By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 7 February 2025

When Septimius Severus became Roman Emperor in 193 AD, his wife, whom he had married in 187, was Julia Domna, a native of Emesa (now Homs), meaning Rome had its first Syrian Empress.

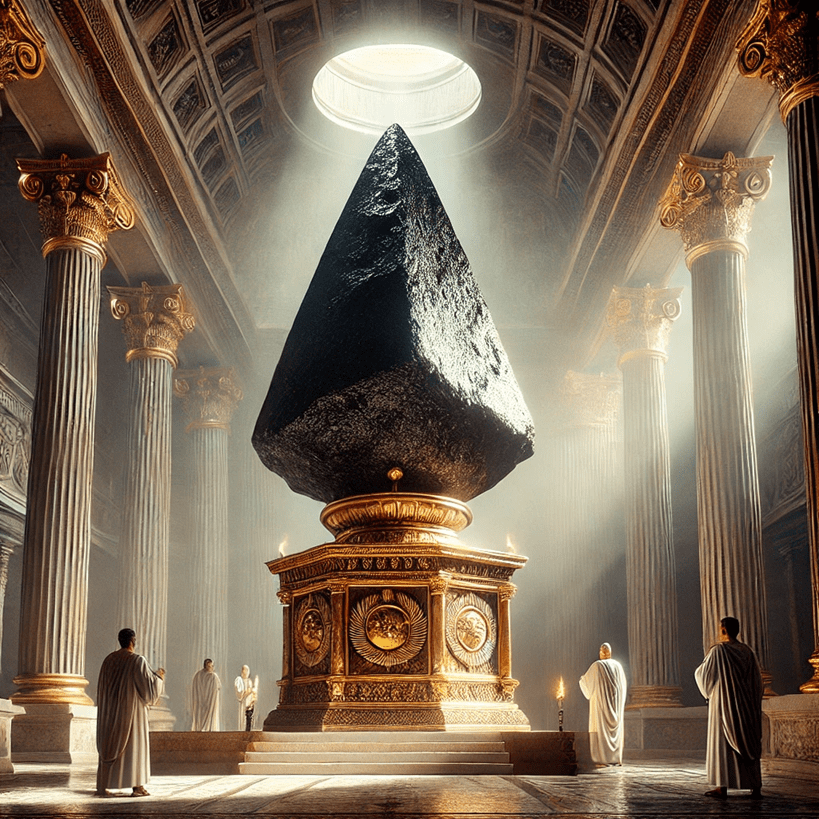

Domna was born c. 170. Her father, Julius Bassianus, was the high priest (pontifex) of the sun god Elagabal (or Heliogabalus), and descended from the Emesene or Sampsigeramid line, the dynasty of Priest-Kings who were clients of Rome from 64 BC, when Pompey Magnus conquered Syria.

Domna and her family are often now described as “Arabs”, but this is clearly mistaken. In the third century, the Arab presence in Syria was minimal, confined largely to the south. Arabs were dominant—as the name suggests—in the Arabian Peninsula. By the sixth century, Arab nomads had spread north of the Peninsula and settled into increasingly sophisticated, Romanised, and Christianised polities, including most notably the Ghassanid Kingdom, an important client-ally of the Byzantines. But all these Arab confederations remained outside the Roman frontier, south and east of what had been Judea, the province renamed Syria Palaestina by Hadrian (r. 117-38) and split into Palaestina Prima and Palaestina Secunda at the end of the fourth century. After the Arab conquests of the seventh century, Damascus became the capital of the Umayyad dynasty, making Syria a particular focus of Arab colonisation, though it still took several centuries for Syria to acquire an Arab majority.

The Romans, who were quite exacting in naming populations, never described Domna’s family as “Arab”: the use of this ethnic label is a modern, anachronistic, and quite politicised imposition. Herodian (5.3.2) describes the family as “Phoenician”, and this is likely to be more correct. “Bassianus” seems to be a Latinised form of the Phoenician word basus, meaning “priest”, for example. Whether the Emesenes were actually descended from Tyre, or from other Semitic peoples in the Levant like the Arameans and Assyrians who had been in Phoenicia’s orbit, we cannot know. Culturally, however, we have more certainty: the Emesenes were a product of the Hellenistic era, speaking Greek, and by the third century were thoroughly Romanised and integrated into the Imperial elite.

The structure of rule established by Pompey lasted about a century. The exact administrative compact in Emesa after the 70s AD is murky.

The records show that Vespasian (r. 69-79 AD) had a close relationship with the Emesenes under King Sohaemus (r. 54-73). Sohaemus, already the custodian of Sophene by a Roman decree, was one of the first to recognise Vespasian as Emperor, and Sohaemus provided support during the Roman assault on Judea. After Sohaemus died, Vespasian evidently tried to bring Emesa under some form of direct Roman rule, and did so in 78 AD, enrolling Emesa as part of Roman Syria. As 78 AD is also the last year when it is certain an Elagabalan priest ruled in Emesa as King—Sohaemus’s son, Gaius Julius Alexion (r. 73-78)—it is entirely possible this was the end of Royal government in Emesa, but there is simply an absence of evidence for the next century.

The records for Emesa pick up again in 187 AD, when Septimius Severus arrives. Severus’s wife had died the previous year, and a horoscope told him he would find another wife in Emesa. (Caracalla inherited this fondness for astrology.) Duly directed to Domna by Bassianus, it is apparent that Severus thereafter took an interest in Emesa and used his marriage connection to establish tight control over the city, which remained a focal point of pilgrimage and tribute to the Temple of Elagabal.

What is unclear is how much, if any, effective autonomy was left for Severus to take away, and when exactly the priests of the Elagabal cult lost their Kingly status because, while it is reasonably certain Julius Bassianus was not a King, the fragmentary records are interpreted by some as showing the Priest-Kings in place in Emesa as late as the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius (r. 138-61).

SOURCES:

Herodian, History of the Empire from the Death of Marcus, written c. 240-50 AD.

Anthony R Birley (1971), Septimius Severus: The African Emperor, chapter eight.

Fergus Millar (1993), The Roman Near East, 31 B.C.-A.D. 337, pp. 302-03.

Barbara Levick (1999), Vespasian, pp. 125-27.

Martijn Icks (2011), The Crimes of Elagabalus: The Life and Legacy of Rome’s Decadent Boy Emperor, p. 50.

Tony Sullivan (2024), The Roman Emperors of Britain, p. 107.