By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 24 October 2024

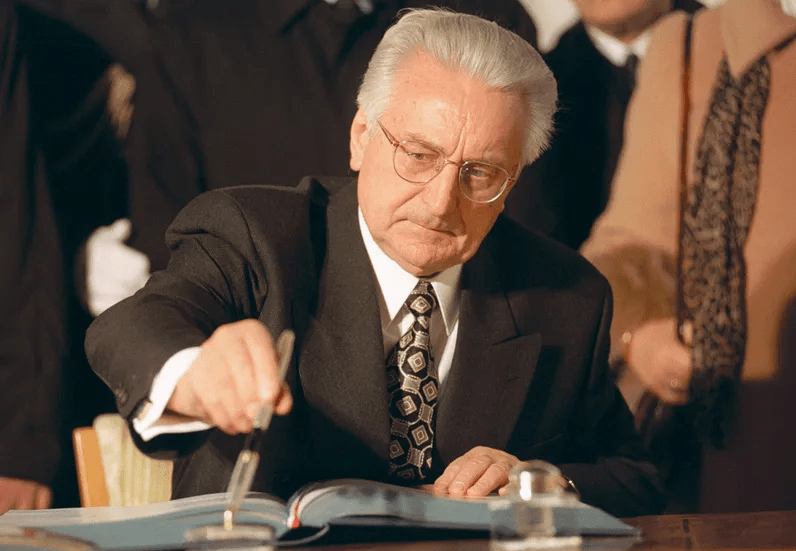

As Jugoslavija broke down and slid into war in the early 1990s, part of the political warfare between the parties was an effort by Serbia and Bosnia to portray Croatia’s president, Franjo Tuđman, as a “fascist”.

In August 1991, Serbian president Slobodan Milošević’s Counterintelligence Service (KOS) executed Operation LABRADOR, the false flag bombing of a Jewish community centre and cemetery in Zagreb, Croatia’s capital, combined with a disinformation campaign (Operation OPERA) to blame this on the Croatian government. Serbs and Muslims regularly referred to Croats as “Ustashis”, and this line of propaganda caught on in sections of the Western press, at least from late 1992, when the Bosnian Croats—under Tuđman’s firm control—started clashing with troops from the Bosnian Muslim government led by Alija Izetbegović.

As with all the best disinformation, the KOS was working with enough facts to make their narrative plausible.

Tuđman had been a Communist anti-Nazi Partisan during the war, a fact he would invoke later to shield himself against charges of antisemitism and fascist sympathies, and he served in the Communist military bureaucracy from 1945 until 1961, when he left at his own request and soon afterwards became a nationalist.

The problem Tuđman now faced was a very personal one of how to deal with the Second World War: Concluding Communism was a monstrosity, did that mean he had fought on the “wrong” side? Did that make the Nazi-dependent Ustaše’s “Independent State of Croatia” (NDH), the enemies he had fought, the “right” side, and was he willing to embrace their grisly record? Unable to satisfactorily answer those questions, Tuđman re-wrote the questions.

It is in this attempt—beginning thirty years before Jugoslavija collapsed—to formulate a Croatian nationalism that incorporated a palatable version of the NDH that we see the origins of Tuđman’s historical “revisionism”, which would become official doctrine under Tuđman’s rule of post-1990 Croatia. The advent of Serbian nationalist historical revisionists in the 1980s perhaps sharpened Tuđman’s revisionism, but it was not a reactive phenomenon.

Tuđman’s nationalism and historical revisionism were entwined from the get-go, the one supporting the other. In this, Tuđman and the Croats were far from unusual.

Nationalist identities are underwritten by a historiography of eternal blamelessness, the periods of war in their annals—even the ones they initiated—explained as defensive actions after prolonged indignity, injustice, and injury. “It is this logic”, notes Slobodan Drakulić, “that makes the history of nationalism read like a protracted litany of grievances coupled with acts of self-defence, often in the form of ‘first strikes’.” This mindset animated every side during the Balkan War of the 1990s.

It might be wondered why Tuđman did not just draw a veil over the NDH, and here, too, the answer is one common to all nationalisms since their emergence in the nineteenth century: nationalist historiography tries to push the existence of the nation-state it is seeking or has obtained as far back towards time immemorial as it can. It is a widespread human assumption even now that antiquity confers legitimacy, and if nationalist mythology is going to include fragmentary and shadowy references as evidence “the nation” is ancient, it can hardly ignore an actual nation-state formed by its kinsmen in living memory.

The result in Tuđman’s Croatia was an official revisionism that airbrushed the genocidal nature of the Ustaše and their role as wardens of a Nazi puppet State. Approved historiography emphasised the NDH as a Croatian State that protected its own people—meaning almost by definition the rehabilitation of symbols and leaders indelibly associated with the Nazi genocide in regime propaganda—while downplaying and denying the horrors the NDH inflicted on other peoples. Given this official discourse, it was relatively easy to portray Tuđman’s Croatia as the Ustaše reborn.

Slobodan Drakulić: “a protracted litany of grievances coupled with acts of self-defence” — a MOST interesting phrase, thank you.

The reportage about Gaza in Pakistan’s newspaper Dawn (which I’ve been following for 22 years) has been reading like that since a month or so after last year’s October 7th. Screaming, wailing, whining–the eternal child regarding the thing with glowing eyes and pulsating breath that’s lurking under his bed.

Matter of fact, on both sides of the street on this side of the pond, 99% of today’s political journalism (both news and opinion) is like that.

LikeLike