By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on January 23, 2016

War cemetery in Sarajevo (personal photograph, July 2011)

It was announced on Thursday that Guantanamo inmates Tariq Mahmoud Ahmed as-Sawah and Abd al-Aziz Abduh Abdallah Ali as-Suwaydi had been transferred to Bosnia and Montenegro respectively. Sawah’s path to jihadi-Salafism allows a window into the Bosnian jihad, a much-underestimated factor in shaping al-Qaeda, its offshoots, and the wider jihadist movement. In that story is an examination of the role certain States have played in funding and otherwise helping the jihadists. It also leaves some questions about whether emptying Guantanamo of its dangerous inhabitants is the correct policy.

Early Life

Tariq as-Sawah from his Guantanamo file, 2008

Sawah is an Egyptian who was arrested in Afghanistan in late 2001 and is an “admitted member of al-Qaida,” according to a leaked assessment by the Joint Task Force Guantanamo (JTF-GTMO) from 2008. The JTF-GTMO document gives a rough biography of Sawah.

Sawah became a member of the Muslim Brotherhood at his high school in Alexandria, from which he graduated in 1975. Between 1975 and 1981, Sawah attended Alexandria University and attained a Bachelor of Science degree in Geology.

In late 1981, Sawah was arrested in the dragnet that followed the assassination of Egypt’s ruler, Anwar Sadat, by a hit squad led by Khalid Islambouli. (Interestingly, Khalid’s younger brother, Mohammed, has recently shown up as the probable leader of the “Khorasan Group”.)

Released in 1982, Sawah earned a teaching degree from al-Azhar and became a construction supervisor. In 1985, Sawah took a job in textiles and between 1986 and 1990 worked as an accountant. In 1990, Sawah moved to Greece as a private contractor in construction.

Saudi “Charities”

In early 1992, Sawah moved to Zagreb, Croatia, and began work for the “World Islamic Relief Foundation,” the JTF-GTMO file says, which likely refers to the International Islamic Relief Organization (IIRO). This was Sawah’s entry into the Bosnian jihad.

IIRO is an ostensible charity but was in fact tied into a web of groups—called “Allah’s NGOs” by some—that supported jihadism in Bosnia in the early 1990s. With the siege of Sarajevo in place and this being early in the war, entry routes into Bosnia were not easy, writes John Schindler in Unholy Terror. “Zagreb quickly became the ‘main Muslim supply center’ where, within a year, twenty Islamic organizations, including MAK, established offices to support the jihad by getting men and munitions into Bosnia through Croatia.” MAK is Makhtab al-Khidamat (The Services Bureau), the organization founded by Abdullah Azzam to supply foreign holy warriors against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan that evolved into the core of Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda after Azzam was killed in 1989.

Schindler writes that IIRO and its parent organization, the Muslim World League (MWL), which also operated in Bosnia, were both created and funded by the Saudi government as dawa (missionary) organizations, spreading Wahhabism, and were both entangled in “The Golden Chain,” the network of al-Qaeda’s chief donors in the late 1980s. Testifying in court in 1999, the head of IIRO in Canada noted: “The Muslim World League, which is the mother of IIRO, is a fully government funded organization. In other words, I work for the government of Saudi Arabia.” The qualification to be added here is that the nature of the Saudi system means most of its citizens work in some form for or with the government.

MWL was also the overseer of al-Haramayn Foundation, another Saudi-backed enterprise, and its specifically Bosnian branch, al-Haramayn al-Masjid al-Aqsa, both entities later added to the terrorism list. The Muwafaq (Blessed Relief) Foundation was also active in Bosnia and was listed by Bin Laden as a group he supported. Muwafaq did draw on Saudi State support, but its principal financier was the Jeddah-based businessman Yasin al-Qadi; both Muwafaq and al-Qadi were designated as terrorists by the U.S. in October 2001.

Before the end of September 2001, NATO forces in Bosnia raided the Sarajevo offices of the Saudi High Commission for Relief of Bosnia-Hercegovina (SHC), a charity founded in 1993 by then-Prince Salman (now King) and supported by then-King Fahd. Shortly thereafter, a cell of jihadists, the “Algerian Six,” was rolled up. One of six arrested men, Sabir Mahfouz Lahmar, had been paid by al-Haramayn and was serving (p. 284) as an administrator at SHC’s complex, a building costing $9 million and containing a mosque that can host 5,000 people. Lahmar had been arrested (p. 266) in October 1997, while working as a librarian at SHC, on charges of plotting to blow up the American Embassy in Sarajevo, and was convicted (p. 284) the next year of three violent crimes, including attacking a U.S. military advisor. The ringleader of the Algerian cell, Bensayah Belkacem, had arrived (p. 283) in Bosnia in late 1995, been naturalized in January 1996, and was found to be in phone contact with Bin Laden after 9/11. The intercepts from these calls led to a three-day lockdown on diplomatic facilities and hotels in Sarajevo starting September 17, 2001, and between September 25 and 27 a series of raids led by the British SAS brought the Algerians into custody.

The raid on SHC found before-and-after pictures of al-Qaeda’s attacks on the African Embassies, the U.S.S. Cole, and the World Trade Centre, documents of handwritten minutes (on IIRO and MWL letterhead) of meetings with Bin Laden, plus computer files on the use of crop duster aircraft, how to fake State Department badges, and antisemitic and anti-American propaganda materials aimed at children. SHC distributed at least $500 million (p. 129) in Bosnia during the war, ostensibly to mosques, cultural centres, schools, and orphanages, but SHC money also went to the Third World Relief Agency, which directly financed radical battalions (see below), and was geared more toward proselytization for Wahhabism than charity in post-war Bosnia.

Egyptian Islamism in Bosnia

Egypt had exerted a lot of influence over Muslim extremist circles in Bosnia and it was Egyptians who dominated the foreign jihadist scene in Bosnia during the civil war.

Amin al-Husseini surveying the Handzar Division, November 1943

As Schindler lays out in Unholy Terror (pp. 32-34), one of the most important Bosnian extremist groups is the Young Muslims, founded in March 1941. The Nazi occupation of Jugoslavija subdued Bosnia through a puppet regime run by the Ustaše, a zealously Catholic, hyper-nationalist Croat group, one of whose stranger beliefs was that Muslim Croats were “the purest Croats” (p. 33). A lot of space was given—at least symbolically—to Islam. When the SS began recruiting a Muslim division, the Handžar, in early 1943, it split the Young Muslims: some chose to join Tito’s Partisans, but the bulk chose to join Handžar, including Alija Izetbegović, Bosnia’s post-independence and wartime president. Amin al-Husseini, the infamous pro-Nazi Mufti of Jerusalem, visited the Handžar Division in April 1943 and called for more Muslims to join it.

Izetbegović was imprisoned (p. 39) in April 1946 for Islamist activities in Communist Jugoslavija—which took him out of harm’s way during the major crackdown on the Young Muslims in 1949, which among other things used their wartime collaboration to impose lengthy sentences on the group’s leaders, putting the group into effective dormancy. Upon release, Izetbegović returned (p. 40) to Islamist activism and under his direction the Young Muslims, in the 1950s, re-established links with the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt. Hasan Nasser, one of the conspirators in the Sadat assassination, even took refuge in Bosnia.

The Brotherhood’s ideas were smuggled into Bosnia through books and sermons. The Jugoslav Islamists also developed relations (p. 44) with the Sudanese Brothers, who would seize power under Hassan at-Turabi in 1989, and also the Syrian Brothers, including Mahmud Wadeh, who was struck down by Assad’s mukhabarat in Belgrade in 1981. Large parts of the Syrian Brethren fled to Europe after the Hama atrocity in 1982.

Alija Izetbegovic

As the tide of political Islam rose in the 1970s, Belgrade’s response (p. 44) was confused and largely hands-off, but UDBA drew a line for the Young Muslims when Izetbegović, using Tawfiq Velagić to give him “deniability,” made contact with the Embassy of the newly installed Iranian revolution. Izetbegović was arrested (p. 45) in 1983, charged with terrorism and collaborating with foreign enemies of the State, having apparently made a secret trip to Iran that year, and sentenced to fourteen years in prison, later reduced to twelve. “[T]o most Bosnians the [trial] seemed like a time warp,” Schindler writes. “The public had heard little mention of the Young Muslims in decades, and as far as Bosnians were aware the group had ceased to exist long ago.” At the trial, Izetbegović’s 1970 manifesto, Islamic Declaration, a pan-Islamist tract clearly influenced by the Brotherhood but which includes some phrasing about democracy, had been a chief part of the prosecution’s case.

In the course of events, Izetbegović was released from Foča prison in a pardon in October 1988. As Jugoslavija faltered, it was the old Young Muslim hands who founded the Party of Democratic Action (SDA), which inherited Bosnia from Tito and which is Bosnia’s governing party to this day. One of the SDA’s major funders during the war was Fatih al-Hasanayn, through his Vienna-based Third World Relief Agency (TWRA), which was tied into the support system of “Allah’s NGOs”. Al-Hasanayn, a Sudanese Islamist close to at-Turabi, had developed (p. 148) relations with Izetbegović when al-Hasanayn studied medicine in Belgrade and Sarajevo in the 1970s, and was among those who planned the security structures, notably the Muslim Intelligence Service (MOS), by which SDA secured its hegemony over the Bosnian State.

The old connections between Bosnia’s Islamists and Egypt became manifest once the war was underway. As Vahid Brown explains:

The conflicts in Bosnia and Algeria were intertwined by shared logistics networks, through which these two jihadi hotspots were also linked to another node of jihadi violence: Egypt. The Egyptian revolutionary groups—the EIG [al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya] and EIJ [Egyptian Islamic Jihad]—quickly established their presence in Bosnia, and their cadres were predominant among the leadership of the foreign mujahidin in Bosnia, as well as of the aid groups established to distribute and administer the influx of material support. The GIA [Groupe Islamique Armé from Algeria] was also prominently represented in Bosnia, especially among the rank‐and‐file volunteers.

Izetbegović was closely allied with fighters loyal to Omar Abdel-Rahman (“The Blind Sheikh”), the man accused of being EIG’s leader who was prosecuted over the 1993 World Trade Centre bombing. Izetbegović appeared (p. 55) in “grip-and-grin” promotional videos with Abdel-Rahman’s associates—and Bin Laden’s.

It was through extended networks associated with the U.S.-based Abdel-Rahman—notably the Muslim American Council, run by Abdurahman Alamoudi, who regularly supplied (p. 56) $5,000 payments to Abdel-Rahman from Bin Laden—that Izetbegović sought to lobby both the U.S. media and government.

The SDA’s effort to shape the media coverage was particularly important. There was much truth in the prevailing coverage of largely-Muslim victims of a campaign, directed from Belgrade, of ethno-religious expulsion, but significant complexities got less attention than objective coverage would have warranted. The atrocities by the “Muslim” side were often played down, for example, and very rarely mentioned was the alarming evidence that the SDA was behind some of the most iconic attacks in Sarajevo, including the May 27, 1992, “breadline massacre” against Muslim civilians and the July 17, 1992, mortar salvo as British Foreign Secretary Douglas Hurd met Izetbegović. The deputising by the Bosnian government in places, particularly Sarajevo, of distinctly unpleasant criminal elements, which preyed on “their own” more than they fought with the Serbs, was almost wholly uncovered. Likewise, the presence of the jihadi-Salafists, Iran’s involvement, and above all Sarajevo’s alliance with both got short shrift in the coverage.

EIJ was at this time led by Ayman az-Zawahiri, al-Qaeda’s current leader. Shattered in their home country and on the run, EIJ and Zawahiri found Bosnia as a cause and base, and Zawahiri was operating as Bin Laden’s deputy and a roving emissary as al-Qaeda cohered into a global network in the early 1990s. Zawahiri frequently visited Bosnia, tending the camps and distributing cash (Zawahiri’s brother Muhammad was al-Qaeda’s resident representative in the Balkans, working in several countries as an IIRO official).

Bin Laden himself visited Bosnia, being received as a personal guest of Izetbegović. Der Spiegel’s Renate Flottau recalls (p. 247) meeting Bin Laden in 1994 in the foyer outside Izetbegović’s office, where he was treated like a dignitary. Bin Laden handed Flottau a card with his name on it, but at the time it “meant nothing” to Flottau—this was before the Embassy bombings in 1998, when al-Qaeda was put on the international terrorist map—and they chatted amiably in English. Izetbegović’s staff were visibly displeased at Bin Laden speaking to a Western journalist. Eve-Ann Prentice of The Times, who was in the anteroom with Flottau, confirmed Flottau’s account, placing the meeting in November 1994.

Iran, al-Qaeda, and the SDA

Zawahiri and Iran had a long relationship of mutual admiration back to the 1980s. In Bosnia in the 1990s, Iran supported some of the same networks as al-Qaeda and is even said to have had a close working relationship with Zawahiri through Imad Mughniyeh, Hizballah’s military chief who was a fully commissioned officer (p. 30) of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Hizballah’s military trainers were thick on the ground in Bosnia—according to none other than its secretary-general, Hassan Nasrallah, whose statements to this effect, encouraging others to join them, were found (p. 149) among the possessions of an American Hizballah member.

It was Mughniyeh who personally met with Bin Laden in Khartoum around 1992 to seal the agreement Iran had made with al-Qaeda to cooperate in anti-American attacks—an agreement that ultimately led inter alia to Khobar Towers. Mughniyeh trained al-Qaeda operatives in camps in the Bekaa Valley, the 9/11 Commission Report notes (p. 61), and it was Mughniyeh among other Iranian agents who met with Zawahiri and other Sunni jihadists in Bosnia in a series of meetings where they agreed to coordinate support for the SDA government. The final wartime meeting took place in April 1995 in Khartoum. Iran’s “secret deal” with al-Qaeda continues to the present, facilitating al-Qaeda fighters getting to Syria.

Izetbegović held the Iranian revolution in high regard, as did many Islamists, for successfully bringing Islamist governance into reality. One appearance of this fact was during the preparation for Bosnia’s first post-Communism Election, on September 15, 1990. A large SDA rally was held at Velika Kladuša, comprising well over 200,000 people. Adil Zulfikarpašić, an ex-Communist who had become devout while maintaining his secularism, had helped financially in the founding of the SDA and now finally returned from his long exile (pp. 15-16) in Switzerland. Zulfikarpašić was horrified (p. 16): in the crowd were chants of, “Long Live Saddam Hussein,” and large pictures of the recently-deceased Ruhollah Khomeini. “By God, Alija, why are you doing this? Don’t you know that in a half an hour, these pictures will be shown around the world?” Zulfikarpašić asked Izetbegović on the stage. Zulfikarpašić broke with Izetbegović soon after and formed the Muslim Bosniak Organization.

One of Izetbegović’s first trips abroad as he prepared for the Elections that would formally undo Communism in Jugoslavija was to Iran in May 1991. It is said (p. 54) that then-Iranian president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani offered Izetbegović a blank cheque for what many knew was an impending war. True or not, during the war Iran shipped a huge amount of military hardware into Bosnia.

In April 1994, President Clinton gave a green light for Tehran to violate what was an unjust arms embargo, which did not serve humanitarian needs but locked in the imbalance between Sarajevo and the regime in Belgrade that had taken control of the old Federal Army, and to supply the Bosnian government with arms. That, Tehran did, but the Islamic Republic also began laying its own infrastructure to remain in the Balkans long after the war

Detailed intelligence from the CIA found:

Within weeks of Clinton’s decision to sanction Iranian arms shipments … hundreds of Iranian Revolutionary Guard fighters and trainers poured into [Bosnia], doubling the Iranian-sponsored presence to 400 or more. Two weeks after the green light was given, United Nations peacekeepers for the first time detected an independently commanded Iranian Revolutionary Guard unit on the ground in Bosnia.

And just 10 days after the green light, Iran appointed its first ambassador to Bosnia, Mohammed Taherian, who had served as Iran’s ambassador to Afghanistan when Iran was funneling aid and arms to the Afghan rebels [during the war with the Soviets in the 1980s].

Between May 1994 and December 1996, Iran sent (p. 138) 14,000 tons of weapons to the Bosnian government, which were worth anything up to $200 million. After the war, the SDA admitted to receiving $500,000 in cash from Iran, though Izetbegović denied that any of Tehran’s money had gone towards his re-election campaign in September 1996.

When an Iranian official said recently of Iraq that the current policy is “very similar to what happened in Bosnia,” where Iran was “fighting on the ground … while the airstrikes [were provided] by the United States,” he’s not wrong. Bosnia was America’s first attempt to make Iran a partner in regional security; it did not end well.

Nedžad Ugljen

Iran thoroughly penetrated the Bosnian security sector, and oversaw its most vicious units, notably the Ševe (Larks), the SDA’s shadowy paramilitary squad, responsible for “wetwork” (political assassinations) and a number of other atrocities.

Schindler documents that the idea for the Larks, which were created (p. 172) in May 1992, seems to have come from the circle around Fikret Muslimović, a career intelligence official with the KOS, the Counterintelligence Service of the Tito regime, who made his name in the 1980s as a warrior against the Islamist opposition (p. 156). Muslimović, while not involved in the very earliest stages of the SDA’s war-planning, soon offered his services in the spring of 1992 after an abrupt conversion to political Islam. Many doubted (and doubt) Muslimović’s sincerity, and rumours abound that he was agent of the KOS that Slobodan Milošević inherited in Belgrade, but Izetbegović welcomed him and the president had the final word (p. 157).

Muslimović and his deputy, Enver Mujezinović, a senior KOS officer who moved seamlessly into MOS, recruited snipers to the Larks, notably pre-war championship sharpshooters, Slobodan Šakotić and his sister, Slobodanka, and another pair of siblings, Dragan and Josip Božić—none of them Muslims, a deliberate choice to reduce their inhibitions when given orders by Sarajevo (p. 172). Another founding member of the Larks was Nedžad Herenda, one of its most prolific killers. The operational leader of the Larks was Nedžad Ugljen (a.k.a. “Necko”), a career intelligence officer in the Bosnian state, who was an agent of Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence, better-known as VEVAK (p. 244). In June 1994, a select cadre of the Larks led by Bakir Alispahić, a former Interior Minister and a then-senior spy in Sarajevo, were sent to Iran for training by the IRGC—in ideological matters, as well as the use of firearms and explosives—and returned to Bosnia on September 12, 1994.

Juka Prazina

The Larks, among other things, tried to kill (p. 174) the chief of the General Staff, Sefer Halilović, in October 1993, after he turned on the SDA for its corruption and extremism, and succeeded in December 1993 in killing Jusuf Prazina (a.k.a. “Juka”) in Belgium, a mafioso since the 1980s who had been made head of the Bosnian special forces until he broke with the SDA. The Larks, specifically Dragan Božić, was responsible for one of the most iconic crimes of the Bosnian War, the murder of “Sarajevo’s Romeo and Juliet”—a 25-year-old couple, Admira Ismić (a Muslim) and her boyfriend Boško Brkić (a Serb)—on the Vrbanja bridge, as they tried to flee the besieged city, on May 19, 1993. At the time the murder of Ismić and Brkić was blamed on the Serbian Orthodox forces of Ratko Mladić, as was the May 1995 killing of a French soldier under United Nations colours in front of the Holiday Inn that was in fact orchestrated by Herenda.

The Larks crimes were not just against other Muslims, and the Serb and Croat forces they were fighting. In late 1995, the CIA sent a station chief to Sarajevo, “H.K. Roy,” who had liaised with Ugljen. Ugljen wasted no time giving up “Roy” to his Iranian masters. Iran was in the planning stages (pp. 240-1) of a kidnap and murder hit when “Roy” narrowly escaped.

In January 1996, Izetbegović had founded the Agency for Investigation and Documentation (AID) as a secret police force reporting directly to him. AID was a part-reorganization, part-formalization of some wartime structures. Notably, AID was all-Muslim, a violation of the Dayton Accords. Alispahić led AID and Ugljen was his deputy; both men were extremely close to Tehran and AID functioned as an appendage of VEVAK.

The SDA-VEVAK coziness was disrupted after NATO troops from America, Britain, and France raided a ski chalet at Pogorelica near Fojnica, twenty miles northwest of Sarajevo, on February 15, 1996. What NATO found was: a training camp run by VEVAK officers, three of whom were arrested (one was released immediately because he was on a diplomatic passport), lists of Interior Ministry officials who had passed through the camp, racks of high-powered firearms, toy cars and shampoo bottles that were actually bombs, and a training model for assassinations. NATO believed attacks on its forces were being planned at Pogorelica. The SDA protested the raid. Pogorelica was training “special anti-terror units … to arrest war criminals,” the Bosnian government said. Izetbegović told NATO it was “an old training activity” that “was in fact being closed down” and all those arrested were there “to remove all the equipment.” This was a first admission of any cooperation between Sarajevo and foreign Islamist forces, but there was also an insistence that this only happened between 1993 and 1995 and that all foreigners had now left.

The Pogorelica raid had uncovered AID and the close links between its director, Alispahić, and Iran. Soon Alispahić, who also had links to the Larks, was fired and replaced with Kemal Ademović, who was less close to the Iranians (p. 244). Other senior AID officials with flagrant Iran ties, such as Irfan Ljevaković, were demoted (p. 244). Alispahić, Ljevaković, and Mujezinović are said to have been the driving forces behind AID; Mujezinović was also an Iranian asset. The Deputy Defence Minister, Hasan Čengić, a key mover of the Iranian arms shipments during the war who later ended up on a U.S. Treasury blacklist, was also fired.

After Pogorelica, Izetbegović needed “distance” from Iran to politically appease the Americans, making Ugljen a liability. Ugljen could not just be fired or demoted, however. Seeing the writing on the wall in the spring of 1996 (p. 244-46), Ugljen reached out to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) to offer them information on the SDA government’s criminality—about which he knew everything. Ugljen had been involved with Iranian intelligence, the Larks, the internal assassinations, the staged war crimes, and al-Qaeda. Ugljen had served as the contact point between Sarajevo and Enaam Arnaout (Abu Mahmud), a Syrian-American jihadist who ran the Benevolence International Foundation “charity”. When Arnaout was kidnapped by rival mujahideen, it was Ugljen who got him released (p. 244) and Ugljen who secured a Bosnian passport for Arnaout. Ugljen knew the end was near after Herenda, his comrade from the Larks who was now a member of AID, was arrested on June 25, 1996, by AID itself (p. 244-45). Ademović, at the head of AID, was trying to clear house, if only to get operations working again, since the Bosnian intelligence system had become such a mess of politicised corruption. Under torture (p. 245), Herenda confessed everything: his senior role in the Larks under the guidance of a small clique of SDA officials and Muslimović’s loyalists in the military and police; the killing of Muslim civilians and the attempted assassination of General Sefer Halilović; the secret efforts to terrorise non-Muslim populations into leaving Sarajevo; and the smuggling and drug-dealing in which the Larks were involved. Horrifically beaten and shot, Herenda was dumped on the roadside on June 29, 1996—and miraculously survived, fleeing the country to tell his tale abroad. (An AID officer, Edin Garaplija, was convicted in 1997 and sentenced to 13 years for Herenda’s abduction—despite testifying to having acted under Ademović’s orders.) On September 28, 1996, Ugljen was liquidated as he left his mistress’s apartment in Sarajevo by assailants never determined, preventing him testifying to The Hague tribunal, and closing the book on the SDA’s alliance with Iran and al-Qaeda for all but a few intrepid journalists in Bosnia.

Certainly the U.S. treated Ugljen’s demise as evidence that the SDA’s ugly wartime partnerships were at an end. The U.S. had made the reduction of Iranian influence in Bosnia a top priority of the NATO occupation. On June 26, 1996, President Clinton certified that all foreign fighters had left Bosnia—a key condition of the Dayton Accord. With the firing of officials flagrantly tied to the Iranians, specifically the removal of Čengić at the Defence Ministry, and the apparent exit of the Iranian-run foreign mujahideen, the U.S. released $100 million-worth of U.S. military aid to Bosnia in November 1996, with the Clinton administration’s public position being that Iran’s influence over the Sarajevo government was significantly diminished. But this was not what the CIA said. Izetbegović has been “co-opted by the Iranians” and is now “literally on their payroll,” according to a classified CIA analysis in late 1996, which further noted that Tehran had indeed bankrolled Izetbegović’s re-election in 1996 and, despite the fact Čengić had been removed, there was still at least one VEVAK agent in the Bosnian Cabinet.

Even as Iranian assets were supposedly being combed out of Sarajevo’s security system in early 1996, AID dispatched Iranian-trained commandos into Croatia to try to assassinate Fikret Abdić, a long-standing opponent of Izetbegović’s who had actually won the first post-independence election. (Abdić’s critics maintain that he was an agent of Milošević’s KOS.) Throughout the fall of 1996, as the Iranians’ visibility was being reduced in Sarajevo, Iran’s influence was spreading elsewhere: Tehran opened a new Consulate in Mostar, a radio station, cultural centre, two “reconstruction centres,” and a Red Crescent Society office. The Red Crescent especially is a known front for VEVAK and IRGC. Despite occasional setbacks, Iran’s meddling in Bosnia continues to the present.

Joining the Bosnian Jihad

In 1993, Sawah “joined the 3rd Bosnian Army and fought in the Bosnian war for three years,” his Guantanamo file says. While Sawah’s activities between 1996 and 1999 are unclear, it is apparent that he remained in Bosnia during this period. This is a well-established pattern for foreign mujahideen who made their way to Bosnia during the war.

Between 4,000 and 6,000 foreign jihadi-Salafists joined the war on the SDA government’s side, with about 3,000 Bosnians also fighting in the mujahideen detachments rather than as part of the regular army. The crucial organizer of the foreign fighters in Bosnia was the above-mentioned MOS, which had “direct links with al-Qa’ida and bin Laden’s inner circle from the war’s opening phase,” Schindler writes (p. 160). A key finance mechanism for this was the above-mentioned Benevolence International Foundation, one of “Allah’s NGOs,” which was tied to Bin Laden and MOS; another was TWRA.

The Seventh Muslim Brigade was formed in November 1992, bankrolled by TWRA, and recruited mostly local radicals, some of whom had fought in the Afghan jihad. Growing to a size of over 1,000 men and being under the direct command of the Third Corps of the Army of Bosnia-Hercegovina (ABiH), the Seventh Muslim Brigade was “the SDA’s flagship unit, the prototype of the Islamist fighting force Izetbegović’s army was supposed to become,” Schindler writes (p. 168). The Seventh Muslim Brigade was indeed as much a political project as it was a military one; military recruits were screened (p. 168) for “moral” purity and then subjected to intense politico-religious instruction/indoctrination by SDA-approved imams.

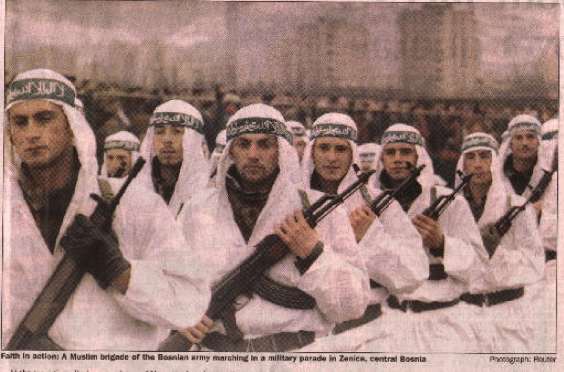

Seventh Muslim Brigade

Schindler documents (p. 169) two smaller units on a not-dissimilar model to the Seventh Muslim Brigade, the Ninth Muslim Liberation Brigade and the Fourth Muslim Light Brigade, which was formally founded in 1994 but which had existed in various forms since 1992 under the leadership of Nezim Halilović, a zealot preacher and Saudi favourite known as Muderis (a Qur’an teacher), who based himself in the enormous King Fahd Mosque after the war, attaining legendary status among Islamist radicals.

A group of “Afghan Arabs” and Albanian jihadists (some from Kosovo rather than Albania proper) revived (pp. 167-8) the Handžar Division, which, like its original, spent more time killing civilians, like the monks Nikola Miliciević and Mato Migić, rather than engaged in combat. The key foreign-dominated unit, though, was Odred el-Mudžahid (The Holy Warrior Detachment), founded in August 1993, which also served under the Third Corps—likely what is referred to Sawah’s Guantanamo file. El-Mudžahid were based around Zenica, where the Third Corps was headquartered, and some of their most infamous atrocities were committed in nearby Travnik. While most Islamist battalions were more interested in proselytization, el-Mudžahid did real fighting, suffering (pp. 74-5) 500 dead—400 of them foreign Arabs—and 2,000 wounded.

Izetbegović initially denied all knowledge of the jihadists, despite attending (p. 169) an el-Mudžahid camp as early as November 1993; then it was said that the jihadists were freelancers unconnected to official structures. Documents show el-Mudžahid registered (p. 167) as “Military Unit 5689” within ABiH and its leaders—including the most infamous of all, the young Algerian, Abdelkader Mokhtari, better known as Abu Maali—were paid and promoted as any regular soldier was. When it became impossible to deny that the mujahideen had been put under official sanction, it was said that this was done to try to get control of them—and the commander, General Enver Hadžihasanović, did seem to genuinely dislike the foreigners who paid him little heed. But as Hadžihasanović noted: “Behind [the mujahideen] there are some high-ranking politicians and religious leaders.”

Sawah “accepted the sponsorship of known al-Qaida associate Abu Maali,” according to the Guantanamo file, and “probably served under Maali when he fought in the Bosnian War, and reported he worked for Maali following the war.” Sawah also admitted that his unit in Bosnia was supplied with money and weapons by Khaled Sheikh Muhammad (KSM), the planner of the 9/11 atrocity, who personally visited Bosnia in 1995. Two of the “muscle hijackers” on American Airlines Flight 77, which smashed into the Pentagon, Nawaf al-Hazmi and Khalid al-Mihdhar, both Saudis, also fought with the mujahideen (p. 281) in Bosnia. Sawah met with KSM several times in Bosnia between 1995 and 1999, his Guantanamo file says, and also knew of KSM’s close links with Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn (Abu Zubaydah), who coordinated the movement of fighters from Afghanistan to Bosnia during the war.

After the signing of the Dayton Accords and the occupation of Bosnia by 60,000 NATO troops, the foreign jihadi-Salafists were supposed to have left by January 19, 1996, but there was a loophole: NATO could not very well insist on the expulsion of Bosnian citizens, so the Izetbegović government engaged in a mass-naturalization of mujahideen.

It is estimated that 12,000 Bosnian passports went missing during the war. According to Senad Avdić, editor-in-chief of Slobodna Bosna, an investigative weekly that has done much to expose official corruption and connections to Islamism, one of the passports went to Bin Laden (p. 282). (Avdić added: “If Bin Laden doesn’t have a Bosnian passport, then he has only himself to blame!”) KSM acquired Bosnian citizenship in November 1995. Some of the missing Bosnian passports were used to naturalize the mujahideen, at least 100 of whom had never even been in Bosnia, and some of those turned up in Afghanistan and Pakistan after the fall of the Taliban. This was the path Sawah took: moving to Taliban Afghanistan in 2000, Sawah’s Bosnian passport was found during the raid on al-Qaeda’s guesthouse in Karachi that netted Ramzi bin a-Shibh in September 2002, his Guantanamo file explains.

Taliban Afghanistan

Sawah left Bosnia in October 2000 and travelled—via Turkey and Iran—to Afghanistan, where he was initially arrested and interrogated by the Taliban for forty days, according to the JTF-GTMO dossier. Upon release, Sawah moved through a series of al-Qaeda camps, learning skills in urban warfare, mountain tactics, and mortars. Sawah admits to being an al-Qaeda member from this point, having gone to Afghanistan with the “express intent of supporting” Bin Laden, the JTF-GTMO document records.

The JTF-GTMO file goes on: After a trip to the front lines against the Northern Alliance, Sawah moved to al-Farouq Camp, near the airport in Kandahar, in May 2001, where he was taught about explosives by Mushin Musa Matwalli Atwa (Abdurrahman al-Muhajir), who built the bombs for the attack on the U.S. Embassy in Kenya in August 1998 and the attack on the U.S.S. Cole in October 2000. Having completed the two-month course in late June 2001, Sawah offered himself to Mohammed Atef (Abu Hafs al-Masri), al-Qaeda’s military chief and one of Bin Laden’s two deputies, the other being Zawahiri. Sawah’s name would show up on one of Atef’s databases of al-Qaeda members after Atef was killed in November 2001.

Between July and August 2001, the JTF-GTMO file records, Sawah taught at least two courses in bomb-making to a total of eighty students at Tarnak Farm, a facility also known as “Abu Ubaydah Camp,” located fifteen-to-twenty miles from the Kandahar airport and named for al-Qaeda’s first military emir, Ali Amin al-Rashidi (Abu Ubayda al-Panjshiri), who drowned in Lake Victoria in 1996. Sawah was proud of having been personally praised by Bin Laden for his “good work” teaching at Tarnak Farm, the JTF-GTMO docket notes. Sawah also had contact with Mahfouz Ould al-Walid (Abu Hafs al-Mauritani), Bin Laden’s religious adviser and al-Qaeda’s chief shar’i. Sawah recommended students he thought would be willing “martyrs,” and Sawah conferred with Midhat Morsi as-Sayid Umar (Abu Khabab al-Masri), a chemist and bomb-maker who was a key figure in al-Qaeda’s never-ending hunt for weapons of mass destruction, to pick out students for their explosives and poisons course.

In August 2001, al-Farouq was closed and at this time Sawah moved to Jalalabad, according to the leaked JTF-GTMO file. Sawah remained in Jalalabad until he was arrested on November 18, 2001, by the Northern Alliance after being injured by a cluster munition as he tried to cross into Pakistan at Tora Bora. Sawah was handed to the Americans in December 2001.

Sawah had developed, at the direct instruction of Muhammad Saladin Zaydan (Sayf al-Adel), Atef’s deputy on the military committee, specialized improvised explosive devices (IEDs). Sawah developed a prototype of the shoe bomb later used by Richard Reid and, after Sept. 11, worked on constructing limpet mines to attack American ships that Zaydan “assumed were heading to harbors in Pakistan.” Sawah designed and built four magnetic limpet mines, JTF-GTMO records. Sawah was also found to have “detailed information on chemical explosives, conventional and non-conventional weapons.”

The JTF-GTMO assessment says that Sawah knew in advance of al-Qaeda’s plot to kill Ahmad Shah Massoud, the charismatic leader of the Northern Alliance, just two days before 9/11. Additionally, Sawah “may have had prior knowledge” of the 9/11 massacre. Sawah’s above-mentioned connection to KSM might well have been deeper than he was willing to admit.

In Guantanamo

From 2004 onwards Sawah was extremely cooperative, the JTF-GTMO says, proving a “highly prolific source” who had “provided invaluable intelligence regarding explosives, al-Qaida, affiliated entities, and their activities”. That said, Sawah had proven in places only “partially truthful”—for instance, being very shady about the “details of his militant training and activities prior to his arrival in Afghanistan”—and Sawah was “careful to discuss the al-Qaida members instead of himself.”

Sawah was assessed at Guantanamo as a “Medium” risk to the U.S. and her interests. Sawah was “occasionally hostile to the guard force and staff earlier in his detention,” the JTF-GTMO file said, but his cooperation with the Americans made it unlikely he will be much trusted by his comrades on the outside.

Conclusion

The actions of the Izetbegović government, Iran, and Saudi Arabia during the Bosnian War made it an epicentre in shaping the jihadi-Salafist movement on the road to 9/11. Threads of the 7/7 atrocity (pp. 298-9) went through Bosnia and 9/11 itself had a Balkan dimension. The alumni of the Bosnian jihad continue to show up in terrorist activities, increasingly actually in Bosnia. These actions also imported a radicalism into Bosnia itself that had heretofore been marginal, but which now has deep local roots—enabled by a chronically weak State, large-scale corruption, and the continued activities of the intelligence services of the countries who imported the ideology in the first place. The leading role of the Saudis in rebuilding Bosnia—particularly the mosques, restored in Wahhabi-style whitewash rather than their ornate pre-war Ottoman style, and cultural centres—was especially damaging to Bosnian Islam. For all these reasons the Islamic State has not been without success in recruiting from Bosnia.

Sawah is a near-textbook example of the path taken by many of al-Qaeda’s pre-9/11 members, who worked in one of the active, “ABC” jihad theatres—Algeria, Bosnia, or Chechnya—on al-Qaeda’s dime, before moving to Taliban Afghanistan as those conflicts wound down. Al-Qaeda has now perfected its insurgent model in Syria, but it has—for all the talk of the “far enemy”—long been in the insurgency game. Up to 20,000 fighters were trained al-Qaeda camps between 1996 and 2001 in Taliban Afghanistan, according to the 9/11 Commission (p. 67), and al-Qaeda effectively used active combat zones as training theatres, into which it sent talent spotters to find people who could do terrorism further abroad.

The contest within the Bosnian State apparatus between the hardliners and those determined to root out the extremists and Iran’s spy-terrorist apparatus that stands behind so much of the militant activity goes on. The damage the Saudis have done in spreading extremism in Bosnia is incalculable. If there is any difference it is that after the internal insurgency in Saudi Arabia in 2003-04, the Saudis have rather redefined their definition of acceptable partners in foreign policy more in line with Western interests, while Iran remains a revolutionary government committed to the expulsion of the West from the Middle East and will work with terrorist groups, including al-Qaeda, to achieve that end.

The final issue is the detention facility at Guantanamo. Just over a week ago, the U.S. transferred ten Yemeni jihadists detained at Guantanamo to Oman, bringing the total population of the facility below 100 for the first time since 2002—to ninety-one, thirty-four of whom have been approved for transfer. Amnesty International released a statement saying that this was welcome but “this trickle of transfers should become a torrent”. There is reason to be sceptical that this is the best course of action, however.

In September 2015, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) reported that of 653 detainees who had been transferred, 196 were either confirmed (117) or suspected (79) of rejoining the jihad. That nearly a third of released Guantanamo detainees have rejoined Islamist terrorism undersells what has happened since many of the rest have remained committed ideologues who spread jihadist propaganda or otherwise facilitate the cause for which they were imprisoned in the first place.

The race to release the Guantanamo detainees is a political decision based on a calculation—that the immediate danger from releasing hardened terrorists is offset by narrative “strategic gains” against the jihadists’ recruitment propaganda—which is simply wrong. Guantanamo is not a key driver of radicalization and never has been, but the danger of releasing men with specialist skills back into the ranks of the jihadists during an ongoing war is pressing and immediate.

Post has been updated

Pingback: Another Legacy of the Bosnian Jihad | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Barack Obama Comes Clean | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Assad Cannot Keep Europe Safe From the Islamic State | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Passing of Hizballah’s Old Guard | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Al-Qaeda Marches on in Syria | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Dangers of Emptying Guantanamo | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Al-Qaeda in Syria and American Policy | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Al-Qaeda’s Leader Calls for Jihadi Unity in Syria, Building a Caliphate | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: An(other) Islamic State Terrorist Who Began in London: Abdullah al-Faisal | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: "Passing through Bulgaria, Iran is planting Hezbollah members in Balkans" | Vocal Europe

Pingback: Another Product of “Londonistan”: Abdullah Ibrahim al-Faisal | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Need for Caution in Releasing Guantanamo Inmates | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: America Reveals How Iran Funds Instability in Yemen | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The West’s Inconsistent Approach To Foreign Fighters in Syria | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Iran and Russia Are Using the Taliban Against the West | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Don’t Assume the Westminster Terrorist is a ‘Lone Wolf’ | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Coalition Targets Islamic State Recruiters and Terrorism Planners | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Al-Qaeda’s Deputy Killed in Syria | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Martyr for the Cause | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Legacy of Kofi Annan | Kyle Orton's Blog

Pingback: Another Legacy of the Bosnian Jihad | Kyle Orton's Blog

Pingback: The Jihad Factor in Bosnia | Kyle Orton's Blog

Pingback: Bosnian General Convicted for Jihadist Crimes | Kyle Orton's Blog

Pingback: Don’t Assume the Westminster Terrorist is a ‘Lone Wolf’ | Kyle Orton's Blog