By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 18 March 2021

After the founder of the Islamic State movement, Ahmad al-Khalayleh, the infamous Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, was killed in June 2006, his designated replacement, Abd al-Rahman al-Qaduli (Abu Ali al-Anbari), was in prison. The leadership of “Al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia” (AQM), as the Zarqawists were officially known at the time, passed to a veteran Egyptian jihadist, Abd al-Munim al-Badawi (Abu Hamza al-Muhajir), sometimes known as Abu Ayyub al-Masri. Three months later, a merger process between AQM and its closest allies in the insurgency produced “the Islamic State of Iraq” (ISI), formally inaugurating the statehood project eight years before the caliphate declaration in June 2014.

While ISI covertly maintained a relationship with Usama bin Laden, the advent of the ISI was presented as a dissolution of Al-Qaeda on Iraqi territory, and in fact the group was largely autonomous from Al-Qaeda “Central” (AQC), with the major exception of ISI’s “foreign policy”, which adhered to Bin Laden’s strictures on not attacking Iran, since the country provided the lifeline that enabled Al-Qaeda to function as a global entity. To mark the break with Al-Qaeda, the ISI selected as its leader Hamid al-Zawi (Abu Umar al-Baghdadi), an Anbar native, from a village near Haditha, who had once been a policemen for Saddam Husayn’s regime, until he was dismissed because of his Salafist rigidity in 1993, right on the cusp of changes that would make the Ba’th regime much less sensitive to such beliefs in the security forces.

While Al-Zawi often gets short shrift in the story of the Islamic State—indeed, is often directly disparaged—this is a terrible misreading of the movement’s history.

AN OVERVIEW OF AL-ZAWI’S REIGN

The Zarqawists had been a small, tight-knit, and foreign-led contingent in the early phase of the insurgency, and so long as Zarqawi lived remained foreign-led by definition (he was Jordanian). The U.S. projected this paradigm onto the ISI, believing Al-Badawi was really in control, that the group was merely a front for AQM, and even for a time that Abu Umar was a wholly fictitious character, an actor employed by Al-Badawi to read the speeches that became the main mechanism for the ISI to present its message over the next four years.

But the United States had not taken account of the changes in the nature of the insurgency after late 2005, when significant sections of the insurgency departed the battlefield to get involved in the political process, after concluding the quasi-boycott of the first election in January 2005 had not served the Sunni Arabs well. The homegrown rejectionists thereafter were in smaller groups that gravitated towards Zarqawi, his prestige bolstered by the two 2004 Fallujah battles, among other things. The Zarqawists were becoming more proportionally Iraqi—and larger—with every insurgent group that joined the ranks: the more AQM grew and the more powerful it became, the more it seemed like the only game in town for Sunni Arabs who rejected the post-Saddam order wholesale.

After Saddam went to the gallows in December 2006, the spell was finally broken for large numbers of Ba’thi-Islamists who had truly believed until that moment he could be restored to power. Saddam’s deputy, Izzat al-Duri, pointedly only took on an “official” role in the insurgency after that date, but Al-Duri had always been in an awkward position in dealing with the Islamists he supported—before and after the regime came down—because he was a Sufi. With Saddam gone and the insurgency so thoroughly jihadized by the end of 2006, Al-Duri had limited potential in a competition with the IS movement, a problem compounded by his Naqshbandi Army being essentially a Sufi brotherhood.

Al-Zawi made his first speech exactly a week before Saddam’s execution, laying out the Islamic State’s vision. The next two years were rough for the ISI as the U.S. Surge and Iraqi Awakening eliminated their territorial holdings and ground down the organisation’s leadership and manpower. But Abu Umar continued his speeches, ambiguously claiming the mantle of caliph, and holding the line ideologically. By late 2009, with the new U.S. President, Barack Obama, having diplomatically disengaged from Iraq, and pulled American troops back to their bases, IS was showing signs of life. Political and physical room had opened up for IS, and Al-Zawi took full advantage.

Directed by Al-Zawi, in close coordination with Al-Badawi as his deputy—serving as IS’s “War Minister” and “First Minister” (al-Wazir al-Awwal)—IS began reinfiltrating into old haunts, making restitution with some tribes, finding sympathisers in other tribes. Awakening militiamen were cut down in their hundreds, and the whole Awakening project faltered as it began to be pressed on a second front, by Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, who consolidated a sectarian Shi’a autocracy in Baghdad that saw the Awakening militias not as counter-terrorism partners, but as a coup threat. This was a godsend for IS, politically discrediting the Awakening leadership, which was always a minority among Sunni Arabs in supporting the Americans and the Shi’a-led government over the Islamic State; once the money and protection from the Shi’a militias waned, the natural course was reconciliation with IS. In many cases, younger tribal figures approved IS’s assassinations of their anti-jihadist elders, and these younger figure then brought the tribe (or sections of it) back into the IS fold.

When Al-Zawi and Al-Badawi, “the two shaykhs” as IS often refers to them, met their end on 18 April 2010—dispelling, at last, any doubt about Abu Umar’s existence—it was understood in the U.S. and much of the West as a death knell, part of a trend that would see nearly completely decapitated by June 2010. But it was not the end. The foundations Al-Zawi and Al-Badawi had set down were firm: the new leader, Ibrahim al-Badri (Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi), inherited more favourable conditions than IS had known for nearly half-a-decade. IS was well into a recovery and had significant momentum by mid-2011: the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Iraq and the spiralling of Syria’s uprising into a civil war at the end of the year cleared the way for IS to more fully implement a program that was largely derived from the two shaykhs. Once Fallujah fell in January 2014, the road to the caliphate was open.

ISLAMIC STATE ACKNOWLEDGES THE LOSS OF THE TWO SHAYKHS

Al-Zawi and Al-Badawi were killed near Lake Tharthar, a stone’s throw from Tikrit, the hometown of Saddam Husayn (and Al-Dawr, if it comes to that, where Saddam was captured in December 2003). Some had expected the Islamic State to deny its leaders had been killed, or at least for a time to obfuscate. Instead, ISI put out a statement online confirming the two shaykhs’ deaths on 25 April 2010, a week after they had been killed.

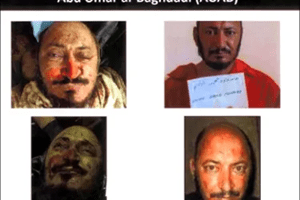

The IS movement is generally honest about these things anyway, but there was not much they could have done even if they wanted to in covering up the two shaykhs being killed because the Iraqi government had released pictures of Al-Zawi (above) and Al-Badawi (below) after death:

The statement was issued under the name of “Abu al-Walid” Abd al-Wahhab al-Mashadani, the ISI “Minister of Shari’a Committees”, a position he had held since the naming of the “second cabinet” in September 2009. (Unfortunately, I cannot find the entire original statement, but the key quotations were reported on at the time.)

Al-Zawi—referred to by Al-Mashadani as “Emir al-Mu’mineen” (Commander of the Faithful)—“had arrived at one of the guesthouses in that area to receive visitors in order to resolve some matters of the State, and attending the meeting was his First Minister, Abu Hamza al-Muhajir.”

“When the attacking force arrived, the security detachment [protecting Al-Zawi and Al-Badawi] engaged them and forced them to withdraw, such that they did not dare enter the area”, Al-Mashadani’s statement went on. “After that, several targets were bombed by aircraft, including the house [where the ISI leaders were holed up], until they confirmed its total destruction and the sure killing of those who were inside.” Al-Mashadani says, and he is probably correct, that the U.S. soldiers were surprised to find “the two shaykhs” (al-shaykhan) were the casualties.

Al-Mashadani addressed the rest of his statement to “the Crusader-Rafidi alliance”, writing that any satisfaction they took from this was illusory because the leaders’ demise would not greatly impact this progress for the ISI: “The two shaykhs and the Shura Council of the State prepared well for this day and made provisions for it and resolved the matter beforehand—and how could they not, when the two shaykhs never went an hour without facing death, with the explosive belt never leaving their sides.”

Al-Mashadani concluded by saying “the mujahideen” had been making strides of late and this progress would continue. “Many of the truthful have joined the ranks of the Islamic State, those with whom discussions had begun before and after the initiative of Shaykh Abu Umar”, wrote Al-Mashadani, who pointed specifically to Jaysh Abu Bakr al-Siddiq al-Salafi (The Salafi Army of Abu Bakr al-Siddiq), which joined “the State of Islam” days after the two shaykhs were eliminated.

Interestingly, there was an audio statement from Ayman al-Zawahiri, Bin Laden’s deputy, on 20 May 2010, lauding Al-Zawi and Al-Badawi on behalf of Al-Qaeda. With plenty of venom towards the “Crusader-Safavid alliance”, Al-Zawahiri praised the two shaykhs for paying “the price of imminent victory”. It seems Al-Zawahiri waited for the ISI to make the formal appointment of the new leader, Ibrahim al-Badri, on 16 May 2010, presumably so that his statement could add to the sense of unperturbed continuity for the ISI.