By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on August 24, 2015

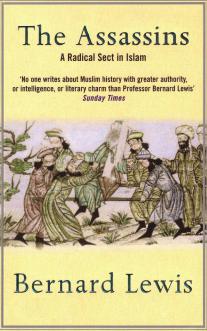

Book Review: The Assassins: A Radical Sect in Islam (1967) by Bernard Lewis

This review can be read in six parts: one, two, three, four, five, and six.

Abstract

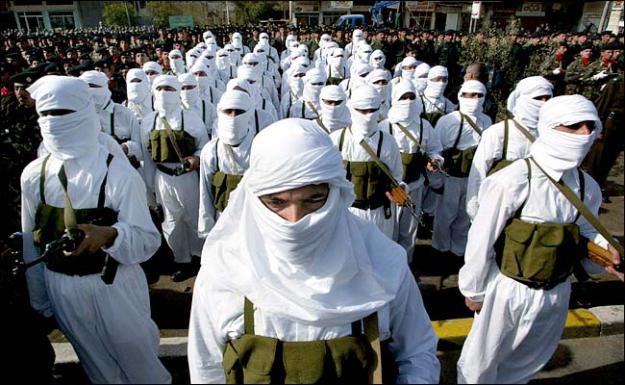

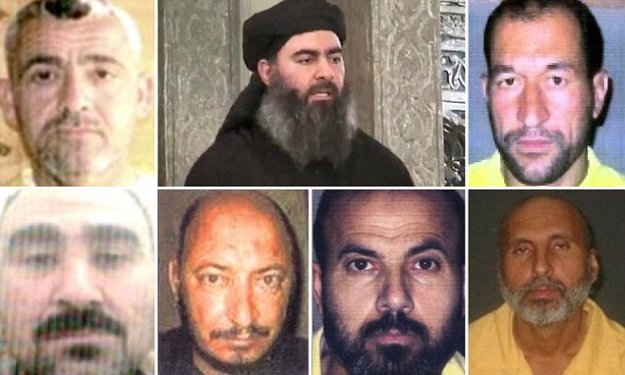

The fourth Caliph, Ali, was assassinated during a civil war that his supporters, Shi’atu Ali (Followers of Ali), lost to the Umayyads, who thereafter moved the capital to Damascus. The Shi’a maintained that the Caliphate should have been kept in the Prophet’s family; over time this faction evolved into a sect unto themselves, which largely functioned as an official opposition, maintaining its claim to the Caliphate, but doing little about it. Several ghulat (extremist) Shi’a movements emerged that did challenge the Caliphate. One of them was the Ismailis. Calling themselves the Fatimids, the Ismailis managed to set up a rival Caliphate in Cairo from the mid-tenth century until the early twelfth century that covered most of North Africa and western Syria. A radical splinter of the Ismailis, the Nizaris, broke with the Fatimids in the late eleventh century and for the next century-and-a-half waged a campaign of terror against the Sunni order from bases in Persia and then Syria. In the late thirteenth century the Nizaris were overwhelmed by the Mongols in Persia and by the Egyptian Mameluke dynasty which halted the Mongol invasion in Syria. The Syrian-based branch of the Nizaris became known as the Assassins, and attained legendary status in the West after they murdered several Crusader officials in the Levant. Attention has often turned back to the Assassins in the West when terrorist groups from the Middle East are in the news, but in the contemporary case of the Islamic State (ISIS) the lessons the Nizaris can provide are limited. Continue reading →

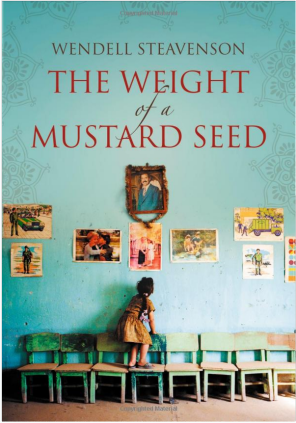

Book Review: The Weight of a Mustard Seed: The Intimate Life of an Iraqi Family During Thirty Years of Tyranny (2009) by Wendell Steavenson

Book Review: The Weight of a Mustard Seed: The Intimate Life of an Iraqi Family During Thirty Years of Tyranny (2009) by Wendell Steavenson