By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on January 25, 2015

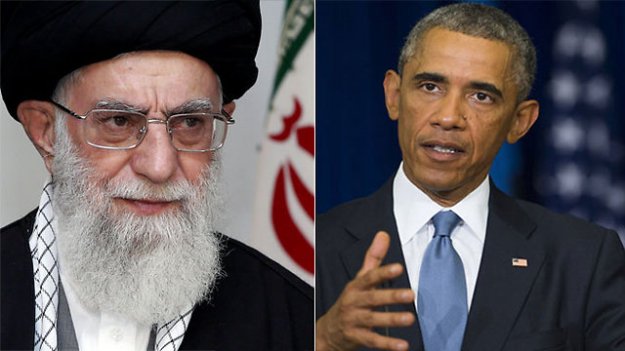

This is the first of a four-part series looking at the United States’ increasingly-evident de facto alliance with Iran in the region. This first part looks at the way this policy has developed since President Obama took office and how it has been applied in Iraq. Part two will look at the policy’s application in Syria; part three will look at its application in Lebanon, Afghanistan, and Yemen; and part four will be a conclusion.

The negotiations over Iran’s nuclear-weapons program ended with an extension of the Joint Plan of Action (JPA), the “interim” deal worked out in November 2013, which now looks effectively permanent, at least while President Obama is in office. That “deal” locked in concessions to Iran that allow the regime to continue to build its infrastructure to make itself a latent nuclear power, and holds out the prospect of a “final” deal with a sunset clause that, once it elapses, would allow Iran to breakout without any constraints.

The nuclear negotiations, however, and the decidedly soft line of the Obama administration in them, are only part of a shift of strategy by the United States to a de facto partnership with Iran, specifically against the Islamic State (I.S.) in Syria and Iraq, but also in Lebanon, Afghanistan, and Yemen. This shift intends to allow the formation of a regional balance of power to replace American hegemony, allowing the Obama administration to complete its long-telegraphed desire of getting the U.S. out of the Middle East.

The premise of a détente with Iran is that Iran, despite the ideological hostility of its leadership to the U.S., has numerous common interests with the United States, first and foremost against Sunni jihadism and in the stability of its Arab neighbours, namely Syria and Iraq, and that Iran has capabilities in these arenas to help the U.S. that traditional U.S. allies like Israel and Saudi Arabia do not. This is catastrophically mistaken, and has led to disaster already.

*****************

President Obama came into office with a clear intention to lower America’s profile in the world, the Middle East specifically. He intended to “end” the Iraq War—to withdraw American troops from Iraq, anyway—and to conciliate foes, namely Clerical Iran and Bashar al-Assad’s Syria. Obama was sure Tehran and Damascus had legitimate demands that could be met by compromise but had been alienated by the cowboy antics of his predecessor. John Kerry, as head of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, was the administration’s point-man in “outreach” to Damascus, and “became Assad’s most important booster in Washington.” The ostensible purpose of this outreach was to explore a “Syria track” to peace in former Mandate Palestine. Assad’s alliance with Iran was a mere “marriage of convenience,” Kerry wrote in 2008 in a joint op-ed with recently-departed Defence Secretary Chuck Hagel, which would be cast aside for the right price—in other words, Assad should be given concessions to break with Iran, rather than being pressured into doing so. Assad had a “strong desire” to be part of an Israeli-Palestinian settlement, Kerry and Hagel wrote, and America should let Assad into that process—accommodating Assad’s interests in yet another theatre—not least because Assad “views peace talks with Israel as part of a broader rapprochement with America”. Thoughts of realigning America’s foreign policy were already alive in the administration at this early stage.

So began a series of trips by Kerry to Damascus, including having dinner with the Assads and saying nothing when Assad was found complicit in a massive bombing in Baghdad in August 2009, which led to the withdrawal of Iraq’s ambassador in Damascus—one of many missed chances to avoid Iraq slipping into the Iranian camp. Kerry retraced the well-worn steps of men like Bill Clinton’s Secretary of State Warren Christopher, who paid twenty-nine visits to Syria, “more than he paid to any member of … NATO.” And with the same result: the House of Assad had every interest in the peace process, and no interest in actual peace. As Bernard Lewis once succinctly explained it, “As long as there is no peace … Assad is an Arab statesman. If there is peace, he becomes an Alawi tyrant.”

The Assad regime’s legitimacy rested on three pillars: providing stability, recovering the Golan, and the Palestinian cause. For decades the Assad regime fed the population anti-Zionism to deflect from its lack of respect for human rights and its dreadful economic mismanagement. To normalise relations with Israel would be the end of Assad’s regime, so instead Assad sought to protract the problem by sponsoring chaos and terrorism in Palestine and among the Palestinians, especially in Lebanon, and then seeking concessions to stop the problems he had caused. The Assad regime was for decades “at once an arsonist and a fireman,” as Fouad Ajami once put it, and it worked. Hafez al-Assad was allowed to complete the conquest of Lebanon in 1990-91 on an understanding with the George H.W. Bush administration: Assad lent a detachment of Syrian troops to give Arab cover to the operation to get Saddam Hussein out of Kuwait, and Bush’s advisers believed Assad would cap, rather than cause, the mayhem in Lebanon. Syria’s schools taught the young an unremitting antisemitism, that the fight with Israel was “a conflict for existence, not for borders,” and Assad’s capital was the headquarters for innumerable anti-Israel terrorist groups, including Islamists like HAMAS, yet Assad was believed to be able to turn on a dime—and to want to—to end the conflict that was the mainstay of his legitimacy.

Damascus and Tehran had provided the lifeline to the Hizballah, the Iranian revolution’s only true Arab offspring in Lebanon, “the Mediterranean branch of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps“. Where Hafez al-Assad had kept on an even-footing with Iran, since Bashar took office in 2000, Syria “slipped into a relationship of some subservience” with Iran, which has now been completed, with Iran becoming a de facto occupation force in the regime-held areas of Syria.

John Kerry was quicker than most to realise that he needed to step away from his pro-Basharism. In the summer of 2011, Kerry wrote to the Wall Street Journal that he had never “believed or asserted” that Assad was a reformer, and Assad had now “earned our condemnation” with “actions [that] may well result in the end of his reign”. By then, however, it was rather too late: the policy of conciliating the Iranian “Resistance Axis” was already embedded; the Obama administration had stayed silent as the Iranian uprising was crushed in 2009, waiting only for a “decent interval” before re-engaging the regime, and the U.S. administration had called off all attempts to bring about a change of regime in Syria.

*****************

President Obama began airstrikes in Iraq against the Islamic State on August 7, 2014, and then extended the strikes into Syria on September 23, also targeting al-Qaeda’s local branch, Jabhat an-Nusra and specifically its external operations unit, the so-called “Khorasan Group“. In his Nov. 23 interview with George Stephanopoulos on ABC, President Obama gave a hint about how he sees Iran in this fight. After acknowledging that there were still “problems” with Iran “in terms of their attitude towards friends like Israel” and “sponsoring” terrorism, nonetheless, said Obama:

“What a [nuclear] deal would do is take a big piece of business off the table and perhaps begin a long process in which the relationship not just between Iran and us but the relationship between Iran and the world, and the region begins to change.”

In short, the Obama administration has narrowed the problems with Iran to the sole question of nuclear weapons, and even then only an actual breakout—not capacity, which is what worries America’s allies—and sees Iran as an ally against (Sunni) terrorism, Iran’s own status as the leading State-sponsor of terrorism notwithstanding. Where once Iran presented multiple problems—internal repression, regional subversion, global terrorism, and a desire to back all these things up with the strategic ambiguity that comes with the possession of nuclear weaponry—now the U.S. administration defines the problem as one solely of numbers, not the existence of (as has been the policy until now), centrifuges, and the stockpile of enriched uranium, a meaningless thing if the capacity to enrich more is left in the hands of Iran.

This narrowing of the Iran Problem has been supported with an argument, focussed on Iran’s president Hassan Rowhani, that Iran is undergoing a strategic shift, with moderates in the ascendancy and the desire for more normal relations with the United States. In fact, this strategic shift has been wholly on the American side. Sunni jihadism has been elevated to the primary problem of regional order, which can make Iran seem like a nasty-if-necessary ally, and the price the Obama administration has willingly paid for this shift is all-but abandoning the containment of Iran’s expansionism, and the ultimate downfall of the Islamic Republic, as a U.S. goal. Put simply, the Obama administration believes the Islamic State and al-Qaeda are greater threats than Iran. This priority is wildly mistaken—not least because Iran uses the Islamic State and al-Qaeda as tools of its State policy, and has done for nearly two decades.

The Islamic State, even as it evolves from a terrorist network toward a quasi-State with reach into Europe and America via fighters with Western passports, is not as threatening as Iran. Iran’s global terrorist network has hit the West—and world Jewry—far more often than the I.S.’s has, as we were reminded again this week with the assassination of Alberto Nisman. Iran hates the West at least as much as the I.S. does. Iran, like I.S., wishes to erase the State boundaries in the region, and unlike the I.S., Iran has the resources of one of the largest oil-producing States in the world, as well as a sophisticated military-intelligence apparatus, to put that goal into operation. Where the I.S. has reached the outer limits of its Takfiri Caliphate—it cannot go beyond the Sunni Arab zones in Iraq and the best it can do in Syria is to move back into Aleppo and Idlib—Iran has the resources, capability, and will to work across sectarian lines to increase its power and damage the West.

*****************

In Iraq, the Sunni Arabs had been enraged by an increasingly authoritarian and sectarian government, led by Nouri al-Maliki, who has been “a pawn of Iranian intelligence for over three decades“. Maliki had shown these tendencies since he came to power in 2006, but they became especially evident—and unrestrained—after the U.S. troops were withdrawn from Iraq in December 2011.

The U.S. troop withdrawal also lifted the pressure on the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI), the forerunner of what is now the Islamic State (and was ISIS between April 2013 and June 2014). Between July 2012 and July 2013, the I.S. undertook a campaign called “Breaking the Walls” that used massive waves of suicide attacks to stoke the sectarian tensions that were already building because of the Maliki government’s efforts to marginalise the Sunni Arabs. By heightening sectarian passions, I.S. hoped to empower the most extreme forces on the Shi’ite side and goad them into atrocities against Sunni Arab civilians, which would demonstrate that the State could not and would not protect Sunnis, supplying more recruits for the I.S., and these recruits were buttressed by breaking out the I.S.’s veterans from Iraqi prisons. The follow-on “Soldiers’ Harvest” campaign, announced July 30, 2013, was focussed on Mosul, specifically on discrediting the security forces, which are mostly from outside Ninawa Province, to drive a wedge between the State’s security forces and the nominal State agents like Sahwa and judges, who are locals, with assassinations that have them switch sides. In Mosul, the I.S.’s intimidation and assassinations, enabled by the recruitment of locals to strengthen its intelligence capacity, and its racketeering, meant that by 2014, the I.S. was “a shadow authority capable of exerting covert influence by day, and sometimes almost overt control by night.” This was the state of play when the I.S. overran Mosul in June 2014 in less than twenty-four hours with just 1,000 of their own men, despite the presence of 30,000 soldiers and policemen.

As the I.S. was gaining strength, it was being assisted by the Maliki government witch-hunting Sunni Arabs out of all positions of influence and Baghdad’s responding to a Sunni Arab protest movement that erupted in December 2012, and the spillover of unrest from Syria, with heavy-handed, indiscriminate, and ineffective means. The Sunni Arabs seemed to have no peaceful avenues left, and the Sunni population was “teetering on the edge of an uprising as of August 2013“. A full-fledged insurgency was underway by the time the Islamic State raised its banner over Fallujah in January 2014 and Iran’s allies in Baghdad began raining barrel bombs on hospitals in Anbar. The fall of Mosul inflamed this Sunni revolt. Trapped between the Islamic State and the Islamic Republic, the Iraqi Sunni Arabs picked the former. One Iraqi Sunni insurgent said: “After the liberation of Baghdad [from the Shi’a-led government] the Islamic State will be finished. The Sunni rebels are only using them”. This is surely the view of many Sunni Arabs, who have turned on the I.S. before and will do so again once they have used them to damage the central government that has been persecuting them, but it still makes the I.S. the vanguard of a Sunni uprising in Iraq, and traps the Iraqi people in a terrible war between Salafi jihadists and Khomeini’ist jihadists.

It did not have to come to this. When President Obama took office in January 2009, something awfully close to victory had been achieved in Iraq. Violence had fallen and there was a modest sense of optimism among the population. The Surge had created a political space and opportunity, but this required continued, intense American engagement, mostly diplomatic, to ensure that the Shi’a-led government, the Sunni Arab tribes, and the Kurds felt secure in relation to one-another, and to ensure that the nearly-destroyed then-ISI stayed that way. Obama refused to supply this pressure. Indeed Iraq was ignored to such an extent that the point-men in Washington were oblivious to the actual goings-on in Baghdad, even to the most obvious things like Maliki consolidating an autocracy.

Obama then completely abandoned Iraq at the end of 2011. The Obama administration was ostensibly negotiating a Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) to keep U.S. troops in Iraq beyond 2011, yet Obama was told by his military that 16,000 was the minimum needed to buffer the sects and keep ISI down and Obama offered the Iraqi government 5,000 troops, a force barely able to defend itself, an offer that was meant to be refused. Obama then latched onto a legalism about troop immunity from Iraqi courts, and America’s security gains in Iraq and the progress toward democracy were liquidated.

This withdrawal was not just reckless but cynical. The driving force was Obama’s determination to keep to his campaign pledge of getting out of Iraq, one part of pulling back in the Middle East more generally. We know the legalism was cynical because U.S. troops are back in Iraq now under the offer refused in 2011. We also have the word of the President’s team, who said the failure to negotiate a SOFA was “not a setback … because the White House never considered it a requirement.” Ben Rhodes, one of the “gate-keepers” to what even supporters admit is an insular White House, said as late as April 2014 that “a full withdrawal was the right decision“. Obama made use of this decision at the 2012 convention, saying: “I promised to end the war in Iraq. We did.” Of course the war had not ended; indeed a war that had practically ended was restarting. But Obama’s aides had an answer for that too: “If our policy succeeds, we’ll take credit for it. If … Iraq descends into civil war again, we’ll just blame George W. Bush.”

*****************

In re-engaging in Iraq in early August, it made sense to use force to prevent genocide by the Islamic State (I.S.) against the Yazidis and to protect the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), the freedom and prosperity of which is the greatest success of the Iraq invasion. But even for hawks there were grave doubts about a re-engagement in Arab Iraq, since striking at the I.S. there would make the U.S. the air force of a government that was an Iranian satellite, and whose authoritarianism and anti-Sunni sectarianism was a major cause of the crisis to begin with. Syria was important in the I.S.’s ability to invade Iraq in June, but the passive support of Sunni Arabs on which the I.S. relied for its conquest was only present because of the Maliki government’s behaviour. This was an indigenous Iraqi crisis, not merely the end-point of a mistaken belief that Syria’s crisis could be quarantined.

Soon after the U.S. airstrikes in Iraq against the Islamic State began it was confirmed that the U.S. was acting in alliance with Iran to defend an Iraqi government loyal to Iran. “Iran got the West and Sunnis to fight its fight,” and then amazingly extracted concessions from the U.S. in the nuclear negotiations as tribute for allowing the U.S. to fight its fight.

At the end of August, with the help of U.S. air cover, what was left of the Iraqi Army and Iranian proxy “paramilitary forces” gathered under the banner of the Hashd al-Shabi, including the Imam Ali Brigade (IAB) and Asaib Ahl al-Haq (AAH), pushed the I.S. out of Amerli, a Shi’a Turcoman town in northern Iraq. After they conquered Amerli, IAB engaged in savage conduct, wholly indistinguishable from the Islamic State, beheading unarmed prisoners and celebrating it on video. IAB is a wholly owned subsidiary of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corp (IRGC), as is AAH, which was the most dangerous anti-Western Shi’ite group in Iraq during the American regency, murdering hundreds of American and British soldiers.

Just before Amerli, Iran had put troops across the Iraqi border into Jalawla, Diyala Province, to fight alongside the Peshmerga, seen by most as the West’s most reliable on-the-ground ally. The pictures later of Qassem Suleimani, the commander of the Quds Force, the foreign action wing of the IRGC, charged with exporting the Islamic revolution, in the company of the Peshmerga were clearly meant to say to the West that Iran was ubiquitous; that to do anything in the region, the U.S. needed Iran’s help. (It was also for local purposes: to shift credit away from Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, whose fatwa on June 13 triggered a mass-mobilisation of Shi’ites to fight the I.S.)

There were Shi’ite militias alongside official Iraqi forces when I.S. was driven from Jurf al-Sakhar in Babil Province in late October with the help of “heavy coalition air strikes,” and U.S. airstrikes were key in breaking the I.S.’s hold on Baiji, a town with a major oil refinery in Baghdad. Even when the headline of news stories was that there had been Sunni Arab tribal help for the Shi’a-led Iraqi government’s armed forces, supported by U.S. airstrikes, in al-Anbar against the Islamic State, it turned out there had been a “need to call in some 3,000 Iranian-backed Shiite militiamen,” so ramshackle a condition is the Iraqi Army in and so pervasive is Iran’s presence in Mesopotamia.

For reasons unclear, Iran’s Shi’a proxy jihadists do not seem to have the same connotations of pure horror in the West that al-Qaeda and the Islamic State do. But these militias behave every bit as cruelly as al-Qaeda and the I.S. (255 Sunni civilians were slaughtered over less than two weeks in June as Iran’s militias swept across central Iraq, an incident of war-crimes-bordering-on-ethnic-cleansing); are every bit as fanatical (“Suleimani has taught us that death is the beginning of life, not the end of life“), and they have the backing of an oil-rich State and a global intelligence service. They also started this cycle of sectarian killings.

An excellent article in the Wall Street Journal on Dec. 5 noted that politicians in Baghdad were already referring to Iran’s proxies as “Shi’ite Islamic State”. The group that drove I.S. out of Jurf al-Sakhar is run by Ahmed az-Zamili, who was recruited by the Hizballah in Lebanon, where he learned to desire to “sacrifice myself for the sake of God and religion” at training camps. On return to Iraq, Zamili worked closely with Qais al-Khazali, AAH’s commander and another Iranian agent, and he has been for further training in Iran before waging jihad in Syria, the site of the first multinational Shi’a jihad akin to the Sunnis’ Afghanistan, Bosnia, or Chechnya in the 1980s and 1990s. Zamili’s group is called al-Qara’a (Judgment Day) and fought alongside Kataib Hizballah, a U.S.-designated terrorist group, in Jurf al-Sakhar. Zamili’s group openly admits murdering Sunni POWs, and at one stage “Al Qara’a members hurried out of a meeting with a reporter for The Wall Street Journal to deliver the severed head of an Islamic State fighter to relatives of a slain militia member before his funeral ended.” Senior Shi’ite politicians worry that in the chaos Iran is creating “Shi’a al-Qaeda,” and with good reason.

*****************

After repeatedly denying that there would be any co-ordination with Iran, despite repeated reports that the U.S. was co-ordinating with Iran’s proxies in Iraq using the Iraqi military as an intermediary, the Obama administration first leaked to sympathetic columnists at the beginning of September that it had “opened a quiet back channel to Iran to ‘deconflict’ potential clashes” as both Iran and the U.S. battled the I.S., and then it was admitted outright that there were “occasional back-channel conversation on this topic” in mid-September. In late November 2014, Iran sent its own fighter jets into Iraq to bomb the Islamic State, something it is inconceivable that Iran would do without some kind of foreknowledge of the U.S.—and what is this if not tactical co-ordination? (There are claims that co-ordination was “full“.) Iran lacks the capacity, even if it had the will, for air attacks that don’t kill large numbers of Sunni civilians, and Sunnis can only now conclude these attacks have U.S. sanction. John Kerry said as much: Iran’s actions were a “positive” development, Kerry said, before adding that this was “not something that we’re coordinating.” As I have previously noted, “the Obama administration rhetorically holds up the ‘We Will Not Cooperate With Iran’ line like an amulet, while on the ground the evidence to the contrary mounts up.” As even the New York Times noted, “The Obama administration has made clear that … it welcomes Iran’s help in fighting [the Islamic State]”. Moreover, Obama’s pledge to destroy the Islamic State by “working with the Iraqi government” is an announcement of co-operation with Iran. Iran is in effective command of the Iraqi government’s military, as was underlined at the end of December, when Iran and Iraq signed a security agreement under which Tehran will continue to train units of the Iraqi military. Obama professed to believe that replacing Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki with Haider al-Abadi created an “inclusive” government in Baghdad. This was blatantly untrue: Abadi was an “Iranian victory”. As just one example, Abadi was “determined” to appoint Hadi al-Amiri as Interior Minister, the part of the Iraqi State officially dealing with the “volunteer” Shi’ite militias fighting alongside the army, many of which have been co-opted by Iran even though they were initially responding to Sistani’s fatwa. Amiri is a long-time agent of Iran and leader of the Badr Brigade from which many of Iran’s other proxy groups in Iraq and Syria originate. Eventually a fig-leaf candidate was chosen but Amiri and Iran retain their control of this key institution of the Iraqi State. Anything passed to Baghdad goes to Tehran—and everyone knows it.

One Iranian official claimed that Iraq was “very similar to what happened in Bosnia,” where “Iran supported the Muslims … while the United States showed verbal support.” Now in Iraq, Iranians “are the ones fighting on the ground … while the airstrikes by the United States and its allies materialized nothing on the ground.” This is a large degree of truth to this: up until the major NATO air campaign after Srebrenica, the U.S. had rhetorically supported the Bosnian Muslims while allowing Iran to do the work on the ground, bringing in more than $200 million-worth of war material, including fourteen thousand tons of weapons, and embedding its intelligence apparatus in the Bosnian State. That attempt at co-operation with Iran ended with an Iranian attempt to assassinate the CIA station chief in Sarajevo in 1995.

The only thing America appears to have gotten out of this partnership with Iran in Iraq is that in early October, the Supreme Leader told Iran’s proxies in Iraq to lay off American troops while they were being Iran’s de facto air force. It seems however that this was contingent on that support continuing: now U.S. officials see U.S. troops, and even Embassy staff, inside Iraq as hostages, who could be targeted if the U.S. did anything to check Iran’s imperial ambitions in the Fertile Crescent. (Obama has done this before: when he put troops in Kuwait, supposedly to contain Iran, they were then used to blackmail Israel that if she did anything to disarm Iran, U.S. troops could be attacked. Instead of a tripwire, the U.S. troops were made willing hostages.) In this case Iran need not have worried. As Hisham Melhem reported, John Kerry had “asked for a review of options … but cautioned that the options should not include anything that would upset Iran and could conceivably have a negative impact on the nuclear negotiations with Tehran or its long-term strategic interests,” and while this was true for Iraq, Kerry was particularly adamant that nothing should be done to upset Iran in Syria.

*****************

Pingback: America’s Silent Partnership With Iran And The Contest For Middle Eastern Order: Part Two | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: America’s Silent Partnership With Iran And The Contest For Middle Eastern Order: Part Three | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: America’s Silent Partnership With Iran And The Contest For Middle Eastern Order: Part Four | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Shi’a Holy War and Iran’s Jihadist Empire | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Obama’s National Security Strategy | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Islamic State, Libya, and Interventionism | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Obama’s Syria Policy Protects Assad | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Iran and Global Terror: From Argentina to the Fertile Crescent | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Allowing Iran To Conquer Iraq Will Not Help Defeat The Islamic State | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Netanyahu Spoke The Truth About Iran At Congress | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Amerli Shows The Futility Of Aligning With Iran To Defeat The Islamic State | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Netanyahu Spoke The Truth About Iran At Congress | The Office of Robbie Travers

Pingback: A Red Line For Iran’s Imperialism In Yemen | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Local And Regional Implications From The Fall Of Idlib | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Why The West Should Support The Saudi-Led Intervention In Yemen | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Obama’s Iran Deal Increases Nukes, Terrorism, and Instability | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Book Review: The Consequences of Syria (2014) by Lee Smith | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Raids in Syria Can’t Defeat the Islamic State If Obama Continues Alignment with Iran | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Islamic State’s Strategy Is Working, Its Enemies Are Failing | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Nukes and Empire: The West is on the Brink of Giving Iran Everything it Wants | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Islamic State: The Afterlife of Saddam Hussein’s Regime | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Everything You Need to Know About Trump’s Iran Deal Decertification – The Sundial Press

Pingback: Everything You Need To Know About Trump's Iran Deal Decertification - Le Zadig

Pingback: Trump Completes Obama’s Syria Policy / Kyle Orton's Blog

Pingback: Obama's Iran Deal Increases Nukes, Terrorism, and Instability | Kyle Orton's Blog