By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 16 November 2024

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 7 August 2023

Andrey Zhdanov was one of the key figures in the Soviet Great Terror (Yezhovshchina) and, indeed, during Stalin’s reign more generally until his death in 1948. Zhdanov is perhaps best remembered for the strictures he imposed on Soviet cultural life in 1946, known as Zhdanovism (or Zhdanovshchina).

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 6 August 2023

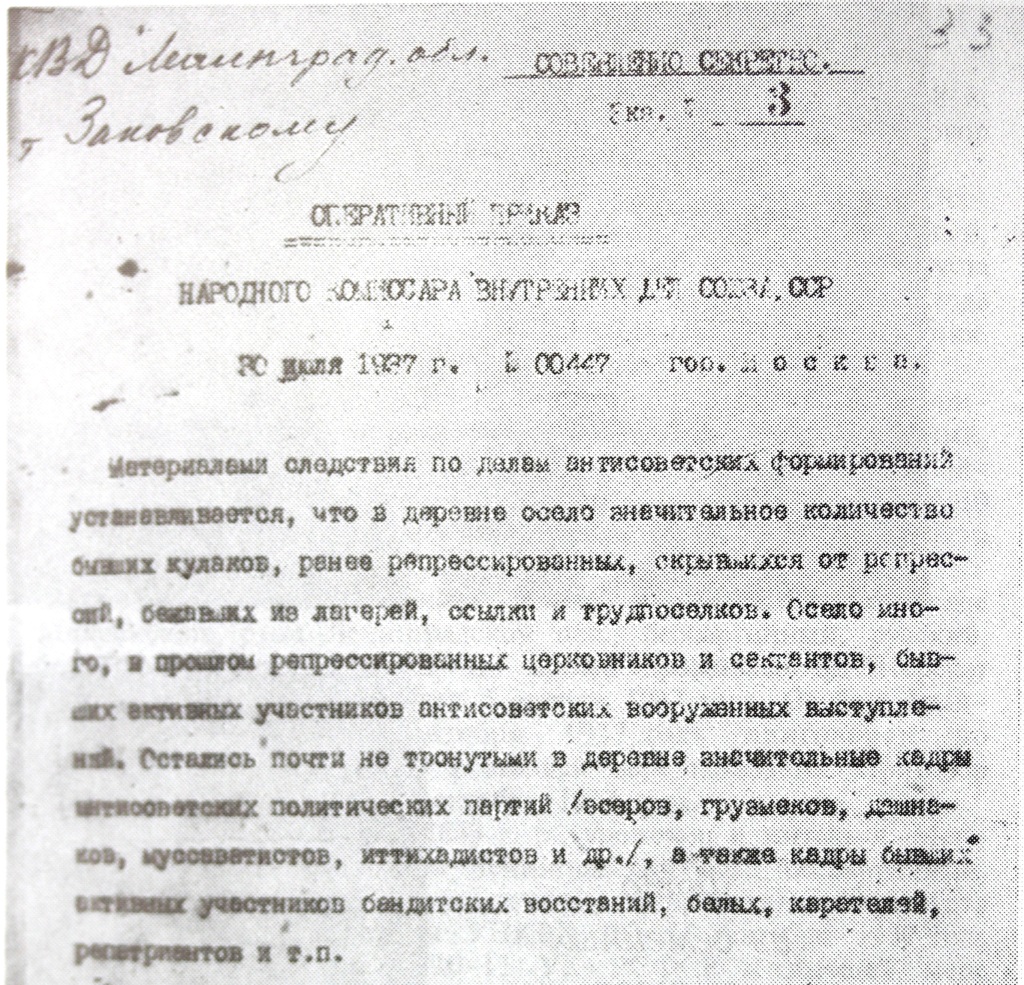

The head of the Soviet NKVD, Nikolai Yezhov, issued Prikaz (Order) Number 00447 on 30 July 1937, a secret instruction soon signed-off by Joseph Stalin, which vastly expanded the scope and scale of the Great Terror within the Soviet Union. The 2008 book, The Road to Terror: Stalin and the Self-Destruction of the Bolsheviks, 1932-1939, by J. Arch Getty and Oleg V. Naumov, as translated by Benjamin Sher, contains nearly the full text of the order (pp. 473-80), which is reproduced below.

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 10 December 2021

Michael Kellogg’s 2005 book, The Russian Roots of Nazism, argues that Russian “White émigrés” exerted financial, political-military, and ideological influences that “contributed extensively to the making of German National Socialism”. As such, argues Kellogg, Nazism “did not develop merely as a peculiarly German phenomenon”, but within an “international radical right milieu”. The book is interesting but deeply flawed, overstating its case by failing to set the facts it gathers in a proper context and for similar reasons misunderstanding where some of the Russian elements under discussion fit within the politics of the revolutionary upheaval after 1917, both within the borders of Russia and in exile in Europe. Continue reading