By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on August 24, 2015

Book Review: The Assassins: A Radical Sect in Islam (1967) by Bernard Lewis

This review can be read in six parts: one, two, three, four, five, and six.

Abstract

The fourth Caliph, Ali, was assassinated during a civil war that his supporters, Shi’atu Ali (Followers of Ali), lost to the Umayyads, who thereafter moved the capital to Damascus. The Shi’a maintained that the Caliphate should have been kept in the Prophet’s family; over time this faction evolved into a sect unto themselves, which largely functioned as an official opposition, maintaining its claim to the Caliphate, but doing little about it. Several ghulat (extremist) Shi’a movements emerged that did challenge the Caliphate. One of them was the Ismailis. Calling themselves the Fatimids, the Ismailis managed to set up a rival Caliphate in Cairo from the mid-tenth century until the early twelfth century that covered most of North Africa and western Syria. A radical splinter of the Ismailis, the Nizaris, broke with the Fatimids in the late eleventh century and for the next century-and-a-half waged a campaign of terror against the Sunni order from bases in Persia and then Syria. In the late thirteenth century the Nizaris were overwhelmed by the Mongols in Persia and by the Egyptian Mameluke dynasty which halted the Mongol invasion in Syria. The Syrian-based branch of the Nizaris became known as the Assassins, and attained legendary status in the West after they murdered several Crusader officials in the Levant. Attention has often turned back to the Assassins in the West when terrorist groups from the Middle East are in the news, but in the contemporary case of the Islamic State (ISIS) the lessons the Nizaris can provide are limited.

Background

By the time Prophet Muhammad died in June 632, the Islamic Empire stretched over most of the southern Arabian Peninsula. During the time of the four Rashidun (Rightly-guided) Caliphs that followed Muhammad, the Empire expanded quickly, conquering Egypt and a large chunk of eastern Libya; Jordan, Iraq, Syria, south-east Turkey, the Caucasus, and Iran; and parts of eastern Afghanistan and most of Turkmenistan (Khorasan).

The Empire was riven with conflict, however. Three of the four Rashidun were murdered, and the fourth, Ali, was struck down in 661, during a civil war and the Caliphate passed to Muawiya and the House of Umayyad, who moved the capital to Damascus.

After Ali’s death, Shi’atu Ali (Followers of Ali) contended that the Caliphate should have remained in the Prophet’s family. Two events hardened this faction into a sect of their own, the Shi’a.

First, in 680, an insurrection by Hussein, the son of Ali and the Prophet’s daughter Fatima, was defeated at Karbala by the Umayyad Caliph Yazid I.

The Shi’a had maintained a line of Imams whom they maintained were the true claimants to the Caliphate—Hussein being the third; Ali the first and Hussein’s older brother, Hassan, the second. Hussein’s son, Ali ibn Hussein Zayn al-Abidin, the sole survivor at Karbala, was the fourth, appointed instead of Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyyah, a son of Ali’s.

During Ali ibn Hussein’s time as Imam, 680-713, the Shi’a would take the form they would maintain for the next 150 years or so: an official opposition, based in Mecca and Medina, far from the centres of political power, maintaining their formal claim, while doing little to challenge the Caliph—sometimes giving allegiance and even advice to the Umayyads and later the Abbasids. Unsurprisingly, there were Shi’ites who organized to press this claim by force.

Second, in 685, the wave of anguish that overcame the Shi’a after Hussein’s death boiled over into a revolt, led by Mukhtar al-Thaqafi in the name of al-Hanafiyyah. Al-Thaqafi was killed and his revolt crushed in March 687, but his movement survived. When al-Hanafiyyah died in 700 there were claims the Imamate had passed to his son; others said al-Hanafiyyah was not really dead and would, in god’s good time, return to triumph over His enemies.

This concept of the Mahdi, one who will return to establish a reign of justice, recurred in various Islamic messianic movements. The movements would always have the leader, the Imam, who was sometimes also the Mahdi, and the da’i, the summoner, who preaches and recruits, and then leads the followers to victory or martyrdom.

Because of the way Islam spread—the Arab elite ruling over newly assimilated Christian converts and Iranians—it left a lot of room for strife, and because of the nature of Islamic rule, political dissent often took on a religious character.

The first half of the eighth century was a period of major agitation by the ghulat Shi’a sects, especially in the mixed populations of Iraq and the coast of the Arabian Gulf.

In 750, the Abbasids, a branch of the family to which the Prophet and Ali belonged, overthrew the Umayyads with a lot of Shi’a support and a vague pledge to restore ahl al-bayt (the Prophet’s family) to the throne. But in their moment of triumph the Abbasids pulled back and chose continuity; they renounced the sect and the da’is who brought them to power and aligned increasingly stridently with the Sunni ulema. The Arab supremacy of the Umayyad polity would be softened, and with the capital moved to Baghdad in 762 the Abbasids changed the Islamic Empire from a Levantine power to an Asian one. But these changes were not enough for the pious and the frustration led to another wave of extremist and messianic movements.

The decisive split between the extremist and moderate Shi’a occurred upon the death of the Sixth Imam, Ja’afar as-Sadiq, in 765. Ja’afar’s eldest son, Ismail, had been disinherited some time before—probably because of his extremist agitation—and the Imamate went to Ismail’s younger brother, Musa al-Kazim, who became the Seventh Imam, and through him the line of “official” Shi’ism continued until the Twelfth Imam. But Ismail had supporters and they broke away, cultivating a sect in secret, which evolved into the Ismailis or Seveners. (An earlier disagreement of this kind after the death of the Fourth Imam led to a schism that formed the Zaydis or Fivers.)

In 873, the Twelfth Imam, the four-year-old Muhammad al-Mahdi, disappeared. For seventy-two years contact was supposedly maintained through four mediators. This was the “Minor Occultation”. After the last of these four deputies died in 941, the “Major Occultation” began and continues to the present.

The Ismailis

Having cultivated their sect in the shadows since 765, the Ismailis emerged in public in 899 when a branch—the Carmathians, whose relationship to the main body of Ismailism is uncertain—formed a millenarian republic, covering part of eastern Arabia, Qatar, and Bahrain. In 903, the Carmathians tried to invade Syria; they were defeated but their attempt revealed significant local support for the Ismailis even at this early date. The Carmathians’ most (in)famous act is the sacking of Mecca, led by Abu Tahir al-Jannabi, in 930, after taking Kufa in 927 and threatening Baghdad in 928. The Carmathian challenge was contained by the Abbasids in 976; Bahrain broke away in 1058; and a Seljuk army besieged the State in 1067 and overran it in 1074. But for more than a century, the Carmathian State served as a base of propaganda and military agitation against the Abbasid Caliphate.

The major Ismaili challenge to the Sunni order came in 909. Having dispatched missionaries to North Africa, Yemen, India, and beyond, and gained enough converts, the Ismailis were powerful enough to unveil their Imam, Abdullah al-Mahdi Billah, who proclaimed himself Caliph and Mahdi. Calling themselves the Fatimids, in reference to the Prophet’s daughter and Ali’s wife, the Ismailis established a polity in North Africa, with their capital in Tunisia, holding essentially everything west of that (except for Morocco, held by a Zaydi dynasty, and Iberia) plus Sicily.

The Ismailis were hell-bent on expansion east into the heartlands of Islam, and Egypt fell to the Fatimids in 969. The Nile Valley, Sinai, Palestine, and southern Syria were soon in Fatimid hands. At its height the Fatimids held the Red Sea coast, Yemen, and the Hijaz, including Mecca and Medina.

The Fatimid Caliphate posed not only a military threat but an ideological one to the Sunni world. The Buyids, a Persian Shi’a dynasty, took Baghdad in 946, but, like the Abbasids, chose to maintain Sunnism and the system already in place—including the Caliph as their front-man. The populations could see what had happened. The Caliph had been a puppet of his Praetorians for a century and this heaped further discredit on the institution. With this final humiliation the Caliphate had seemed on the brink of collapse and fragmentation. Intellectually, the Abbasid Caliphate had become stale. The economic changes of the eighth and ninth centuries had created a dislocated society and inequalities that were the source of much resentment. The “dry legalism and remote transcendentalism of the orthodox faith … offered little comfort to the dispossessed,” Lewis writes. The new and vibrant Fatimid faith gained many supporters and agents in the Sunni lands, especially Persia and Central Asia.

The Fatimids’ success was also the cause of their biggest problems: the Ismailis never quite came to terms with being a State, and from the first there were splits between the “conservatives” and those who wanted a permanent revolution. This led to some armed rebellions and schisms, the most serious occurring in the early 970s, during the reign of the fourth Fatimid Caliph, al-Muizz li-Din Allah. As the Fatimids swept across Syria they encountered the Carmathians, who turned on the Fatimids. The Fatimids put down this revolt. Another schism was formalized in 1021 after the sixth Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah was murdered in mysterious circumstances and a group of Ismailis said al-Hakim was not dead and had gone into occultation, thus they refused to recognize his successor. This faction became the Druze.

The Fatimid Caliphate died long before it was formally abolished. 934 to 1055 is what Fouad Ajami calls the “Shi’a century,” and it was as that period closed out that the Fatimid Caliph was becoming a puppet of the military, a process completed in 1074, when the eighth Fatimid Caliph, al-Mustansir, “invited” Badr al-Jamali, the military governor of Acre, into Cairo. Al-Jamali took on the three titles of Commander of the Armies, Chief of the Missionaries, and vizier—signifying his total control over the military, religious, and civilian wings of the government. This aroused considerable unrest among the Ismailis, especially their adherents in Persia, but it was in January 1094 that the Persian Ismailis would completely break with Cairo.

Almost simultaneously, al-Jamali and al-Mustansir died. Al-Jamali was replaced by his son, al-Afdal. Al-Afdal split the Ismaili world entirely when he chose to ignore al-Mustansir’s designated heir, Nizar, his eldest son, an adult with all the connections of his father’s court, and to instead appoint al-Mustansir’s younger son, al-Mustali, a youth without allies who was thus totally dependent on his military patron. The Persian Ismailis flatly refused to accept this, insisting that Nizar was the rightful Imam, hence being called “Nizaris,” and severed all connection with Cairo. In Egypt itself, there were revolts, and Nizar personally fought on until 1097 when he was killed in prison in Alexandria.

The Origins of the Nizaris in Persia

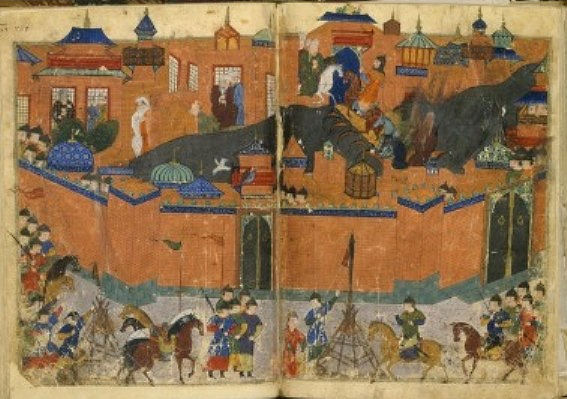

Alamut fortress

Hassan-i Sabbah would lead the Nizaris in Persia. Recruited in Rayy, near Tehran, by the chief dawa (missionary) of the Fatimids in 1072, Hassan-i Sabbah went to Egypt between 1078 and 1081, before returning to Iran to proselytize. In 1090, Hassan-i Sabbah won control of the fortress of Alamut in north-west Iran, which would become the headquarters of the Nizaris. Throughout the 1090s, the Nizaris gained control of further castles in Daylam, specifically the Rudbar area; in the southwest of Iran between Khuzestan and Fars; and in the east in Quhistan. Most impressive was the capture of the fortress at Shahdiz, near Isfahan, in 1096-7.

The Daylamis were a notoriously rebellious and hardy people; one of the last to convert to Islam, they were then among the first to assert their independence within it, first politically by forming a separate dynasty and then religiously by converting to Shi’ism.

Quhistan was one of the last refuges of Zoroastrianism, and had required the armies of Islam to remove a few more obstacles than elsewhere to allow them to convert to the True Faith. Quhistan was chafing under the rule of the Seljuks, a Turkic people from Central Asia who had begun migrating west in the sixth century, even before the advent of Islam. By the late eleventh century, the Seljuks had colonized and taken rulership of some of the heartlands of Islam, a process that would continue unto completion with the Ottomans, a Seljuk House in Anatolia, taking custodianship of most of the Islamic world in the early sixteenth century, forming the last and greatest Islamic Empire. In Quhistan, an oppressive Seljuk officer had pressed his luck too far and tried to demand the daughter of a local lord. Hassan-i Sabbah’s agents had had great success in any case in Quhistan and, with the defection of this lord to the Nizaris, Quhistan’s conversion took on the character of a popular revolt. The Ismailis succeeded in creating effectively a contiguous State in Quhistan, as they later would in Rudbar.

From these fortresses the Nizaris would wage a campaign of assassination against the Sunni Islamic monarchies, intending to frighten, weaken, and ultimately overthrow them. Hassan-i Sabbah trained a cadre of men, the fida’i or fedayeen (men of sacrifice), whose weapon of choice was always the same: the dagger. The Nizaris never used other available weapons like poison or bows. The murders were ceremonial; the killers rarely made any effort to escape, often being killed on the spot. There is even evidence that the Nizaris considered it shameful to survive. This vaguely resembles suicide bombing, but it is not the same: suicide is strictly forbidden in classical Islam, and the Nizaris adhered to that.

The Nizaris greatest foe at their inception was the Seljuk Empire, the most powerful Sunni polity. In this struggle the Nizaris had an advantage: while formally a unified territory under the Isfahan Sultan, the Seljuk Imperium was in fact subdivided into three competing power centres: Isfahan, the capital, held by Berkyaruq; Baghdad, where Berkyaruq’s half-brother, Muhammad Tapar, ruled; and Khorasan, where Tapar’s full brother, Ahmad Sanjar, was ruler. Tapar took over in Isfahan after Berkyaruq died in 1105, and Sanjar replaced Tapar upon his death, ruling in Isfahan between 1118 and 1157.

In October 1092, the Nizaris brought off the first assassination, killing Nizam al-Mulk, the vizier in Isfahan who had been the real ruler for twenty years. Several efforts were made by Berkyaruq to suppress the Nizaris but he was unsuccessful, not least because he was continually distracted with intra-Seljuk fighting. By 1101, the Nizaris had become so bold—and infiltrated Sultan Berkyaruq’s court so badly—that he reached an agreement with Sanjar to join forces against the Nizaris. In short order, Sanjar laid siege to the Nizari statelet in Quhistan. With the Tabas fortress on the verge of falling, the Nizaris used a simple expedient: they bribed Sanjar’s emir to go away.

Between 1101 and 1103, the Nizaris cut down the Mufti of Isfahan, the prefect of Bayhaq, and the chief of the Karramiyya, a militantly anti-Ismaili order. The murder of Seljuk officers and officials had (temporarily) become too difficult as the Nizaris coped with a military onslaught, but civil and religious dignitaries who legitimized the anti-Ismaili campaigns or stirred up opposition to their doctrines and/or mob violence were punished.

With the reprieve, the Nizaris rebuilt, just in time for a renewed offensive by Sanjar’s emir in 1104. This time Tabas and several other Nizari fortresses fell; Ismaili settlements were pillaged and some of their inhabitants enslaved. But then the emir’s army curiously withdrew in exchange for a pledge that the Nizaris “would not build a castle, nor buy arms, nor summon any to their faith”. The bizarrely inconclusive campaign led to only one result: the Nizaris were soon back in control of Quhistan.

Terrorism by definition is supposed to invoke fear, and the Nizaris found room for maneuver by inciting this in their enemies. A notable incident after Mahmud II replaced Tapar in Baghdad in 1118 was Hassan-i Sabbah using a large sum of money to bribe a eunuch, sending him a dagger to stick in the ground beside the Sultan’s bed. Hassan-i Sabbah then sent a message to Mahmud II:

Did I not wish the Sultan well that dagger which was stuck into the hard ground would have been planted in his soft breast?

There is considerable evidence that after this the Baghdad Sultan inclined not to antagonize the Nizari Ismailis.

The Nizari Mission in Syria

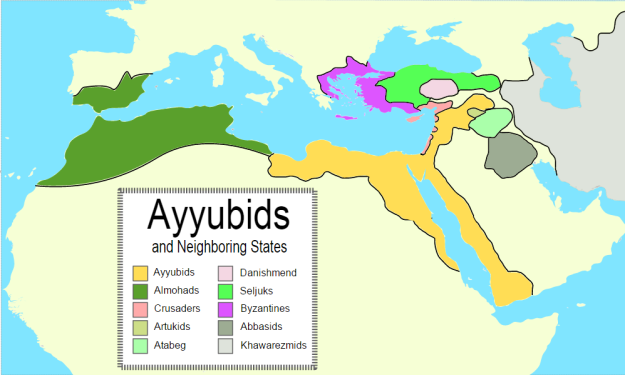

The Nizaris dispatched agents from Persia to Syria in 1103, who sought to replicate the strategy of capturing fortresses for a revolutionary campaign against the Seljuks, who had by this point conquered everything from Central Asia, up to eastern Anatolia, and the Mediterranean coast. The only part of the Middle East not held by the Seljuks was Egypt, held by the Fatimid Caliphate, and the coastal strip of Palestine and Lebanon/Syria, which had been held by the Fatimids and was now held by the Crusaders.

The First Crusade was proclaimed in 1095, and the Crusaders established three Latin States in 1098-99—Edessa, Antioch, and Jerusalem—before adding a fourth, Tripoli, in 1104. The Crusader intrusion as the Seljuk polity of the late Tutush broke down no doubt stressed Syria’s society and made it more receptive to the Nizaris’ message of messianic hope. The Crusaders’ presence, however, had minimal impact. Movements later arose bent on expelling the Crusaders (see part three), but their reasoning was local: they were making a bid for the leadership of the Sunni world. The Crusader “occupation” did not arouse widespread popular resentment or rejection; instead the local polities collaborated (and conflicted) with the Crusader realms as-and-when needed in the usual pattern of State-to-State relations.

The Nizaris chose to bring their “New Preaching” from Alamut to Syria, rather than neighbouring Iraq, because Syria presented more opportunities. Unlike the river-valley societies of Egypt and Iraq, Syria had no history of political centralization; rather to the contrary. Syria was a volatile polity and her coast—between the Taurus Mountain range in what is now southern Turkey and Sinai—offered a mountainous terrain, perfect for the Nizari tactic of entrenchment in fortresses, which was also fragmented politically and religiously opportune with numerous particularisms, including Shi’ite ghulat sects: the Old Preaching (Mustali) Ismailis, the Druze, and the Nusayris/Alawis.

Though the Nizaris are often referred to as the Assassins, it is only the Syrian-based branch of the Nizaris that acquired that name, derived from the Arabic al-Hashishiyya, originally meaning herbage, later specialized to Indian hemp/cannabis. It was, in short, a term of abuse in Syria, likely a reference to (and perhaps an explanation for) the Nizaris’ incredible beliefs and extravagant behaviour. The first reference to the Syrian-based Nizaris as al-Hashishis appears to be in 1123 by the Fatimids—ruled at this time by Caliph al-Amir, whose hatred of the Nizaris was notorious. The Fatimids were, jointly with the Sunni rulers, regarded as the Nizaris’ main enemy. But the popularization of the term seems to have come later in the twelfth century during the Nizaris’ Resurrection period. (For an expanded look at the etymology of Assassins, see Pieter Van Ostaeyen.)

For all the advantages Syria possessed for the Nizaris, they still found it far more difficult than in Persia to entrench themselves, perhaps because all of the Assassin leaders were Persians. It took three attempts for the Nizaris to establish themselves in Syria.

In 1085, Tutush had established the first independent Seljuk polity, in Syria, when he broke with the supreme sultanate in Isfahan, held by his brother, Malik-Shah I. Upon Tutush’s death in 1095, his unified realm shattered, with pieces now ruled over by various Seljuk princes and officers, the most important of whom were Tutush’s sons, Ridwan who held Aleppo and Duqaq who held Damascus.

Between 1103 and 1113, the Nizaris tried to create a base of operations under Ridwan’s patronage in Aleppo. Aleppo had an important Shi’ite population and was conveniently near the ghulat Shi’a areas of Jibal al-Summaq (the Idlibi plains where the Druze are based) and Jibal Ansariya (named for its Nusayri/Alawi inhabitants). It is likely that Ridwan—locked in a struggle with Duqaq—was implicated in the Assassins’ first murder, that of Homs ruler Janah ad-Dawla.

After Ridwan’s death in December 1113 and the instigation of a pogrom by Aleppo’s militia leader, Ibn Badi (whom the Assassins would kill in 1119), the Nizaris looked south, where they found a patron in Tughtigin, who ruled Damascus after Duqaq died in 1104.

It is worth noting, however, that in the spring of 1114, the Nizaris in northern Syria were still strong enough to lead an open attack in battle formation from Afamiya and Sarmin against the Muslim stronghold of Shayzar, and it was not until 1124 that the Nizaris were completely expelled from Aleppo City.

By late 1126, Bahram, the Assassin leader, had appeared openly in Damascus, and the Assassins were given a building in the city from which to operate under official protection. Bahram would soon take an important role in local politics. Bahram’s first demand, with his newfound influence, was for a castle; Tughtigin, gave the Assassins a fortress in Baniyas.

In early 1128, two events severely weakened the Assassins: Bahram was killed in a scuffle with local tribes in Wadi al-Taym, and Tughtigin died. Though Tughtigin’s vizier, al-Mazdagani, maintained his support for the Assassins, an anti-Ismaili spasm of the kind that had followed Ridwan’s death in Aleppo would occur in September 1129, orchestrated by Damascus’ new ruler, Buri, and some of his senior officials. Al-Mazdagani was murdered and a mob massacred probably more than 10,000 Ismailis. So ended the second Nizari attempt to embed in Syria.

The Assassins were in some disarray, as evidenced by the fact that the counterstroke against their Syrian enemies came from Alamut: two Nizaris sent from Persia infiltrated Buri’s security detail and struck him down in May 1131.

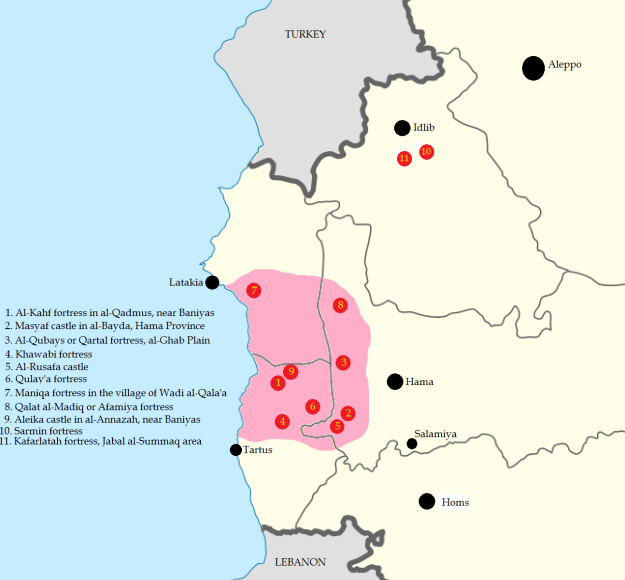

Between their 1129 destruction in Damascus and 1149, little is heard of the Nizaris in Syria, but they were evidently working to consolidate. The Assassins captured al-Qadmus/Kahf fortress in the Baniyas area in 1132 and their most important fortress in Masyaf, east of Hama, in 1141, and the Assassins’ most active and important period was still in the future.

The death of Hassan-i Sabbah and The Resurrection

Hassan-i Sabbah, the Nizaris’ first and most successful leader, died in May 1124. Hassan-i Sabbah was a fanatic who sternly imposed the Holy Law—even executing one of his own sons for drinking wine and another son (mistakenly) for an unauthorized assassination. An extreme ascetic and recluse, Hassan-i Sabbah left his house twice in the thirty-five years after taking Alamut. Hassan-i Sabbah’s great skill was in weaponizing the discontents of the dispossessed and refining the doctrine of al-dawa jadida (the new preaching).

Hassan-i Sabbah never claimed to be the Imam, merely the only one who knew what the Imam wanted. Hassan-i Sabbah confirmed the Ismaili doctrine as essentially authoritarian, where the believer must follow an Imam, the only source of truth, who has been appointed by god (unlike the Sunni view where the believer can choose an Imam).

The Nizaris’ history divides into essentially four parts after this:

- 1124-1164: Buzurgumid, commander for twenty years at the Lamsar fortress, close to Alamut and nearly as important, took over from Hassan-i Sabbah. Under Buzurgumid, his son Muhammad, and the first eighteen months of the rule of his son, Hasan, the Nizaris in Persia evolve toward being merely one principality among many, with normal relations, including alliances, with their neighbours.

- 1164-1210: Under the leadership of Hasan and his son Muhammad II, the Resurrection is proclaimed, ending the Holy Law and revealing esoteric truths to the faithful, inaugurating Paradise on earth.

- 1210-1221: The leadership of Jalal ad-Din Hasan, Muhammad II’s son, turns the Nizaris to a form of quasi-Sunnism, with the shari’a reimposed sternly, and the Nizaris even receive the blessing—and the alliance—of the Caliph of Baghdad.

- 1221-1270s: In the final phase, Jalal ad-Din’s son, Ala ad-Din, and his son RuknuddeenKhurshah returned the Nizaris to a form of “orthodox” Ismailism.

These changes were all felt in Syria, where agents of Alamut were in control of the Nizaris.

**************************

In Persia, Sanjar, by now Supreme Seljuk Sultan in Isfahan, sent an army to capitalize on the Nizaris’ change of leadership—which in the Seljuk realms invariably commenced a power-struggle and instability—and attacked Alamut and Quhistan in 1126, with orders to treat the Nizaris as infidels, slaughtering and enslaving them; showing how entrenched the Nizaris had become, this ended in fiasco. The Nizaris increased the size of their statelet and added a new and powerful fortress in Rudbar at Maymundiz during the war. A Seljuk vizier was assassinated in March 1127, and by 1129, Sanjar sued for peace.

In August 1135, the Nizaris achieved their greatest ever coup. In June of that year, the Baghdad Sultan Mas’ud, who had taken the throne against the Caliph’s wishes in a struggle that continued after his accession, had captured the Caliph, al-Mustarshid. The Nizaris managed to get into the prison camp at Maragha, and struck down the Caliph, the titular head of Sunni Islam. There were seven days and seven nights of celebration at Alamut. In June 1138, the Nizaris followed this up by killing al-Rashid, the son and successor of al-Mustarshid. Al-Rashid had been deposed by Mas’ud and fled to Mosul with Imad az-Zangi; on a trip to Isfahan the Nizaris intercepted al-Rashid.

In August 1164, the Lord of Alamut, Hasan II, announced, from a pulpit arranged so the audience had its back to Mecca, that he had received a message from the Hidden Imam revealing his secrets. Hasan was the Imam, whose commandments were binding on the believers, and al-Yawm al-Qiyama (The Day of Resurrection) was here, a spiritual event, not a physical one. The Imam’s knowledge of the mystery of creation revealed, and the fact there would be no reckoning in the next world but that Paradise could be had right then on earth, which Islam says is impossible, meant the shari’a had served its purposes and was abolished. A banquet was then held in the midst of what was usually a fast, this being Ramadan. A Sunni chronicler records that the “nest of heretics … openly drank wine upon the very steps of that pulpit”.

Those among the Nizaris who resisted the abolition of the Holy Law and stuck to the old ways were executed. A brother-in-law of Hasan’s murdered him in January 1166 accusing him of heresy, but Hasan’s son, Muhammad II, took over at Alamut and continued the Resurrection. The latter decades of the twelfth century, however, were politically uneventful for the Persian Nizaris; very little is recorded of them in that time. But this was just the period when the Syrian-based Nizaris were at their most active, performing the deeds that would later pass into legend.

In Syria, in 1162, Sinan ibn Salman ibn Muhammad, better known as Rashid ad-Din Sinan, a protégé of Hasan’s, was revealed to the Nizari faithful as their leader. In the West, Sinan would become known from his Arabic honourific, Shaykh al-Jabal, “The Old Man of the Mountain”. Sinan would implement the Resurrection in Syria.

There were some public excesses, which one Sunni chronicler gleefully exaggerated as follows:

The people of Jabal al-Summaq gave way to iniquity and debauchery, and calling themselves “The Pure”. Men and women mingled in drinking sessions, no man abstained from his sister or daughter, the women wore men’s clothes, and one of them declared that Sinan was God.

The ruler of Aleppo sent an army against this depraved enclave, but Sinan convinced him to withdraw, and Sinan himself destroyed this runaway enclave.

There is an interesting contrast between the way the Resurrection played out in Persia and in Syria. In Persia, the Resurrection was faithfully recorded by the Nizaris and wholly missed by the Sunni world, only recorded later from the documents captured after the fall of Alamut. In Syria, the Nizaris seem to have forgotten the Resurrection while the Sunnis did not, writing with relish and horror of the goings-on among the Nizaris after the end of the law.

There is a minor ambiguity about whether Sinan at all points took orders from Alamut; there is some indication Sinan claimed divinity personally at a certain point. In either case, Alamut’s control over the Assassins was restored for certain after Sinan’s death.

It is during Sinan’s leadership, specifically the 1170s to 1190s, amid the Resurrection and the fastest pace of assassinations, that the Nizaris became best-known to the West, which is no doubt the reason for some of the lurid stories about the Assassins. While the Assassins had murdered a Crusader before—Raymond II of Antioch in 1152—it was the slaying of Marquis Conrad of Montferrat, the King of Jerusalem, in Tyre, in April 1192, which would garner the most attention in Europe.

The Assassins’ Struggle Against the Sunni Unifiers: Nooradeen az-Zangi and Saladin

The Zangid atabeg (lord) of Mosul, Imad ad-Deen az-Zangi, had extended the writ of his dynasty from Mosul to Aleppo in 1128, and after he was assassinated by one of his Frankish slaves in September 1146, the kingdom was divided between his eldest son, Sayf ad-Deen Ghazi, who ruled in Mosul, and his younger son, Nooradeen az-Zangi, who ruled in Aleppo.

From the mid-1140s, Nooradeen had embarked on a project to unify the Sunni world, which meant imposing a strict orthodoxy and expelling the Crusaders. This made Nooradeen the primary antagonist of the Assassins. Beyond this structural fact, Nooradeen abolished the Shi’ite call to prayer in Aleppo in December 1148, a virtual declaration of war against the Nizari Ismailis. In June 1149, a Kurdish Assassin leader, Ali Ibn Wafa, emerged, in collaboration with Raymond of Antioch, to attack Nooradeen. This was among the few recorded events of the Assassins since they were uprooted from Damascus in 1129.

By the time Nooradeen died in 1174, he had brought Damascus and Aleppo under his direct rule, with his son ruling Mosul in his name, and a Kurdish deputy, Saladin, ruling Egypt, ostensibly under his authority.

The Nizaris helped push the Fatimid Caliphate—jointly with the Sunni order the Nizaris’ main foe—into its grave. In December 1121, Nizari agents from Aleppo had struck down the Fatimid vizier (de facto ruler) al-Afdal, the man chiefly responsible for denying Nizar the Caliphate, and in 1130 Nizaris had killed the tenth Fatimid Caliph, al-Amir, after which not even the Mustalis recognized the Fatimid Caliph as their Imam. There were four more Fatimid Caliphs, but it was a strictly local dynasty, which increasingly lost its independence after Nooradeen dispatched Saladin to Egypt in 1164 to fend off a Crusader attack. When the fourteenth Fatimid Caliph died in September 1171, and Saladin had the bidding-prayer read out in the name of the Abbasid Caliph, Egypt was returned—after two centuries—to the Sunni fold, amid the near-total indifference of its population, which heaped the Ismaili books onto bonfires.

As ever, a power-struggle followed Nooradeen’s death, and the upshot was that by November 1174, Saladin, who was now the claimant to the Sunni hopes of unity and holy war and cleansing the Fertile Crescent of foreign infidels and local heretics, was in control of Damascus and was marching on Aleppo. On his way to Aleppo, Saladin took the chance to raid the Nizari centres at Sarmin, Maarat Masrin, and Jabal al-Summaq, killing most of their inhabitants, after they had been destabilized by a terrible massacre from the Nubuwiyya, an anti-Shi’a Iraq-based Sunni organization. Thus, the Assassins saw in Saladin a mortal threat, ideologically and practically, and began to look more kindly on their old nemesis: the Zangids.

When the Aleppine ruler, Gumushtigin (ostensibly subordinate to the Zangid boy-king as-Salih), appealed for help from the Assassins—the Crusaders having let Gumushtigin down—they had reasons of their own to respond and accept the logistical and financial help of Gumushtigin against Saladin.

In January 1175 and then again in May 1176, the Assassins tried to kill Saladin. Between the attempts, Saladin had won a famous victory in April 1175 over the combined forces of Mosul and Aleppo in Aleppo, leaving as-Salih humbled but in control of Aleppo and only Mosul in active opposition to him. In the first attempt, the Assassins easily penetrated Saladin’s camp around Aleppo but were recognized and, though they killed several people, Saladin was unharmed. The second attempt, during Saladin’s siege of Azaz, saw the Assassins attack Saladin with knives. Saladin was saved by his body armour; several of his emirs were not.

Saladin now took elaborate security precautions—sleeping in a specially constructed tower and refusing to allow anyone he did not personally know to approach him—and, enraged, marched on Masyaf, the Assassins’ most important fortress, closing a siege around it in August 1176. For reasons not wholly clear, Saladin called in his uncle, the emir of Hama, as a mediator and lifted the siege before the Assassins were defeated.

In one telling, Saladin was called away from Masyaf by a Frankish attack in the Bekaa; in the Nizari telling, Saladin was awed by the magical powers of Sinan, and Saladin and Sinan became the best of friends after this. Removing the layers of propaganda and delusion, it is clear enough that some kind of modus vivendi was reached between Saladin and Sinan at this point: there are no further attacks on one-another and even signs of working in tandem.

Historian Kamal ad-Din suggests a reason for this policy change. Sinan sent a messenger to Saladin, and the messenger would not give his message before an audience. Saladin cleared his lower officials from the room, then his senior officials, then finally:

Saladin emptied the assembly of all save two Mamelukes [Turkish slave soldiers], and then said: “Give your message.”

[Sinan’s representative] replied: “I have been ordered only to deliver it in private.”

Saladin said: “These two do not leave me. If you wish, deliver your message, and if not, return.”

He said: “Why do you not send away these two as you sent away the others?”

Saladin replied: “I regard these as my own sons, and they and I are as one.”

Then the messenger turned to the two Mamelukes and said: “If I ordered you in the name of my master to kill this Sultan, would you do so?”

They answered yes, and drew their swords, saying: “Command us as you wish.”

Sultan Saladin … was astounded, and the messenger left, taking [the Mamelukes] with him. And thereupon Saladin … inclined to make peace with [Sinan] and enter into friendly relations with him.

Only two further definite events are recorded by the Assassins in Syria: an assassination and a fire.

Shihab ad-Din ibn al-Ajmi, the vizier of the Aleppine boy-king as-Salih and the former vizier of Nooradeen, is struck down in August 1177 and, under torture, the Assassins confessed that they had been sent by Gumushtigin, formally as-Salih’s military leader but in reality the main power-wielder in Aleppo. However, according to James Waterson, it is “likely that the Assassins were told by Sinan that Gumushtigin was their ’employer’ but Saladin was in fact the paymaster.” It is certainly true that Gumushtigin had little to gain from this murder—indeed Gumushtigin’s enemies used it to bring about his downfall—but Saladin profited from the increased distrust within the House of Zangi. In either case, it shows that deception—properly termed false-flags, even if that term has by now largely passed into the hands of the tin-foil hat brigades—and provocation were features of terrorism from the get-go.

In early 1180, Aleppo’s forces seized al-Hajira from the Assassins. When Sinan’s protests produced no results, the Assassins burned down Aleppo’s market place, causing considerable damage. That none of the arsonists were caught suggests the Assassins could still draw on a degree of Shi’a/Ismaili sympathy in the city.

Sinan died in 1192, not long after his agents cut down Conrad of Montferrat before he could be crowned King of Jerusalem.

Saladin died in March 1193, having added Aleppo and Mosul to his realm of Egypt and Damascus, and had legendarily driven the Crusaders from Jerusalem in September 1187, sparking the Third Crusade in 1189. Richard I (“Lionheart”) would depart back to England from Acre in October 1192 with Jerusalem still in the hands of Christendom’s enemies, but the rest of Saladin’s unified polity would soon unravel, just as Tutush’s and Nooradeen’s had before.

The Nizaris’ Turn to Sunnism

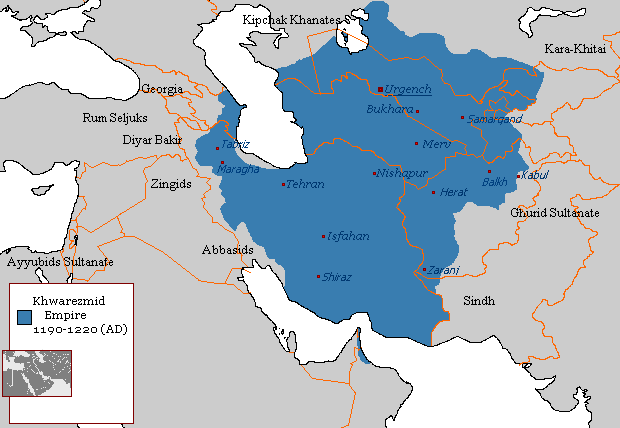

In Persia, a new power was rising in the east: Tekish, the Shah of Khorazm/Khwarezm. In 1194, the Caliph, al-Nasir, was hard-pressed by the Seljuk Sultan of Isfahan, Tughrul II, and appealed to Khorazmshah Tekish for help, providing the excuse for the Khorazmshah to extend into western Iran. Tughrul II was soon killed, taking the Seljuk Empire with him.

The Seljuks had been the major power in Islam for 150 years, and while their rule had ended, the pattern of rule they brought—Turkish colonization, Turkish annexation of local ruling systems, and a stern orthodoxy—remained and was expanded. The Khorazmshah himself was a product of this: the office was descended from a Turkish slave soldier sent to Khorazm as a governor by the Seljuk Great Sultan Malik-Shah.

The extent of the Khorazmian Empire, 1190 to 1220, after the Khorazmshah conquered the Great Seljuk Empire centred in Isfahan.

The Khorazmshah demanded that the Caliph, whose main enemy he had just taken out, recognize the Khorazmshah as Sultan and protector of the Caliph. But al-Nasir had a different script in mind.

Since becoming Caliph in 1180, al-Nasir had led a revival of the Abbasid Caliphate, rescuing some actual power for the Caliphs. With Seljuk power waning, Caliph al-Nasir looked to seize the opportunity for two things:

- To reunify the world of Islam under the moral authority of the Caliph, relieving the battered image of that office.

- Set up a principality—a sort of Vatican City—in Iraq under the effective control of the Caliph, free from outside control or influence.

In service of the second objective, which very much was secondary, the Caliph orchestrated political and military action against Tughrul and later Tekish. Toward his primary objective, the Caliph reached out to the Twelver Shi’ites and Ismailis, and had a surprising amount of success with the Ismailis.

When Jalal ad-Din Hasan became the Lord of Alamut in 1210, he did so after having written letters to the Caliph in Baghdad, Muhammad Khorazmshah (who succeeded Tekish in 1200), and the maliks and emirs of Iraq and beyond to notify them of his intentions to institute orthodoxy upon taking power. Thus, when Jalal ad-Din took over at Alamut and announced that he was a Muslim, the ground had been prepared for him to be believed, and because of the predicament, the Caliph in Baghdad was especially willing to listen.

A decree was issued in Baghdad by the Caliph confirming that the new Lord of Alamut was a part of the House of Islam—”Neo-Muslims,” Hasan and his followers were called. Hasan invited the Caliph to send a delegation to Alamut to remove books from the library that were contrary to Islam. The Caliph’s agents removed the works of Hassan-i Sabbah and of course of Hasan’s own father and grandfather, who had led the Resurrection period.

Jalal ad-Din does not seem to have faced any resistance. The strength of Jalal ad-Din’s position can be seen in his ordering the re-imposition of the Holy Law and being obeyed throughout all of Iran and Syria.

The earlier, pre-Resurrection pattern, of the Nizaris in Persia becoming just one sectarian dynasty among many, reasserted itself with a vengeance. Jalal ad-Din received the Caliph’s sanction to marry into Sunni ruling Houses. Jalal ad-Din left the Alamut fortress, as none of his predecessors had done, and even stayed away for eighteen months without mishap.

Lewis writes:

Instead of dispatching murderers to kill officers and divines, [Jalal ad-Din] sent armies to conquer provinces and cities, and by building mosques and bathhouses in the villages completed the transformation of his domain from a lair of assassins to a respectable kingdom, linked by ties of matrimonial alliance to his neighbours.

Having become a traditional ruler, Jalal ad-Din took up the traditional ruler’s prerogative of changeable alliances. Jalal ad-Din seems to have first favoured Khorazmshah, even having the bidding-prayer read out in his name in Rudbar, but the Lord of Alamut soon transferred his allegiance to the Caliph. Jalal ad-Din had very friendly relations with the rulers of Arran and Azerbaijan against their common foe—the Khorazmshah in Western Iran—and this alliance was blessed by the Caliph. In service of his alliance with the Caliph, Jalal ad-Din had an emir who defected to the Khorazmshah and a Sharif in Mecca murdered. Later, Jalal ad-Din would seek to ingratiate himself to the new and terrible rising power in the east—the Mongols.

The Nizaris Return to “Orthodox” Ismailism

When Jalal ad-Din died in November 1221, his nine-year-old son, Ala ad-Din, became the official Imam, though Jalal ad-Din’s vizier was the effective ruler for some time. Ala ad-Din would turn away from the neo-Sunnism of his father and back to an “orthodox” Ismailism. The changes demanded an explanation.

The Nizari Ismailis did not just believe themselves to be a local principality—still less a mere band of murders. The Ismailis believed themselves to be the holders of a cosmic mission. In trying to explain what had happened—the abandonment of the law, the imposition of Islamic orthodoxy, and the return to Ismailism bound by law—the Ismailis fell back on two principles: taqiyya (dissimulation) and the alternating periods of manifestation and occultation.

The case for dissimulation was easy enough to make: in a time of peril the Ismailis had hidden their beliefs to survive in the world—and god well understood this. In short, Jalal ad-Din’s orthodoxy was written-off as a show needed to help the Nizaris make their way in the world. (In reality, Jalal ad-Din does seem to have been a sincere believer.)

The restoration of the Holy Law by Ala ad-Din was explained by Ala ad-Din’s period being one of occultation: the Resurrection had been manifestation and pre-Resurrection was occultation. The difference with this new time of occultation was that it was not the Imams who were hidden, since the Lord of Alamut now was the Imam, but the true Ismaili mission.

Even amid spiralling disorder at Alamut, caused in no small part by Ala ad-Din’s “erratic” behaviour, the Nizaris managed to capture the city of Damghan, near the fortress of Girdkuh, and apparently tried to capture Rayy, in 1222, as the Khorazmian Empire reeled. In response the final Khorazmshah, Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu, orchestrated a massacre of Nizaris, and in reply to that the Nizaris struck down a Khorazmian officer, Orkhan, near Isfahan in 1227.

The Alamut representative, Badr ad-Din, was en route to the Sultan when Orkhan was killed, intending to improve relations with the Khorazmshah, and naturally wondered whether he would now be welcome at the Khorazmian court. The vizier, Sharaf al-Mulk, having seen the fate of Orkhan, was only too pleased to have a senior Nizari representative in his company and tried to ingratiate himself to Badr ad-Din.

A slight hiccup was provided when, in a “moment of abandon at a drinking session,” Badr ad-Din revealed to al-Mulk the extent of the Nizaris’ penetration of Khorazmian ranks:

“Badr al-Din said: ‘Even here in your own army we have our fida’is, who are well-established and pass as your own men—some in your stables, some in the service of the Sultan’s chief pursuivant.’

Sharaf al-Mulk insisted on seeing them, and gave him his kerchief as a token of safe-conduct. Badr al-Din thereupon summoned five fida’is … [O]ne of them, an insolent Indian, said to Sharaf al-Mulk: ‘I would have been able to kill you … I did not do so because I had not yet received orders to deal with you.’

When Sharaf al-Mulk heard these words he cast off his cloak and sat before them in his shirt and said: ‘What is the cause of this? What does Ala al-Din want of me? For what sin or shortcoming on my part does he thirst for my blood? I am his slave as I am the Sultan’s slave, and here I am before you. Do with me as you will!’

Word of this reached the Sultan, who was infuriated at Sharaf al-Mulk’s abjectness and at once sent orders to him to burn the five fida’is alive. The vizier pleaded for mercy for them, but in vain … A great fire was kindled at the entrance to [al-Mulk’s] tent, and the five men thrown into it. As they were burning they cried out: ‘We are sacrifices for our Lord Ala al-Din’.” …

“[A]n envoy called Salah al-Din came to [al-Mulk] from Alamut and said: ‘You have burnt five of our fida’is. If you value your safety, you must pay a bloodwit of 10,000 dinars for each of them’.”

Al-Mulk paid.

As with the earlier examples of Mahmud II of Baghdad and Saladin’s Mamelukes, it shows how skilled at espionage and infiltration the Nizaris were.

The Nizaris’ relations with the Khorazmians did not come to much: the Nizaris maintained relations with the Khorazmians’ two main enemies—the Caliph in the west and the Mongols in the east—and in 1231 the Sultan Jalal ad-Din would be killed and with him the Khorazmian Empire as the Mongols advanced deep into the world of Islam.

The End of the Nizaris

In 1218, the Mongols reached the Jaxartes River, becoming immediate neighbours of the Khorazmshah. By 1219, Genghis Khan had crossed the river and entered the Islamic world. By 1240 the Mongols had overrun Iran and were invading Georgia, Armenia, and northern Mesopotamia.

In this period, the Nizaris—who never forgot their mission—had dispatched envoys from Alamut to convert the Ismailis of the Gujerati coast from the “old preaching” to the “new preaching”. In time, India would become a main centre of Ismailism.

There is one final documented episode—albeit hazily—from the Nizaris in Syria around this time. The stories of the Assassins’ attempts to kill France’s King (now Saint) Louis IX as an infant can, like all stories of the Assassins operating on European soil, be dismissed as invention. But after King Louis arrived in Palestine in June 1249, there is every indication that he reached a compact with the Assassins, which involved paying them tribute.

The Nizaris were, by the mid-thirteenth century, very much part of the patchwork of Levantine politics, but they maintained the additional lever of power—extracting tribute under threat of assassination—over their neighbours and even, it seems, temporary visitors.

In December 1255, the Lord of Alamut, Ala ad-Din, by this time quite, quite mad, was murdered in his bed. A conspiracy was already underway by Ala ad-Din’s son, Ruknuddeen Khurshah, to reach out to the Mongol Khan to try for terms since the demented Ala ad-Din had taken no precautions, but the scheme—which almost certainly would have ended in a coup to remove Ala ad-Din—became unnecessary.

Ruknuddeen squared matters within the world of Islam—demanding that his subordinates throughout Persia behave as Muslims and keep the roads clear—and then turned to the Mongols to try to surrender on the best possible terms, a decision pushed by the philosopher Nasir ad-Din Tusi, who no doubt thought he could move to a new career under Mongol auspices.

A Mongol army, under the authority of Möngke, the fourth Great Khan based in Peking and led by Hulegu, had already attacked the Nizari bases in Rudbar and Quhistan, though with limited success, by the time Rukhnuddeen’s emissaries reached Hulegu with the Nizaris’ promise of surrender in May 1256. In July, the Mongols reached Alamut, and in November, after several delaying tactics, Ruknuddeen submitted himself, his family, and his treasure to Hulegu. What little treasure the Nizari Imam had was distributed among Hulegu’s troops.

Hulegu indulged Ruknuddeen to a quite surprising extent, providing him camels for breeding and fighting, and, more strikingly, allowing Ruknuddeen to marry a Mongol girl.

Hulegu’s interest in Ruknuddeen was clear: Ruknuddeen could—and did—call on the Nizari castles to surrender without the need for a protracted and sanguinary conflict to subdue them. All-but two of the Nizari fortresses—Lamsar and Girdkuh—capitulated. Alamut had initially resisted, but a few days into the siege in December 1256 its remaining commander changed his mind and surrendered.

Disobedience to the Imam was a grave offence but the Nizari Ismailis might well—and not unreasonably—have believed the Imam was acting under duress and thus his order was taqiyya. Indeed, when Ruknuddeen was taken to Girdkuh in March 1257, he ostensibly called (again) on the fortress to surrender, but it was suspected that he had told them secretly to continue resistance.

Later in 1257, with the surrender of most of the Nizari fortresses and Ruknuddeen having shown he had no further influence on the rest, the Mongols murdered Ruknuddeen. Hulegu had allowed Ruknuddeen to travel to the Mongol capital of Karakorum to meet Möngke, who refused to meet Ruknuddeen and sent word asking what Hulegu was playing at leaving Ruknuddeen alive. At the side of a road, on the edge of the Khangay range, on the way back to Persia, Ruknuddeen was beaten unmercifully, and then put to the sword with his kin.

Lamsar finally surrendered in 1258, and this would be remembered to the Ismailis as the year of their fall. Girdkuh, which had been first besieged in 1253, held out until 1270. The Nizaris briefly recaptured Alamut in 1275, but within a year they were dislodged by the Mongol rulers of Persia.

The Ismailis were obliterated in Rudbar and in Quhistan. The Ismailis survived in minor enclaves in eastern Persia, Afghanistan, former Soviet Central Asia, and India. Some of the Nizari leadership fled to Azerbaijan.

In Syria, it was the Bahri dynasty, which had deposed Saladin’s Ayyubids in Cairo in 1250, that put an end to the Nizaris.

The Mongols sacked Baghdad and murdered the Caliph in February 1258—destroying the Abbasid Caliphate, the titular leaders of Sunni Islam for half-a-millennium—and continued to sweep west. Baybars, the fourth Bahri Sultan, had inflicted the first major defeat on the Mongols in September 1260, halting their advance in Palestine. Over the next decade, Baybars drove the Mongols out of much of Syria and consolidated it under his rule. Baybars, a descendent of the Mamelukes, restored—in name—the Abbasid Caliphate from Cairo in June 1261. In this effort against the Mongols, Baybars had aligned with the Assassins.

Once the Mongol tide had been turned back, Baybars could hardly accept a lethal nest of heretics within his realm. Already in 1265, Baybars had been in a position to demand “taxes”—a cut of the gifts that the Crusaders paid to the Assassins to prevent attacks on the Latin States. Disheartened by the fall of Alamut, the Assassins had meekly accepted. In February 1270, Baybars took direct control of the Assassins’ most important fortress at Masyaf.

The Assassin chief, the aged Najm ad-Din Ismail, was deposed by Baybars and a direct puppet, Najm ad-Din’s son-in-law, Sarim ad-Din Mubarak, the Assassin governor of Ulayqa, was appointed leader but excluded from Masyaf. Sarim ad-Din managed to gain control of Masyaf via a trick, but Baybars restored control before the end of the year and sent Sarim ad-Din as a prisoner to Cairo, where he died, probably of poisoning. Najm ad-Din was restored as Assassin chief by Baybars, to rule conjointly with his son, Shams ad-Din Muhammad, on condition that the Assassins paid tribute to Baybars.

In February/March 1271, Sultan Baybars charged that two Assassins had gone from Ulayqa to Tripoli to meet with Bohemond VI, the Prince of Antioch and Count of Tripoli, to plan the Sultan’s assassination. Shams ad-Din, was soon arrested on the same charge. Najm ad-Din interceded with Baybars to plead his son’s innocence. Baybars agreed to release Shams ad-Din and the other two Assassins on condition that the Assassins surrender their castles and their leaders join Baybars’ court in Cairo; they agreed. Najm ad-Din went to Cairo; Shams ad-Din was allowed to go to Khaf “to settle its affairs,” but immediately began organizing resistance. It was in vain.

In May/June 1271, Baybars seized Ulayqa and Rusafa, and in October, realizing his cause was hopeless, Shams ad-Din surrendered to Baybars, and was initially well-treated. When Baybars learned of a plot being organized by the Assassins against some of the Mameluke emirs, he sent Shams ad-Din and his inner circle to Cairo. Baybars blockade of the Assassins’ castles continued.

Interestingly, Baybars seems to have annexed the Assassins for a time. The attempted assassination of Edward II of England in 1272 was executed by the Assassins but ordered by Baybars, and the same is perhaps true of the murder of Phillip of Montford in Tyre on August 17, 1270. Baybars is reported to have threatened the Count of Tripoli, Bohemond VI, in April 1271, with assassination—this at the same time Baybars was besieging Tripoli and had just accused the Assassins of plotting with the Count to kill him. But all reports of Nizari assassinations after the thirteenth century are myths.

By 1273, all of the Assassins’ castles were in Baybars’ hands. This was the end of the Nizaris as a challenge to the Sunni order.

The Aftermath of the Nizaris’ Defeat

Unlike in Persia, the Nizaris in Syria were allowed to survive as a semi-autonomous community. For a long time the Nizaris concentrated in Tartus Province, around the old stronghold of Kahf/al-Qadmus. Al-Qadmus fortress was destroyed in 1830 by the invading forces of Egypt’s ruler, Muhammad Ali. In the 1840s, the Ismaili chief of al-Qadmus successfully lobbied the Ottoman Empire to allow Ismaili resettlement of the abandoned town of Salamiya. Pressure from the Alawis against the Ismailis hastened their departure from Baniyas to Salamiya, where the Ismailis still live.

Interestingly, while many minorities have clung to the Assad dictatorship, especially as the Syrian rebellion has taken on an increasingly Islamist colour, Salamiya has been a centre of peaceful opposition. Salamiya is an unwelcome reality to Assad, who presents himself as a shield for the minorities, and groups like Jabhat an-Nusra that also need this stark sectarian faultline between a Sunni rebellion and a godless tyranny.

In the fourteenth century the Nizaris of Syria and Persia split over the claimants to the Imamate, and ended all contact with one-another thereafter. The Ismailis reappear in history in the sixteenth century, after the Ottoman conquest of Syria, when the census-makers record al-qila al-dawa (the castles of the mission). The only distinguishing feature of the Ismailis after that is their payment of a special tax.

In the early nineteenth century, interest in the Assassins—and the Crusades—revived. One reason was Napoleon’s brief occupation of Egypt (1798-1801), which made numerous records available. Rousseau, the French consul-general in Aleppo, and the English traveller J.B. Fraser were among those in this period who confirmed the survival of the Ismailis in Syria and gathered information from local informants. Oddly, there was much less interest in Persia, even though the castle of Alamut still stood. Perhaps the major spur to reinterest in the Assassins was the French Revolution, which the reactionaries like Joseph von Hammer were sure had been orchestrated by a secret cabal of anti-religious nihilists—the Illuminati or the Freemasons—and this suggested to them a parallel with the Assassins.

It was the European historiographers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries who created the legend of the Assassins—drugged cultists who killed the Crusaders—that remains popular in the West to this day. This legend annexed and expanded the Sunni myth of narcotics-driven killers warring against the true religion so as to allow comparisons with the supposed cabals behind the French Revolution, and put a false emphasis on the Crusaders in the Assassins’ story, when in fact, as demonstrated, the Crusaders were wholly incidental to the Nizaris’ objectives.

The most significant return to history for the Ismailis was in the mid-nineteenth century. The Khojas, a Muslim sect of mainly traders around Bombay, had refused in 1827 to make their customary payments to the head of their sect, Hasan Ali Shah, the son of the Persian Shah, Fath-Ali Shah Qajar. The Shah had appointed Hasan Ali as governor of Mahallat and Qom in 1818, giving him the title of Aga Khan. The Aga Khan dispatched emissaries to Bombay and most secessionists relented.

Having led an unsuccessful revolt against the Shah and then offered some help to the British in the closing stages of the First Anglo-Afghan War (1841-2), the Aga Khan went to Bombay and set himself up as the effective head of the Khoja community.

In April 1866, a group of secessionists filed suit in the High Court of Bombay asking that the Aga Khan have an injunction levied against him to stop him “interfering in the management of the trust property and affairs of the Khoja community.”

Judgment was rendered in November 1866: the Khojas were Ismailis, who had been converted four-hundred years previously by a Persian missionary, and were “still bound by ties of spiritual allegiance to the hereditary Imams of the Ismailis,” descended from the Lords of Alamut, the Fatimid Caliphs, and ultimately the Prophet Muhammad.

This led to the discovery of other Ismaili populations in southern Arabia, Russia, and Afghanistan.

Conclusion

The Nizari Ismailis did not invent assassination, of course; only lent it their name. The Ismailis were “part of a long tradition that goes back to the beginnings of Islam … of popular and emotional cults in sharp contrast with the learned and legal religion of the established order.” Still, the Nizaris did rely on the Holy Law. The ideal of Islamic governance might be authoritarian, but it is not arbitrary; if a ruler crosses the shari’a it becomes a duty to resist. This element became gradually more marginal as the religion formed into a State and Empire, but it was there and many other sects had called on it in their opposition to the prevailing regimes. The Nizaris were the first to call up this tradition of righteous rebellion and combine it with an effective opposition organization.

In their use of conspiracy, assassination, and even the ceremonial nature of the murders and the weapon-cult, the Assassins were hardly unique. But they might well be the first terrorists: those who, at an overwhelming disadvantage in conventional terms, used unconventional means in a planned, long-term campaign of targeted violence as a political weapon with the intention of overturning the established order.

The assassinations almost all targeted Sunni Muslims, not native Jews and Christians, and not Shi’ites. The aim was to frighten, weaken, and ultimately overthrow the Sunni regimes. In the course of this strategic objective, tactical decisions were taken: examples were made of Sunni clerics who were especially vociferous against the Ismailis; leaders and officials of areas that the Ismailis wanted to expand into were removed; revenge was taken on those who attacked the Ismailis; and tactical and long-term strategic purposes combined in the murder of great figures like the two Caliphs, the vizier Nizam al-Mulk, and the two attempts on Saladin. The few attacks on Crusaders seem to follow Rashid ad-Din Sinan’s accord with Saladin—i.e. were likely not sanctioned by Alamut—and the ones that were sanctioned from Alamut came in the time of Hasan’s return to orthodoxy and the alliance with the Caliph.

It is very important to note that the Nizaris’ careful use of terrorism targeted the rulers of brittle, autocratic Islamic governments, based on familial, tribal, and other transient loyalties, which made them vulnerable to destabilization by assassination. The Assassins were focused on the Muslim world in any case, but among the reasons they never wasted time killing Templars or Hospitallers in the Latin States was that these orders of Knights could replace a slain man with another just as good. It was the genius of Hassan-i Sabbah to perceive this weakness in the Islamic monarchies, and to differentiate them from mature, bureaucratic organizations.

The crucial distinction is the two periods of the Ismailis—between the ninth and eleventh centuries, and between the eleventh and mid-thirteenth. The Nizaris, who operated in the latter period, never offered an ideological threat to the Sunni world. The Fatimid theology was a sophisticated, urban intellectualism: the pious could find a Tradition and Qur’anic teaching equal to the Sunnis; there was a philosophical framework to sustain the intellectuals; an emotional and personal faith with the promise of the Truth to the spiritual; and a well-organized opposition movement with a real chance of overthrowing the established order to the discontented. The Nizaris presented a political-military challenge to the established order, and contended for the hearts of the believers, but the magical qualities of the New Preaching never seem to have been a contender for the minds of the Sunnis; there were no significant defections of poets, philosophers, and theologians to the Nizaris as there had been to the Ismailis in earlier times.

Part of the reason the Nizari challenge was intellectually quarantined comes down to the class distinctions between the followers of the Old Preaching and the New Preaching, and the very structure of the Nizaris. The New Preaching’s leaders were educated townsmen—Hassan-i Sabbah was a scribe from Rayy and Sinan was a schoolmaster from a notable family in Basra—but the Nizaris were based in their fortresses, drawing on sympathetic surrounding populations, where the only recruits were rural peasants and mountaineers.

Several dozen of the assassinations are said by various sources to have been orchestrated by third parties, and it is certainly true that the Nizaris, from their earliest, most fervent days, never disdained the help of a cynical or frightened Sunni ruler against another; any help was welcome in their quest to upend the Sunni order. Various military and political officials, including some leaders, saw advantages in tacit understandings with the Assassins, either to ward off the threat of assassination or to use that threat (and sometimes the reality) against other Muslim polities. Infiltration and provocation therefore have a long history in terrorism.

The confusion is furthered by the fact that for the Nizari leaders there were great advantages both in having the blame for the murders placed on others since it could divide enemies and in taking credit for murders the Nizaris didn’t commit. The cases of Caliph al-Mustarshid and Shihab ad-Din ibn al-Ajmi (where Sanjar and Gumushtigin, respectively, were blamed, sowing distrust among the Sunni rulers) or Conrad of Montferrat (where Richard I was blamed, sowing distrust among the Crusaders) are good examples of the former. It is not clear whether the actual executors of assassinations were consciously lying when they confessed—as they did in the case of Conrad and al-Ajmi—that they had been put up to it by a third party, or whether the Nizari leadership lied to its agents to further its strategic goals. On the other hand, the Assassins provided a convenient scapegoat for quite a number of ordinary political murders; the Assassins willingly played along by claiming any murders they were accused of because it helped to further their mystique and therefore the impact of their terrorism—their ability to extract rents, for example.

The Nizaris’ place in history is the culmination of a series of messianic movements in Islam. While the intellectual challenge from the Ismailis had run aground by the time the Nizaris emerged, the Nizaris still managed to marshal the discontents of the Muslim world into an ideology that could sustain their fedayeen and an organization that could threaten the ruling order.

That said, perhaps the most consequential conclusion about the Nizaris is their total failure to overthrow the existing order and their utter defeat. Even at the height of their power, the Nizaris never held a major city and “their castle domains became no more than petty principalities.” The Nizaris’ supporters remain to us now in a few towns in Syria and Iran as peaceful schismatics. But, Lewis concluded, the “messianic hope and revolutionary violence” that impelled the Nizaris had by no means died with them, and new causes of anger, new dreams, new weapons, and new means of attack have and will impel successors.

Interest in the Assassins has revived when radical sects of Middle Eastern origin are capturing headlines through murder. The obvious modern comparison is with ISIS.

ISIS has in common with the Assassins a millenarian and messianic vision, for which men are prepared to die, as an alternative to a stagnant, discredited order, and an effective military organization to challenge that order. ISIS, like the Nizaris, is a minority, extremist sect that has managed nonetheless to capture a base, where it converts the local population and from which it can launch political-military warfare. Like the Assassins, ISIS combines fanatical zeal with strategic planning. And, crucial for Westerners, in the case of both the Assassins and ISIS: it’s not about us; neither minds catching us in the crossfire, but their objectives are local. One might also hope that the Assassins’ annihilation presages ISIS’s fate.

ISIS’s military base, however, is far more substantial than the Nizaris’ ever was, and ISIS, unlike the Nizaris, poses an intellectual challenge, playing with material far more dangerous because it is so close to the mainstream of Islam. The Ismailis had an avowedly new program, claiming esoteric knowledge; the unique knowledge ISIS claims is of the true version of the faith Muslims already hold.

To put it simply, in the great contest between the Assassins and Nooradeen az-Zangi—of whom ISIS’s founder, Abu Musab az-Zarqawi, was a tremendous admirer—ISIS claims to be the successor to Nooradeen, not the Assassins, intending to complete his project of uniting the Muslims by holy war, crushing the local heretics, and expelling the foreign infidels. The task is to have ISIS seen as the Assassins were, as a menace to Islam, rather than a vanguard of Sunni interests. Unfortunately, our own current policy is ratifying ISIS’s claim to be the defender of Sunnis against sectarian persecution and worse.

Pingback: Islam’s First Terrorists, Part 1 | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Islam’s First Terrorists, Part 2 | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Islam’s First Terrorists, Part 3 | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Islam’s First Terrorists, Part 4 | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Islam’s First Terrorists, Part 6 | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Islam’s First Terrorists, Part 5 | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: A Rebel Crime and Western Lessons in Syria | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Inaugural Address of the Islamic State’s New Spokesman | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Islamic State Spokesman Calls For Attacks Against the West | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Ideologue Laments A Jihadist Joining the Islamic State | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Meanwhile, On Other Fronts … | Not My First Rodeo

Pingback: Who Are The Khawarij? | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: ISIS’s Spokesman Denounces Al-Qaeda’s Leader, Claims ISIS Is The Victim | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Al-Qaeda Aligned Jihadist in Syria Condemns Rebel Group Jaysh al-Islam | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: America Reveals How Iran Funds Instability in Yemen | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Islamic State’s First Leader Explains How to Deal With Enemies | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Who Are The Khawarij? | Kyle Orton's Blog