By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on March 7, 2015

Earlier this week I wrote of the unmasking of “Jihadi John,” the Islamic State’s (ISIS) video-beheader, as 26-year-old British citizen Mohammed Emwazi. I had two purposes. One was to gloat over the implosion of CAGE (formerly Cageprisoners), an Islamist terrorist-advocacy group that had gotten itself called a “human rights organisation”. And the second was to point out that the narrative peddled by CAGE and other apologists, that Emwazi had been radicalised by heavy-handed British security methods, was plainly absurd.

Emwazi had been associating with al-Qaeda agents and sympathisers and was part of a London-based network that dispatched fighters to al-Qaeda’s Somali branch al-Shabab years before he came into contact with the security services—indeed the security services had only taken an interest in Emwazi because he was already radicalised. In the last few days both of these trends have continued: CAGE’s total collapse moves closer and Emwazi’s known nefarious associations are multiplying.

******************************************************

On Feb. 26, the day Emwazi’s identity was publicly revealed, Asim Qureshi, variously described as CAGE’s “research director” and “executive director,” gave an hour-long press conference to explain away the fact that Emwazi had had a three year association with CAGE between the summer of 2009 and January 2012. I described the press conference as a “protracted hara-kiri” because Qureshi’s performance, presenting Emwazi as the victim, inspired such revulsion that finally CAGE’s nature was widely understood.

On March 5, Qureshi appeared on This Week with Andrew Neil. Qureshi was asked about Haitham al-Haddad, an extremist preacher whom Qureshi has chosen as his spiritual mentor. Evasive as ever, Qureshi was then asked to condemn, in principle, the stoning to death of women for adultery. He would not. Qureshi was asked to explain his call for jihad against the West in 2006, and his association with Hizb-ut-Tahrir (HUT). Qureshi said that the audience would have understood that, in calling for jihad, Qureshi and CAGE “do not advocate terrorism,” and excused HUT not only as “non-violent” (for which a case can be made) but “not an extremist organisation” (which is a flat-out lie).

Yesterday, the Roddick Foundation, which has paid CAGE £120,000 between 2009 and 2012, and The Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust (JRCT), which has given CAGE £270,000 between 2007 and 2014, announced that they have ceased funding CAGE and will not be doing so in future. This came after revelations that in July 2013 the Community Security Trust (CST) told JRCT that CAGE had links with one of al-Qaeda’s most important clerics, Abu Qatada al-Filistini, and articles on CAGE’s website said that 9/11 was an insurance scam by a Zionist billionaire.

The tabloids are also having a field day. The latest is the exposure of Qureshi’s opulent personal living arrangements—a £700,000 house in Surrey on “a tree-lined avenue in immaculate contoured grounds that include tennis courts, nature trails and cycle paths,” apparently.

In public relations, then, and funding opportunities from credible organisations, CAGE is finished. The infrastructure that sustained CAGE is largely still intact, and there will be future groups that cover their Salafi jihadism with a public “moderation,” and the respectable will be desperate to believe it. But this one group is at an end, and in future the example of CAGE will make it less easy to dismiss those who ask whether a Muslim advocacy group is actually moderate as “Islamophobes” and the rest of it.

******************************************************

Bilal el-Berjawi was a Londoner of Lebanese extraction, who had also “interacted with CAGE“. Berjawi trained in Somalia in late 2006 and returned to Britain in early 2007. With Walla Eldin Abdel Rahman and Mohammed Sakr, a friend of Emwazi’s since childhood, Berjawi had travelled to Somalia by November 2009 to fight for al-Shabab. These men claimed, as Emwazi later would when he tried to get to Somalia via Tanzania, that they were going on “safari”. Berjawi was killed by an American drone strike in January 2012, and Sakr was killed the same way the next month. Court documents showed that Emwazi had a “close association with these radicals“.

CAGE’s entire story about Emwazi’s attempted “safari” in May 2009 has fallen apart. CAGE insisted MI5, unprovoked, had blocked Emwazi from entering Tanzania and set him on the path to radicalism. In fact, London had nothing to do with it. Emwazi and the two men he was travelling with—Ali Adorus, 27, an east Londoner who is now in jail in Ethiopia for terrorism offences, and Marcel Schrodl, a 23-year-old German national—were turned back because they were “very drunk” and were “insulting [Tanzania’s] immigration staff and … failed to explain why they had come to Tanzania”. The 9/11 death pilots are said to have had a final blow-out with drink and hookers the night before their suicide-massacre; when on god’s work it pays to fit in with the infidels, is the logic used to justify this. It does, however, take away some of the mystique around Emwazi to find that his first effort at jihad was blocked by a ten-hour bender.

It is now thought possible that Berjawi knew the men who attempted to bomb London on July 21, 2005, at least indirectly through a Christian convert to Islam known in Islamist circles as Abdul Shakur, who had contacted the would-be bomber Hussain Osman. And at least one report says that Emwazi came into contact with this network at age 18, which is to say in 2006.

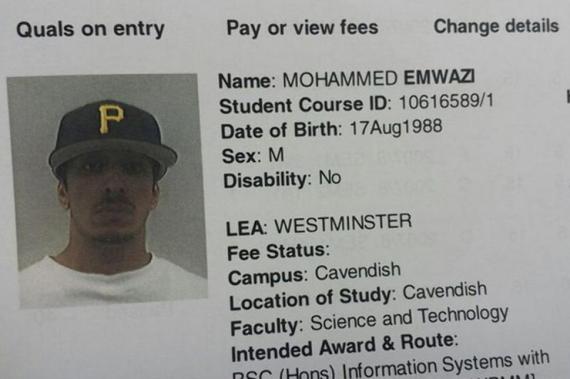

Emwazi attended Westminster University between September 2006 and September 2009, studying information systems and business management. At least two former students have testified to the free rein Islamic radicalism was given on campus, with disdain for homosexuals, Jews, and Christians commonplace, undisguised, and unpunished. Both former students said they were unsurprised somebody who passed through this environment turned to Islamic militancy. As far back as April 2011, the links between student union president, Tarik Mahri, and his deputy, Jamal Achchi, and Hizb-ut Tahrir, were a matter of public record.

Whether Emwazi had radical associations at University, his connections with radicals go back to his high school, the Quintin Kynaston academy in north-west London. Sakr was also a pupil at Quintin Kynaston, an exact contemporary. And another pupil, Choukri Ellekhlifi, two years below Emwazi and Sakr, had been a part of Berjawi’s network and was killed fighting for al-Qaeda’s Syrian branch, Jabhat an-Nusra, inside Syria on Aug. 11, 2013. Ellekhlifi, a Briton of Moroccan descent, had been a petty criminal who used a stun gun for a string of robberies in Belgravia. Despite the age difference, Emwazi was close to Ellekhlifi as well: “They lived in the same area and they were friends all the way through school … they went to mosque together”.

The Berjawi network was also known as “The London Boys”. Berjawi lived in the St John’s Wood area of London, a few miles away from Emwazi. Berjawi had been in Somalia in 2006 before returning to Britain to raise funds—and recruits—in 2007.

Another member of “The London Boys” is Reza Afsharzadegan. Of Iranian descent, Afsharzadegan came to Britain as a young man and settled in Ladbroke Grove, west London. Afsharzadegan studied IT. Afsharzadegan had twice tried to get to Yemen, though when is not exactly clear. It seems to be in the first half of 2006. Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) was officially founded in January 2009 but AQAP’s precursors had been greatly strengthened in the wake of the 2003 crackdown in Saudi Arabia that drove much of al-Qaeda’s infrastructure from al-Saud into Yemen.

By the fall of 2006, Afsharzadegan and three other British men—Mohammed Ezzouek, Hamza Chentouf, and Shahajan Janjua—were in Somalia training with Fazul Abdullah Mohammed (a.k.a. Harun Fazul), the leader of al-Qaeda’s presence in East Africa, who was at least in Mogadishu during the “Black Hawk down” episode in October 1993 and participated in the conspiracy to bomb the American Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in August 1998. Fazul was killed on June 8, 2011, after refusing to heed instructions at a Kenyan military checkpoint.

According to leaked Joint Task Force Guantanamo (JTF-GTMO) threat assessment files, at least “eight foreigners” were present in late 2006 when Fazul taught “a six-week advanced training course on forging documents, manufacturing passports, and conducting surveillance using covert photography”. JTF-GTMO also identifies Fazul as “a bomb expert”.

In 2011, the British Home Office gave an assessment of who was part of “The London Boys” network: “BX, J1, Mohammed Ezzouek, Hamza Chentouf, Mohammed Emwazi, Mohammed Mekki, Mohammed Miah, Ahmed Hagi, Amin Addala, Aydarus Elmi, Sammy Al-Nagheeb, Bilal Berjawi and others.” The British government believes that someone it names only as “CE” (in reality Afsharzadegan; see below), Berjawi, BX, Ezzouek, Miah, and Chentouf attended Fazul’s course. BX is Ibrahim Magag (see below). (J1 is the above-mentioned Abdul Shakur; his real name remains unknown.)

Afsharzadegan, Ezzouek, Chentouf, and Janjua were returned to Britain on Feb. 13, 2007, in an extraordinary decision by the British Foreign Office. The four men had been arrested in Kenya as they tried to flee Somalia after the U.S. ordered airstrikes against Islamists in Somalia following the fall of Mogadishu on Dec. 28, 2006, to the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), a splinter group of which would become al-Shabab. The foursome were handed by Nairobi to the government, such as it is, of Somalia, which would likely have executed them. Instead, at considerable taxpayer expense, these four known Salafi jihadist terrorists were picked up at the Somalia-Kenya border by the British, quite possibly the SAS, and—after an eight-hour interrogation—turned loose on the streets of London.

Also on Feb. 13, 2007, Kenya arrested Abdulmalik Mohammed (a.k.a. Abdul Malik; a.k.a. Mohammed Abdulmalik; a.k.a. Abdul Malik Bajabu). Abdulmalik confessed to a role in the November 2002 bombing of the Israeli-owned Paradise Hotel in Mombasa, and the follow-on attempt to shoot down an Israeli plane. Abdulmalik was a close associate of Fazul’s. In October 2006, Abdulmalik and Fazul met with an al-Qaeda operative, Saleh Ali Saleh Nabhan, at Abdulmalik’s home where they “discussed potential attacks on U.S. and Israeli Embassies.” Nabhan seems to have helped Fazul run the training camp in Somalia in late 2006, and Fazul, Abdulmalik, and Nabhan were known to other holy warriors as the “Three Musketeers“. The connection of “The London Boys” to Fazul suggests they were closely bound to al-Qaeda’s global terrorist infrastructure.

This closeness of “The London Boys” to al-Qaeda “central” (AQC) or “senior leadership” (AQSL) is underlined by records from Guantanamo Bay, seen by The Daily Mail, which show that Afsharzadegan and his three colleagues, who had been trained by Fazul, were sent back to Britain as “sleeper operatives” at the behest of Osama bin Laden.

A 2011 court case challenging a control order sheds some light on what happened once these men got back to Britain.

Details emerged of Ibrahim Magag, a Somali-born former train conductor from London, who was described as being part of Emwazi’s terrorist cell in London. Magag had been placed on a control order to stop him fleeing oversees, which did not do a lot of good since he left for Somalia on Dec. 26, 2012. While in London, Magag had been involved in arranging “financial support for al-Qaeda”.

The court case had directly related to somebody identified only as “CE,” who was “prevented from attending prayers at a named community centre and banned from using the internet at home”. Biographical details of “CE” include that he was “an Iranian” and that he had “along with Mohammed Ezzouek and Hamza Chentouf … attended the Al Qaeda camp in Somalia led by Harun Fazul”. This makes it almost certain that “CE” is actually Reza Afsharzadegan.

CE/Afsharzadegan lost the appeal. While in London after his return in early 2007, CE/Afsharzadegan “continued to associate regularly” with the Shabab network in London, according to CNN, and was “involved in the provision of funds and equipment to Somalia for terrorism-related purposes and the facilitation of individuals’ travel from the United Kingdom to Somalia to undertake terrorism-related activity.” CE/Afsharzadegan was also “tasked with recruiting others to join Al Qaeda and … Al Shabaab“. Whether CE/Afsharzadegan was responsible for recruiting Emwazi it is not possible to say, but the two men did know one-another: “Emwazi attended two meetings in February 2010 at CE’s West London flat where they were accused of discussing ‘Islamic extremist activity’.” (Notice: “CE” lives in west London. Afsharzadegan lived in Ladbroke Grove.) Indeed, Emwazi (and Mekki) were said to visit CE/Afsharzadegan “often“.

One reason why it might not have been CE/Afsharzadegan who drew Emwazi into radicalisation is that Emwazi might not have been radicalised in London at all. The Telegraph has reported that Emwazi had been converted from Shi’ism to a radical Sunnism in Kuwait in 2007 by Muhsin al-Fadhli, the apparent leader of the so-called Khorasan Group within al-Qaeda in Syria. Emwazi is also said to have met Khalid ad-Dossary, a Saudi national arrested in the U.S. in February 2011 and later sentenced to life in prison for planning to bomb targets that apparently included George W. Bush’s home in Texas.

That Emwazi was at one time a Shi’a is conceivable. His family are bidoon, a stateless (and somewhat persecuted) people on Kuwaiti territory. The bidoon originate among the Iraqi Bedouin tribes and the majority of them are Shi’a.

If Emwazi was radicalised by Fadhli, it would emphasise the fact that Emwazi was moving in circles closely connected with AQC long before the security services paid him any attention.

******************************************************

There is clear evidence that members of “The London Boys” network, initially set up to recruit for al-Shabab, have now “gone to fight jihad in Syria,” Ellekhlifi being the most obvious example. But Emwazi’s timeline between his joining this network in 2006 or 2007, and his journeying to Jabhat an-Nusra in Syria in July 2013—he only later joined ISIS—is murky. There are, however, many details now available, especially between 2009 and 2010. For the sake of brevity, however, I shall make that the next post …

Pingback: Mohammed Emwazi’s Path To The Islamic State | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Who Killed The Anti-Assad Imam In London? | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Al-Qaeda Central in Syria | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Rise and Fall of Mohammed Emwazi | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The End of the Line for “The Beatles” of the Islamic State | The Syrian Intifada