By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on May 23, 2015

To hear President Obama tell it, his announced program to defeat the Islamic State (ISIS), which began with airstrikes into Iraq last August that were extended into Syria in September, is working, albeit with some tactical setbacks. The implication is that the setbacks of the U.S.-led anti-ISIS campaign are not strategic.

As J.M. Berger phrased it:

In the Washington vernacular, the act of Being Strategic implies a near mystical quality of superior thinking possessed by some, and clearly lacking amongst the vulgarians of the world—heedless brutes such as ISIL. Tactics are short-term ploys, easy to dismiss. Strategy is for winners.

Unfortunately, this soothing view is almost exactly wrong: it is the United States that is relying on various short-term methods—commando raids into the Syrian desert, for example—while ISIS has a long-term goal fixed in mind and is working assiduously to achieve it. The U.S.-led Coalition is losing, in short, and ISIS is winning.

Yesterday, a Shi’a mosque in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province was struck by a suicide bomber, massacring more than thirty people. The attack was soon claimed by ISIS.

Last November, Abu Bakr al-Baghdad accepted the baya of ISIS branches outside Iraq and Syria: Libya, Egypt, Algeria, and (anonymously) Yemen and Saudi Arabia. The Libyan branch is the strongest, and getting stronger. Egypt’s ISIS branch is faring well and the conditions are in place for it to do better. Yemen’s ISIS branch has “come out” as Wilayat Sanaa, launched its first official attack in March, and is second only to Libya in its prospects. Now, after several minor attacks, ISIS in al-Saud also reveals itself; the attack was claimed by Wilayat Najd, an addition to Wilayat Bilad al-Haramayn, ISIS’ “provinces” in Saudi Arabia. The only ISIS branch that seems to have been wrapped up is in Algeria, but nobody should want Le Pouvoir in charge of counter-terrorism policy (see here and here).

In addition, ISIS has gained in Tunisia and Nigeria. Last December in Tunisia, a 97-second audio pledged allegiance to al-Baghdadi in the name of Jund al-Khalifa fi Tunis; nothing more was said about it. On May 18, a nine-minute audio gave baya to al-Baghdadi in the name of Mujahideen Tunis al-Qayrawan, and the announcement of an “official” wilayah (province) is believed to be imminent. And on March 7, Boko Haram declared its allegiance to ISIS, an addition (at least in propaganda terms) of 20,000 square-miles to the “Caliphate”.

To most it will be clear that this is not what it looks like when a group is being defeated, but the argument will be made that ISIS doesn’t really control these branches outside the Fertile Crescent, and therefore, in essence, there is no need to worry. The evidence against that is already quite convincing: direct emissaries of ISIS were sent to set up the branch in Libya and ISIS is in “full command and control” of the media operations of all of the branches whose baya it has accepted. The Saudi attack yesterday suggests this co-ordination is deeper still.

On May 14, al-Baghdadi released an audio statement that was taken by most as a proof-of-life statement after the wide reporting that al-Baghdadi had been injured in an airstrike on March 18. Credit for prescience has to go to Aaron Zelin for pointing out that the contents of the speech were actually the most important thing, namely a ferocious attack on Saudi Arabia for hypocritically acting against the Iran-backed Houthis in Yemen but doing nothing about Iran’s persecution of (Sunni) Muslims in Syria and beyond.

ISIS also released Dabiq 9 on May 21: the front cover was an attack on the Gulf regimes, and inside the magazine there were numerous attacks on Saudi Arabia, of which two stand out. First, ISIS again attacked the Saudis’ Yemeni operation by means of a condemnation of Faylaq a-Sham, a Syrian rebel unit of Muslim Brotherhood origins that declared solidarity with Saudi Arabia in this fight. “[W]hen the apostates (the Tawāghīt and the Rāfidah [Shi’ites]) fight each other, it is not permissible for the Muslim to support one,” Dabiq says. “[I]t is not permissible for the Muslim to fight against Āl Salūl [the House of Saud] under the leadership of the Rāfidī Houthis,” nor vice versa. And second, during a long condemnation of conspiracy theories—of all things—ISIS took serious exception to the insurgent gains in northern Syria, which have indeed been backed by the Saudis, Qataris, and Turks. “Āl Salūl have now openly occupied parts of Idlib, Halab, and Shām in general” through these Sahwa, said ISIS.

Not coincidentally, these two Saudi-led initiatives—the gains of insurgents in northern Syria and a pushback against Iran’s assets in Yemen—have done probably the most serious damage to ISIS’ public standing since the anti-ISIS Syrian rebel offensive in January 2014, and certainly more damage than the Coalition’s airstrikes. It has told the region, especially young Sunni men, that there is another way to resist Iranian hegemony. This has naturally upset ISIS since one of their main marketing tools is to present themselves as the sole defenders of Ahl al-Sunna, drawing in non-ideological recruits for practical reasons, who can then be radicalized into loyal footsoldiers.

The timing of the attack in Saudi Arabia is therefore suggestive of ISIS central leadership having direct coordination, if not command, capabilities with the ISIS branch in Arabia. In propaganda terms, ISIS can claim an ability to strike at its enemies anywhere—a projection of power being key to the momentum ISIS needs to survive.

Another central ISIS strategy is to polarize the politics of its enemies, accentuating differences and where possible pitting them against each other. The attack in Saudi Arabia also serves this purpose. If the Saudi monarchy condemns the attack on the Shi’a, it will be siding against Sunnis and with the Shi’a—who are harshly discriminated against by the regime—thus potentially leading to internal trouble, especially from a Wahhabi clerical class that believes the Shi’a are a worse enemy to Islam than the Jews. And if the Saudis don’t condemn the attack, it will further the narrative—alarmingly common in the West, and being pushed by the Saudis’ Iranian nemesis—that the Saudi government supports ISIS. Thus, the Saudis have the choice of damaging their relations with their population or damaging relations with their international allies—and opening space for ISIS in either case.

From this it should be obvious that ISIS’ strategic reach and capability to formulate and execute long-term policy is growing, not diminishing, even while under attack from an American-led Coalition.

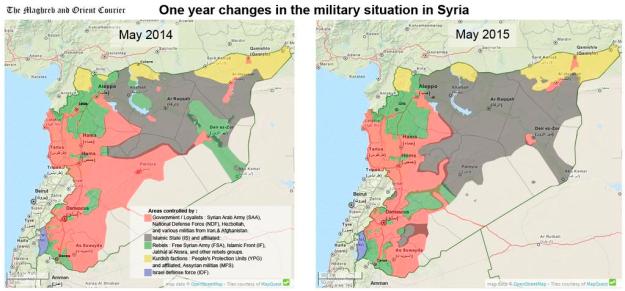

In its heartland, ISIS also clearly has the strategic upper-hand. The U.S. Iraq-first strategy was always a failure given that ISIS’ most important territory is in Syria—its de facto capital in Raqqa and a shelter in the event of territorial losses in Iraq—but now it is also a tactical failure. The fall of Ramadi to ISIS in Iraq’s most important Sunni province, Anbar, on May 17, was a major strategic setback, putting a third provincial capital under ISIS’ control and putting the takfiris on a direct road eighty miles to Baghdad. The fall of Palmyra in Syria on May 20 has opened up the chance for ISIS to complete its conquest of Deir Ezzor and to strike into Homs Province and even Damascus.

While Obama has made plain that Syria is not his problem, even the Iraq component of the anti-ISIS strategy now lies in ruins. Roughly 6,000 Iraqi forces fled in the face of 150 ISIS jihadists, according to Ali Khedery. More importantly, the last remnants of the Sunnis among the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF)—namely the Anbari wings of the Iraqi Special Operations Forces (ISOF) and Ministry of Interior Emergency Response Battalion (ERB)—have fallen apart and been discredited; these forces bet on Baghdad, and Baghdad did not extend the needful help.

It was during the tenure of Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki (2006-14) that the Sahwa/Sons of Iraq, the Sunni militias who had worked with the Americans to destroy ISIS’ predecessor in 2007-08, were allowed to wither and die: starved of funding and their leaders witch-hunted out of the government. This formed a situation, not unlike Syria, where the regime and ISIS worked in tandem to crush the Sunni moderates, exacerbating sectarian tensions and opening a security vacuum that ISIS filled for Sunnis with no other choice against a vengeful, Iran-supported autocracy.

The Shi’a politicos in Baghdad were never pleased with the Sons of Iraq, not least because numbers of tribal leaders were formally aligned with the Ba’ath regime—tribal politics is an unsentimental business and those with power and funds can at least influence their allegiance—and many Shi’ites feared the Sahwa would launch a coup. American forces buffered Shi’a concerns about a coup and Sunni fears about majoritarian repression—until the 2011 pull-out, which gave free-reign to Maliki’s most ruinous temptations and those of his Iranian patrons. The increased persecution of the Sunnis by Maliki’s government led to a protest movement that was violently suppressed and by late 2013 the insurgency was back online.

Given that Baghdad’s and Iran’s sectarianism is what recommenced the Iraqi insurgency, creating a sectarian chaos that made ISIS once again seem like a viable vehicle for Sunni security, it is extraordinary to see it proposed that Hashd al-Shabi, composed overwhelmingly of Iranian proxy militias and led by Hadi al-Ameri, should fill the security vacuum Baghdad/Iran created in the first place.

Leaving aside that sending an Iranian-controlled, sectarian Shi’ite force into al-Anbar that recognizes little difference between ISIS fighters and military-age Sunni males will swell rather than diminish ISIS’ ranks, it simply cannot work. 30,000 Sons of Iraq and 20,000 embedded U.S. forces brought peace to Anbar Province; the Hashd cannot come close to those numbers.

In Tikrit, the Hashd had the emotional issue of Speicher to work with, the sickening massacre of 1,700 Shi’a cadets by ISIS during the June 2014 takeover of Tikrit, which convinced Shi’ites from southern Iraq they had something to fight for in Tikrit, and allowed a force of 30,000 men to be put together. But it was a fiasco: 750 ISIS jihadists (at most) held out against the Hashd, which lost up to 6,000 men, for a month, the Hashd only broke through in the end because of U.S. airstrikes.

Given the predictable horrors inflicted on Tikrit afterward, it makes one seriously doubt the wisdom of being Iran’s air force—a doubt reinforced when U.S.-designated terrorist organization and Iranian proxy Kataib Hizballah is one of the beneficiaries of U.S. airstrikes despite threatening to shoot down U.S. planes because of U.S. support for ISIS! Sending the Hashd into Sunni areas expands ISIS’ ranks with Sunnis looking for protection, and the U.S. airstrikes in support of Iran’s proxies—the bizarre spectacle of supporting Shi’ite terrorists to defeat Sunni terrorists—buttresses the ISIS selling-point of being the Sunnis’ only defender by ratifying the ISIS narrative of an American-Iranian conspiracy against the Sunnis.

Various plans to form a Sunni National Guard to take over local security in al-Anbar have foundered because of the opposition of Iran-aligned Shi’a Islamists in Baghdad. The truth is that “powerful elements of Baghdad’s Shia ruling class fear empowering Iraq’s Sunnis more than they fear allowing ISIS to continue attacking and bleeding the country’s Sunni regions,” as Michael Pregent and Jacob Siegel have written. Iran has control of the strategically important areas of Iraq and Syria that inter alia keep open the lifeline to Hizballah, Iran knows it cannot rule over all of those Sunnis currently under ISIS’ control, and in any case ISIS’ presence serves Iran’s purposes: it keeps Damascus and Baghdad off-balance and reliant on Iran, giving Iran the weak and dependent neighbours it always wanted. This is why there has been such a lack of urgency not just since Ramadi’s fall but in the eighteen months it was under threat during which its fall could have been prevented.

What happens next is difficult to say. ISIS might well take a run at Baghdad: it cannot take the city—Iran has it too well defended—but like Operations BREAKING THE WALLS and SOLDIERS’ HARVEST between the summer of 2012 and the fall of Mosul, a massive coordinated attack by ISIS would help demonstrate the weakness of the government and discredit the State while inciting a Shi’a overreaction that can be used to force Sunnis to look on ISIS as their only protection. ISIS domination of Anbar Province positions them well to approach Deir Ezzor from two directions, should they so choose, and it provides ISIS even more strategic depth to retreat, if they come under pressure in Iraq, to their most strategic territory in Syria which isn’t even under threat in the U.S. strategy. In Syria, the capture of Palmyra gives ISIS a staging ground for raids west and shores-up their hold on the east. Meanwhile, ISIS is advancing at Iraq’s largest oil refinery in Baiji, where Iranian forces are directly leading the anti-ISIS fight. Many sectarian faultlines to be inflamed and many weak and disorganized foes are available for ISIS to expand its Takfiri Caliphate and embed itself in local institutions and populations.

In short, we are where we have been for many months: the only motivated, effective anti-ISIS forces on the ground are the Sunnis—the Kurds, the Syrian rebels, and the tribes on either side of the Iraq-Syria border—and they are in dire need of Western help that keeps being promised and never arrives. The U.S. policy aligning with Iran against ISIS has failed: it is expanding ISIS faster than it is degrading it, and Iran simply isn’t capable of doing what the U.S. wants it to—it doesn’t have the man-power to create anything but chaos. Allowing Iran a veto over U.S. arms-provisions in Iraq is starving the forces—the Kurds and the Sunnis—who can sustainably defeat ISIS in favour of the force that restarted the insurgency that allowed ISIS to move back into Iraq in the first place.

President Obama said in his interview with Jeffrey Goldberg published on Thursday, “I don’t think we’re losing [against ISIS],” which raises the terrifying possibility the President is going to stay the course on a policy that “has failed,” as Hassan Hassan bluntly put it. “The idea that the Islamic State is losing or declining now seems absurd.”

Reblogged this on Utopia – you are standing in it!.

LikeLike

Pingback: Islamic State Spokesman Admits Caliph’s Deputy is Dead, Invites Armageddon | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Adnan al-Suwaydawi: Saddam’s Spy, Islamic State Leader | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Come il Regime Siriano ha Finanziato lo Stato Islamico – Le Voci della Libertà

Pingback: The West Helped the Assad Regime and Its Allies Take Palmyra | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Assad and Russia Losing Palmyra is No Surprise: They Cannot Defeat Jihadism in Syria | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: Crisis and Opportunity for Turkey and America: The Minbij Dispute | The Syrian Intifada

Pingback: The Syrian Regime’s Funding of the Islamic State | Kyle Orton's Blog