By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 7 November 2022

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 30 December 2021

Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich in exile in France, February 1929

Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich (1866-1933), the brother-in-law of Tsar Nicholas II (r. 1894-1917), gives an interesting anecdote in the second volume of his memoirs, Always a Grand Duke, published in the year he died, 1933, showing how the last Russian Emperor conceived of the duties of his office. Continue reading

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 13 December 2021

Grigori Rasputin

Grigori Rasputin, a Siberian peasant holy man, was a presence at the Russian Court between 1908 and his murder in 1916. Even so, Rasputin would only have been one figure among many and not be so notable in history, except for the fact that he gained significant political influence in his last couple of years due to his friendship with the Tsar’s wife. The degree of influence Rasputin exerted and the stories of his debauched behaviour have often been wildly exaggerated—at the time and since. But the stories did have a basis in fact—the Tsarina had fused together her personal forays in mysticism with her political role—and the stories themselves, lurid and defamatory as many of them were, had a concrete effect in damaging the monarchy as Revolution loomed. Continue reading

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 10 December 2021

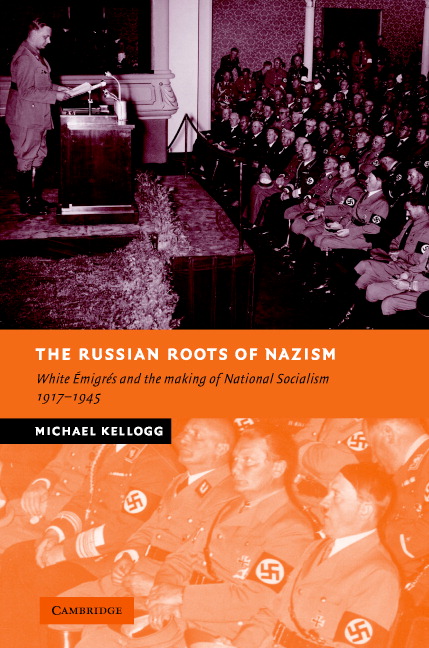

Michael Kellogg’s 2005 book, The Russian Roots of Nazism, argues that Russian “White émigrés” exerted financial, political-military, and ideological influences that “contributed extensively to the making of German National Socialism”. As such, argues Kellogg, Nazism “did not develop merely as a peculiarly German phenomenon”, but within an “international radical right milieu”. The book is interesting but deeply flawed, overstating its case by failing to set the facts it gathers in a proper context and for similar reasons misunderstanding where some of the Russian elements under discussion fit within the politics of the revolutionary upheaval after 1917, both within the borders of Russia and in exile in Europe. Continue reading

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on November 20, 2016

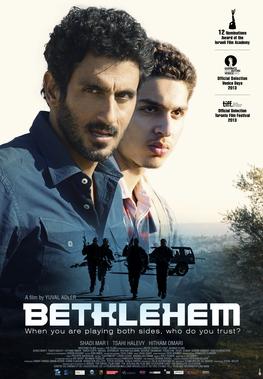

Bethlehem is one of the most compelling films I’ve seen in a long time. There are so few good spy films available that this is a welcome surprise. Unlike Burn After Reading, a genius film, the intention here is not to show things from the agency side, to demonstrate how wildly out of control things can get when you only have half-or-less of the facts. It is also not Charlie Wilson’s War, which shows the feats that intelligence agencies can accomplish when well-directed. Bethlehem is most like Breach, which showed the immense damage an individual spy can do. But instead of showing the effects the act of spying had, with the human characters secondary, Bethlehem tracks specifically the complex relationship that develops between handler and asset. Continue reading

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on August 1, 2015

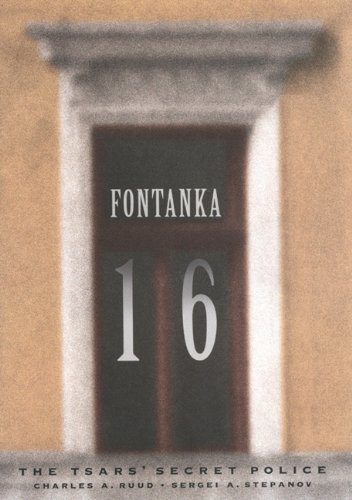

Charles Ruud’s and Sergei Stepanov’s Fontanka 16: The Tsar’s Secret Police traces the evolution of political policing in Russia, focusing on the Okhranka, the final incarnation of the secret police before the Russian Revolution in 1917, and along the way puts paid to a whole array of myths about the pre-Bolshevik Russian government, especially as regards the Jewish Question.

The growth of the Russian political police occurred in four major stages. The first phase lasted from the founding of the Russian State by Ivan the Terrible (1533-84) after the expulsion of the Tatars to the opening of the “Third Section” in 1826 as a reaction to the Decembrist revolt the previous year—the first time the Imperial State security services were housed at Fontanka 16 in St. Petersburg—which intended to (and succeeded in, as 1848 would demonstrate) extirpate the liberal spirit that challenged the autocracy. The third phase saw the Third Section become the Department of Police at the onset of a crackdown after the assassination of Alexander II in 1881, who had enacted broad liberal reforms on censorship and serfdom. The elite secret police force grew out of the palace guard, becoming known as the Okhranka (though this is more usually rendered in English as Okhrana). The final phase began in 1906, after the 1905 revolution, when the Okhranka worked to stop a liberal-radical coalition building. Continue reading