By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on January 25, 2017

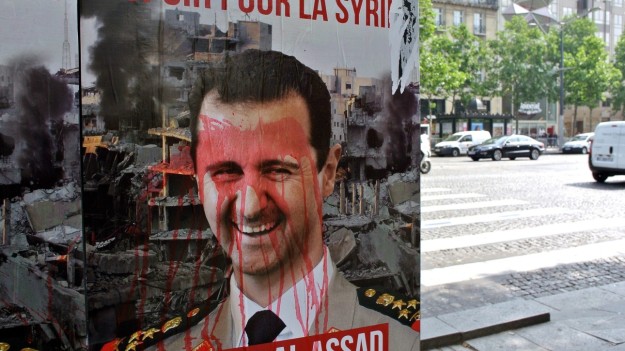

Syria has broken down as a functioning entity. There were some who saw in the takeover of Aleppo City last month by the coalition of states and militias that supports Bashar al-Assad’s regime the beginning of the end of the war. The pro-Assad coalition will make further territorial gains in 2017, but peace—even the peace of the graveyard—is still a long way off, and unlikely to ever arrive while Assad remains in power. The West, unwilling and apparently unable to remove him, nonetheless has vital interests in Syria that cannot be outsourced and must be secured by navigating a fragmented state.

EXTERNAL INTERVENTION KEEPS ASSAD STANDING, SYRIA IN TURMOIL

Twice in twenty-four months an outside power had to directly step in to rescue the regime of Bashar al-Assad.

With the insurgency making rapid gains at the end of 2012 and into early 2013, the Islamic Republic of Iran orchestrated a jihad that brought foreign Shi’a holy warriors from Afghanistan to the Ivory Coast into Syria to stave off regime collapse. Tehran reached its limit in early 2015.

By the summer of 2015, insurgents were again threatening the regime. Russia began its airstrikes that September, which stabilized the regime and weakened the mainstream opposition, continuing the regime’s attempt to leave terrorists to dominate the anti-Assad forces and thereby rehabilitate Assad internationally.

Russia quickly shifted the terms of the war so that it became doubtful that the revolution could achieve its strategic objective of deposing Assad by force, and with the fall of Aleppo City the rebels’ ability to bargain for a political transition that removes Assad now seems very unlikely. The situation could be changed by significant outside intervention, but that, too, seems unlikely at this stage. The war is far from over, however, and Assad’s survival will ensure it continues.

After Aleppo, there are nine significant areas outside regime control. There are the major rebel enclaves of “Greater Idlib,” East Ghuta, and the Southern Front, with minor pockets around Rastan and in Qalamun. There are then two non-revolutionary enclaves, where rebels are being used by Turkey in north-east Aleppo to protect the border and one held by U.S.- and Jordanian-backed anti-IS forces headquartered in al-Tanf. And finally there are the two alternate state-building projects, the Kurdish PYD/PKK in the north-east and the Islamic State (IS) in the east.

Battered and—in current circumstances—strategically neutralized, the rebellion nonetheless contains around 100,000 men, including 50,000 in eighty U.S.-vetted groups. Jabhat Fatah al-Sham (JFS), al-Qaeda’s Syrian branch, and its dependencies and fronts have no less than 15,000 fighters, mostly confined to Idlib. Beyond that there is the large-if-uncertain number of Islamic State (IS) jihadists.

The regime, though structurally weak, especially in terms of manpower, retains, as does Iran, the goal of re-establishing Assad’s writ across the whole country. There are some indications Russia’s position is “softer”. Assad’s forces and the Iran proxy militias have at times seemingly defied Russian guarantees to rebels. But with the Russians’ own record—obliterating an aid convoy in airstrikes over three hours, for example, when it had agreed to their safe-passage—whether Moscow is genuinely being thwarted or relying on the misbehaviour of allies is both impossible to say and irrelevant given the balance of forces.

This is a recipe for ongoing conflict.

WILL THE REGIME TARGET THE ISLAMIC STATE NEXT?

The current so-called peace talks in Astana are political cover for the pro-Assad coalition’s military strategy: it legitimizes the gains already made, allows limited warfare against key fronts to continue, and gives time to prepare the next round of aggression. Where that next round will occur is now the question.

IS has made clear its capacity to challenge the regime, taking Palmyra (again) the day before Aleppo was conquered and bringing intense pressure earlier this month against the regime’s pocket of territory in Deir Ezzor City. These offensives were not a surprise, but for two major reasons the pro-Assadists kept focus on Aleppo. One reason is the pro-regime coalition’s undisguised policy of deprioritizing IS until all workable oppositionists have been eliminated, leaving Assad as the lesser-evil. The other reason is that the regime coalition simply lacks the capacity to re-assert control over much of the territory currently occupied by IS, particularly Raqqa and Deir Ezzor.

Driven from its major urban centres, the insurgency has begun to shift to guerrilla warfare, a transformation that is a victory of sorts for the regime since it favours extremist groups within the insurgency that are prepared—morally and materially—to conduct car bombings and assassinations. This is a political defeat for the opposition, but the raw military calculation remains. If the regime coalition now sends resources east to retake Palmyra and/or buttress Deir Ezzor, it will provide space for insurgents, diminishing further the possibility of sustainably holding Aleppo City and perhaps even opening up areas further south like Homs. This is far from the “stability” promised by those who favour a regime “victory”.

These factors make it doubtful that IS will be the first target of the regime coalition this year. That said, Palmyra is politically important—this is what compelled the Russian-led operation to take it back last March—and there is perhaps a way the regime coalition can square the circle: gaining some assistance from the West. This has happened before.

The regime was informed by the Coalition, via Iran, that it had a security guarantee when the strikes began in Syria in 2014 and there were hints that the U.S. might countenance more direct assistance over Palmyra, justified by the U.S. as necessary measures to stop IS using captured material in U.S.-controlled battlespaces and to head-off external attacks. Indeed, in all the sound and fury over the accidental Coalition airstrike that killed regime soldiers in Deir Ezzor on 17 September, what got lost was the very strong suggestion that the Coalition had tried to provide close-air support to regime forces. The strike pattern in the month after Palmyra fell—more than thirty Coalition strikes in and around Palmyra—seems to bear this out, providing invaluable assistance to the pro-Assad forces.

WHY EAST GHUTA IS PROBABLY NEXT

Also unlikely immediate targets—pending some low-cost opportunity—are Rastan and Qalamun, which are quarantined and strategically unthreatening. Ditto the Tanf enclave, though the pro-Assad coalition did attack it in June, providing (again) a measure of air cover for IS.

The Southern Front is currently frozen by a tacit mutual understanding. When the pro-Assad coalition turns on the area, it will bring Iranian-controlled jihadists a stone’s throw from the borders of Jordan and Israel. Meanwhile, the rebels avoiding anti-regime action and being used by Jordan to guard the border is empowering jihadi-salafists who can claim the “revolutionary” mantle, and dismiss the Free Syrian Army-style rebels as hirelings of foreigners. The U.S. could act in advance of the crisis to, for once, shape the environment, while containing both Shi’a and Sunni jihadism if it bolstered the southern rebels and allowed them to engage in the struggle that defines them.

East Ghuta, where rebel-infighting has allowed the regime coalition to significantly shrink the besieged pocket, is the most likely candidate for the next target of the pro-Assad coalition. East Ghuta’s fall would secure the capital and more-or-less contiguous control of “useful Syria,” an area already subjected to significant demographic engineering, displacing hostile populations down to manageable levels and colonizing areas with pro-Assad constituencies.

THE CASE OF IDLIB

Idlib had seemed an even more promising target for the pro-regime coalition, albeit one that did not have to be rushed and thus would probably always have come after East Ghuta. As the regime coalition has liquidated the pockets of resistance in south and central Syria, it herded all of its enemies into Idlib, where JFS and like-minded groups are powerful. The clear hope was that the embittered people deported to Idlib would be recruited by the jihadists and the eventual campaign against Idlib could then be presented in War on Terror language, neutralizing the international outcry. But complications in that plan have appeared due to two factors, one internal and one external.

Internally, JFS was already testing the patience of inhabitants of Idlib and rather than the deportations from Aleppo providing angry foot-soldiers to JFS, the arrival of the activists and moderate rebels, who had dominated Aleppo City, led to horrified public statements about the combination of a lawless “jungle” and the “shari’a of power” that the jihadists had imposed on Idlib. The revolutionary elements were energized and the balance began tilting against the zealots in the province.

The external change is even more important, relating to Turkey’s change in priorities over the last year. Moving into Syria in August, a month after the coup attempt, Turkey’s Operation EUPHRATES SHIELD (OES) pushed IS away from the border and checked the maximalist ambitions of the Syrian PKK. It had also seemed like it might provide a potential wedge between the mainstream rebels and al-Qaeda by offering the rebels a better alternative.

It soon became clear that Turkey had coordinated with the Russians, and would make no move against the regime coalition. On the contrary. Turkey signed-off on the pro-Assad coalition taking over Aleppo City, even removing rebel troops from the area to fortify its border, and is now receiving the supporting airstrikes from Russia it was refused by the West in moving against IS-held al-Bab. Politically, Turkey seems—haltingly—to be moving toward the Russian position of a formal acceptance of Assad remaining and has, after long equivocation, begun referring to JFS as a terrorist organization.

Still, Turkey’s intervention did increase tensions between the rebels and JFS, which have now boiled over. The recent increase its Western airstrikes against JFS’s leadership is insufficient—and alone might be counterproductive—but if joined to bolstering rebels who are trying to assert control in their areas it just might work. Given the precedents, however, this chance to block al-Qaeda’s consolidation will likely be missed.

This leaves the regime coalition able to take advantage of the short-term disarray, or to move later, now with Turkey’s political posture toward JFS reinforcing its own. In short, the pro-Assad coalition will pocket Turkey’s political concessions and is happy to create a military dependency in a NATO state; whether Turkey can gain anything in turn—such as the protection of Idlib—time will tell.

THE KURDISH QUESTION

The PKK canton, enabled to expand, even into Arab areas, as part of the U.S.-led anti-IS war, is the wildcard. The PKK retains deep links with the pro-Assad coalition and its war against Turkey continues—the latter able to be intensified by the former if the Russia-Turkey rapprochement sours. And if it doesn’t sour, and if the pro-Assad coalition continues to advance, the PKK might find that its use to the pro-Assad coalition in keeping the Kurdish areas out of the revolution and sowing divisions among the rebels is at an end.

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

As can be seen from the foregoing, there is no one answer to what will happen or what should be done about Syria: it depends which area of the country one is talking about. Regime areas are a Russian-Iranian condominium and there seems little desire to challenge this. Southern Syria could be a zone of Western influence and nationalist, anti-jihadist ascendancy. North-western Syria could be on course to become a Turkish protectorate or the next victim of the pro-Assad coalition—or some combination. The Kurdish areas likely face war on one or more fronts in the coming period. Which leaves eastern Syria and IS.

Troubled as the Mosul operation has been, the Raqqa operation is in even worse shape. “No actor … has the ground force capability necessary to defeat all jihadists in Syria and keep them defeated. The trouble is, we’re really the only one that cares,” as Jennifer Cafarella of The Institute for the Study of War, put it to me. “That leaves us with two options: do it ourselves or beg, borrow, and steal local partners to do it for us.”

The U.S. refused to build up a rebel army that could police the Sunni areas IS seeks to rule, and allowed the fall of Aleppo City—despite its own assessment that this was a disaster for U.S. counterterrorism policy. Instead, the U.S. made the Syrian PKK its primary anti-IS instrument, despite the political complications this brings for the anti-IS coalition and the sheer military fact that the PKK cannot conquer all of the areas held by IS, which has meant boots on the ground—the avoidance of which was among the reasons for not helping the rebels earlier—were needed anyway.

Even on the heroic assumptions that the pro-Assad coalition does not involve itself in Raqqa as a political move to portray itself as a partner against terrorism, rather than the enabler it actually is, and Turkey does not put to use the many levers of influence it has against the PKK in Syria, an attack on Minbij most obviously, to undermine a PKK offensive in Raqqa, the U.S.-led operation will either leave the PKK in control of Raqqa or it will leave a weak Arab administration in control, and IS would gain space for a revival in both situations.

In a revolutionary war, the key is to ensure that military losses contain political victories that are useful over the long term, and in both Mosul and Raqqa there is every indication IS will get its wish. While on the defensive last time, IS’s emir, Hamid al-Zawi (Abu Umar al-Baghdadi), made a famous speech that conspicuously did not define success by territorial holdings. Rather, the purity of the IS movement’s belief, and the fact that “disbelief in all its forms … gathered against,” meant that it would “remain” (baqiya). IS points to the vindication of this prophecy as it prepares to retreat from its twin capitals back into the deserts, in al-Anbar and crucially in Deir Ezzor. This period of tribulation—which separates the hypocrites from the true believers—will pass, in IS’s telling, and victory will come, in god’s good time.

Ensuring that IS has no peace in the deserts this time and that legitimate local forces, rather than the PKK or Iran’s proxy militias moving in from Iraq after Mosul falls, displace IS and are protected over the long-term is the way to sustainably defeat IS. Such a protectorate might provide a refuge for the displaced, a way to halt the spill-over that is destabilizing and radicalizing Europe to Russia’s advantage, and—if there was the will—the territory to build a rebel government that could credibly sit across the table from the regime in all-Syrian negotiations that finally bring an end to this terrible war.

For now, however, the resolve and capacity to remove Assad appears to have deserted the West. The job therefore defaults to one of salvage in Syria. The war will continue for quite some time but there are areas of the country that the West can shape favourably, and symptomatic threats of this war like IS and al-Qaeda that must be combatted. This does not change the fact that Assad is the fons et origo of the conflict whose presence permanently destabilizes Syria. An infamous slogan at the outset of the war from pro-regime forces was, “Assad, or we burn the country”. As we can now see, with the dictator seemingly safe, the true descriptor of Syria’s fate is, “Assad and we burn the country”.

Originally published at The Henry Jackson Society

Pingback: The West Helped the Assad Regime and Its Allies Take Palmyra | Kyle Orton's Blog