonists disappeared, their fate unknown from that day to this: the word “CROATOAN”, carved in a tree, was all that was ever found of them.

Jamestown, Virginia, is the first English colony to stick, established in 1607. Plymouth was established next, in 1620, by the passengers of the Mayflower, and the Colony of Massachusetts Bay was formed to the north after the arrival of the 700 Puritan settlers on the Winthrop Fleet in the summer of 1630.

Most of the Puritan refugees settled in Massachusetts, which had about 20,000 people by 1640, a full order of magnitude more than modest Plymouth, with 2,600 at most. The Virginia Colony, with its capital at Jamestown, had about 8,000 residents. These colonies were formally under charter to the English Crown, but London’s control was more nominal than practical, and this influence from the Mother Country weakened still further as the colonies expanded with these waves of Puritans in the 1630s, people who were specifically fleeing the rule of what they saw as a tyrannical and impious English King.

A significant portion of the New World Puritans returned to England after 1642 to fight for the Parliamentary side of the Civil War in the belief that God’s way might be able to prevail in their homeland, which it did. In January 1649, the King was put on “trial” and “executed”. The Puritan officers who had staged the trial—ultimately led by Oliver Cromwell—proclaimed a Commonwealth, whose brief existence was marked by a chaotic struggle, as the logic inherent in the Puritan camp—that there is always a way to be “purer”—played itself out, and even wilder splinter factions like the Fifth Monarchy Men found space to agitate and a foothold in the New Model Army.

Most Puritans remained in England even after the 1660 Restoration re-enthroned the House of Stuart in the form of Charles II (r. 1660-85). The old state-Puritan tensions returned with the King, especially after the 1662 Act of Uniformity that forced most of the Puritan clergy out of the Church of England altogether, hence Puritans being known as “dissenters” from this point, and later as “non-conformists”. But the tensions never rose to the levels that led into the Civil War. As the names suggest, Puritanism from the late seventeenth century onwards was a marginal cause: its triumph had been its undoing; the English people had experienced their version of Godly rule, and rejected it.

Charles II was a secret Catholic in the pay of the King of France, and this played out in ways that made Puritan life more difficult. This worsened with the accession to power of Charles II’s brother, James II (r. 1685-88), in 1685. An overt Catholic, James II immediately began bringing to life the nightmares of English Protestants, trying to purge the state and society of Protestant influence, roll back the powers of Parliament, and rule in a more autocratic, Continental fashion. Simultaneously, James II tried to combine this Catholic absolutism with outreach to the Puritans. It was a fatal mistake. The reaction of the Whiggish Establishment was swift. James II was put to flight in the Glorious Revolution of 1688-9, and William of Orange (r. 1689-1702) brought over to rule, alongside his wife (and James II’s daughter), Mary II (r. 1689-94). England’s evolution after this was in the direction of an ever-more tolerant policy toward the Puritans.

ACCURACY

So how well does the film stack up against the actual historical record? On this, we have the testimony of Eggers himself. The question of accuracy can be broken up into essentially two: aesthetics and theology.

As Eggers notes, there were certain details changed to the houses—larger windows and more of them, for example—that were logistical in origin, to allow more light and better camera access. The clothes would have been dirtier and more worn, yet also probably more colourful. The greys shown in The Witch, and the common belief that grey is what Puritans wore, are part of the myth solidified by early twentieth century Progressives, summarised by H.L. Mencken, that Puritanism was “the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy”. The dog is clearly of a breed that is anachronistic, as are (probably) the bear traps that William acquires. But in general, the look and feel of the thing is in-keeping with the best sourcing we have for New England in the first half of the seventeenth century.

In terms of the beliefs shown in the film, Eggers explains that while all these pieces—”Satanic goats, covens, naked witches, flying ointments, and witch ointments made from baby entrails”—do occur in the folklore around witches, they are not necessarily common. Most importantly, these elements are even less commonly all “connected in the same narrative”, and that is especially true for the English. Most historians would find the archetypes brought together in this way “too continental for the seventeenth century … It would be appropriate if the story was set in France, Germany, or Sweden”.

The reputation of the Puritans precedes them, but as Eggers’ qualifier here suggests, it is interesting to note the complexities even of the New World Puritans’ worst episodes, such as the Salem witch trials, which are doubtless what the film—with the location in which it is set, and the title—intend to conjure up in the minds of viewers. This is certainly something that could only have happened in the New World with the Puritans, where they were trying to administer Heaven on Earth—not in England, where the Puritans had found terms with an imperfect state—and it works as an artistic device because most people do not know much about these trials: their inherited understanding is that this was a horrific moment of religious zeal and hysteria, and it rarely goes beyond that. It is not that this is untrue, it just needs perspective.

The Salem trials, taking place over fifteen months beginning in February 1692, accused 200 people out of a population of 50,000 and executed nineteen. In other words, the scale is far smaller than what most people imagine. Yet the exact reason that this episode remains in the cultural memory of the Anglosphere and broader West, apart from the fact that it occurred later when there were better records, is that it involved an unusually large number of people by the historical standards of these things and it was against the grain of the time. Salem took place more than half-a-century after the witch panic phenomenon had virtually ceased on mainland Europe, and where it had persisted in Puritan enclaves in America the trials tended to involve two women at most and ended in acquittal three-quarters of the time. Emotional experiences linger in the memory, and it is because what happened at Salem was so shocking to their contemporaries that it has been kept alive. There is also a political reason, because Salem was so useful polemically for the Catholic Church. The Counter-Reformation had been set aside at Westphalia, but the war continued by other means. The Salem events were a strong counter-point to a Protestantism that spoke in “Black Legend” terms about the Roman Church, allowing Catholics to return the accusation of superstition and repression, and to summon the memory of events like the Anabaptists at Munster to argue that Protestantism’s attempt to put doctrinal matters that belong to the Papacy in the hands of individual believers always ended this way, with the triumph of unreason.

PURITANS IN THE PRESENT DAY

The final question thrown up implicitly by the film is what to make of the Puritans now. One argument, for which the evidence is certainly abundant, is that it is the secularized Puritans that imbue American politics with its hysterical quality: the sense that sin is overwhelming the society, which must be remade anew lest a tipping point be reached, and always Armageddon is just around the corner. The classic analysis of this phenomenon by Richard Hofstadter in the 1960s, in his essay, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics”, was centred on the conservative Right and the fear of Communist infiltration, or perhaps better say contamination. The current version of this, with the wokeninquisitors of the Left, is an even more exact parallel with the Puritans and particularly their excesses as shown in The Witch: parts of the anti-Communist Right in the 1960s overdid things, but there really was a significant Soviet espionage apparatus in the U.S.; the current movement of people intent to strip away every last micro-manifestation of sin from the individual and society are doing so at a moment when such sins as concern them have never been more marginal.

It’s not so much a counter-argument as a qualification to point out that the conditions under which the Puritans gave way to madness were so extreme that excesses of some kind would have been inevitable from almost any group of people. The colony established months after Jamestown, in Phippsburg (modern-day Maine), by George Popham, was disbanded within eighteen months after its numbers were decimated by the elements, disease, and fighting with the Indians. The scale of these losses was as nothing to Jamestown itself, which in the winter of 1609-10 experienced what became known as the Starving Time: about 400 of the 500 colonists died and about 40 managed to escape amid scenes of cannibalism. The Plymouth Colony lost half its people in the winter of 1620: within three months of arriving in November 1620, forty-five out of just over one-hundred people were dead; by spring of 1621, less than twenty “able-bodied men” were still alive. The early encounters with the Native tribes largely did not go well and after the Pequot War (1636-38) the interaction in New England largely ceased, leaving the settlers no trading partners and no lines of communication outside their own community. One of the most realistic aspects of The Witch is showing the psychological strain from the pervading sense of insecurity, particularly over food. The early Puritan colonists lived in the constant knowledge that the opportunities for death surrounded them. In a very real sense, the end of (their) world was always very close at hand.

This is not to deny the importance of ideology: it does not matter how isolated a community is, nor how constantly terrified and half-starved it is, there will be no witch trials without a pre-existing belief in witches. This has to be acknowledged as a feature of Puritanism. By the same token, without the belief that it was doing God’s work to set up these pure societies, it is difficult to imagine anyone braving these conditions at all. And even during the worst of it, the project was not just defensive: objective advances in the human condition were made in education, literature, economics—even science and (odd as it sounds to us now) political tolerance. If the negative aspects to American politics are to be charged to the Puritan account, they also have to be debited for the fact that this impulse for work and renewal, an eternal striving for betterment, created the political foundations and cultural habits that led within a short time to the establishment of one of the most successful states in history, whether looked at from the perspective of human flourishing domestically or power projection abroad.

This review was originally published on Letterboxd.