By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 7 February 2025

The written biographies of the Roman Emperor Elagabalus (r. 218-22 AD) claim that he oversaw an effort to replace the traditional gods with the Syrian sun god of which he was the high priest, and that this was part of the reason he was overthrown. There is, however, no physical evidence for an Elagabalan religious revolution, and we have an idea of the kinds of evidence that should show up where a ruler has tried to impose a new religious dispensation and it has been rejected by his successors because we have counter-examples.

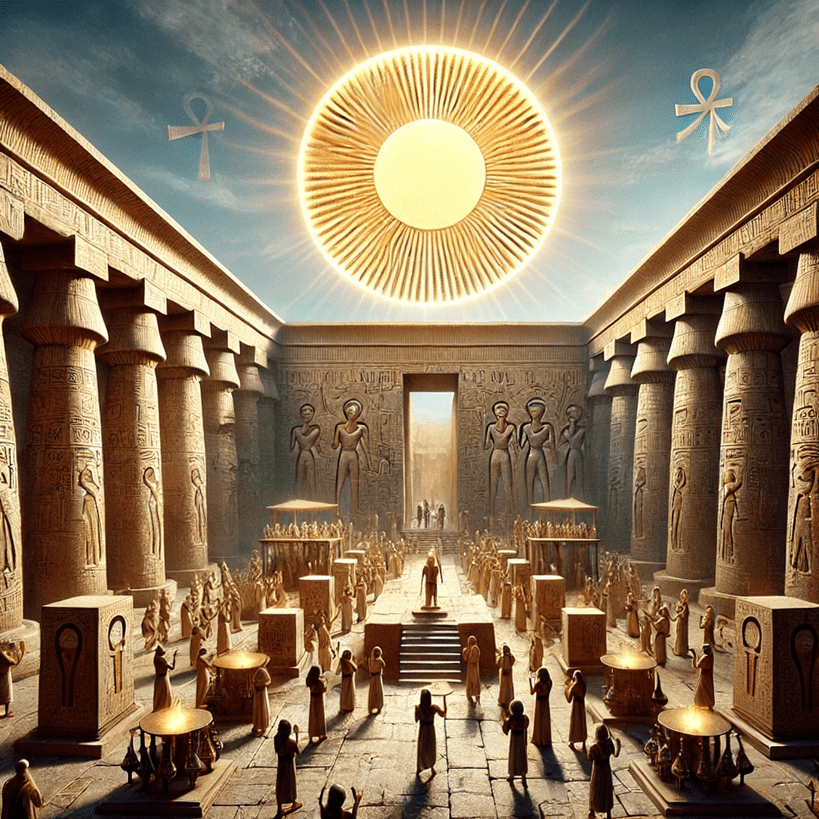

The most famous known case is Akhenaten (r. c. 1353-36 BC), the Pharoah who reordered the Egyptian cosmos around the Aten (lit. “disk”, the sun), in what appears to be the earliest instance of monotheism, or at least the most radical form of henotheism to that point.

Akhenaten founded a whole new capital at what is now Amarna, which was adorned—as the archaeology shows—with a vast open-air temple unlike anything else known in Egypt’s history. The building materials for temples was changed; the inscriptions and decorations at the Royal palaces show unique art and symbols; the change in religious decrees are recorded on stelae; the reliefs of Akhenaten present him in a way seen with no other Egyptian monarch; and the tomb of Akhenaten is not only free of textual or iconographic references to the traditional gods like Osiris and Amun, while extolling the Aten, including in the Great Hymn to the Aten, but the whole architectural style and layout of the burial chamber is different to that of any other Pharoah.

Perhaps most significantly in terms of the evidence left to us, Akhenaten tried to erase the former gods—Amun temples in Thebes and elsewhere were repurposed, for example, and there was an effort to chisel out the name and images of Amun at the Temple of Karnak, which seems to have encountered resistance, leaving helpful traces of what had happened—and there is extensive evidence of a systematic attempt to bury the memory of Atenism.

The physical evidence of the destruction of Atenist temples and inscriptions is dotted all over Egypt, and Akhenaten’s entire capital city was dismantled. Akhenaten’s tomb—desecrated and abandoned—was in Amarna, rather than the Valley of the Kings, and while his son, Tutankhamun (r. c. 1332-23), was buried in the Valley of the Kings, the tomb’s unusual size and position helped alert archaeologists that something was amiss. Related to this is the written evidence of both Akhenaten and Tutankhamen being removed from the King Lists, which, ironically, is part of the explanation for the latter’s tomb being so well-preserved—grave robbers did not know to look for it.

There is also the contemporaneous written evidence alluding to Akhenaten’s Revolution in the form of the “Amarna Letters”, the diplomatic correspondence during Akhenaten’s reign showing Egypt’s neighbours deducing that domestic upheaval is behind the diminished military threat Egypt is posing to them. The records also tell of the shock at Akhenaten’s attack on Amun’s priests, defunding them and otherwise weakening their status.

There is still much debate about the exact nature of Akhenaten’s Revolution, but the convulsion was so enormous that it left copious physical evidence and the religio-social trauma of it reverberates down the ages in the Egyptian records. We see none of this with Elagabalus, and it is inconceivable an Elagabalan religious revolution could have taken place in the context of the Roman Empire—more literate, far larger, 1,500 years later—and left fewer traces. The only possible point of comparison is that Elagabalus was subjected to damnatio memoriae, but that was a common fate for deposed Roman Emperors and has no specific connotation with a posthumous rejection of their divine orientation.