By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on April 26, 2016

This essay, written to tie together my work on the relationship between the Saddam Hussein regime and the Islamic State, was completed last summer and submitted to an outlet, where it entered a form of development hell. After giving up on that option late last year, the opportunity arose to get a shorter version published in The New York Times in December. But I procrastinated too long over what to do with the full essay and a recent change in my work situation means I no longer have the bandwidth to go through the process of finding it a new home, so here it is.

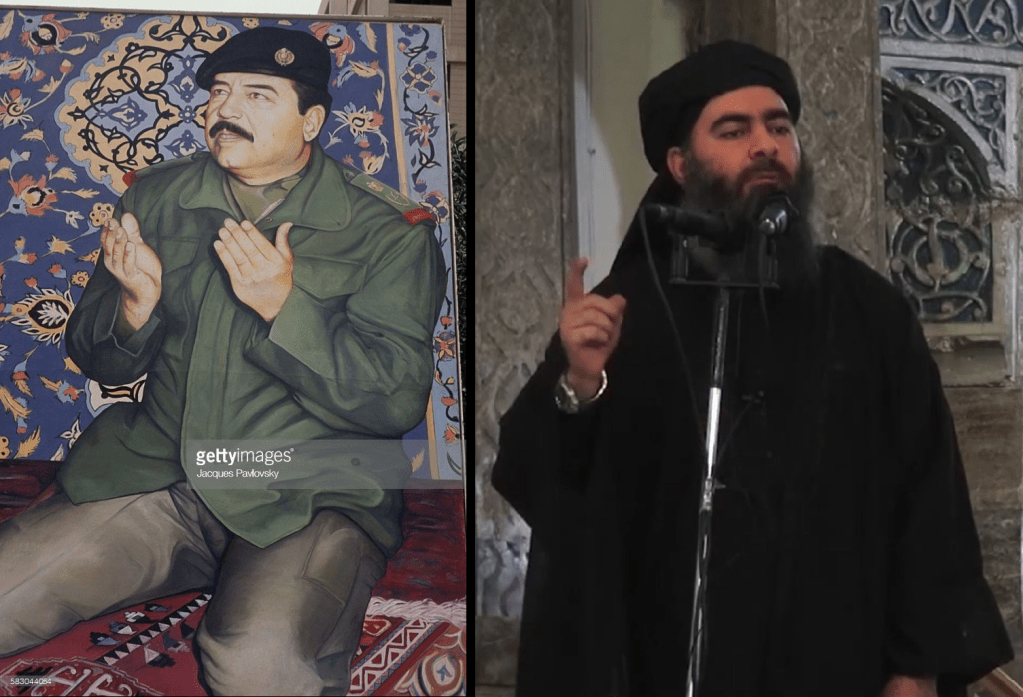

“Abu-Bakr al Baghdadi is a product of the last decade of Saddam’s reign,” argues Amatzia Baram, a scholar of Iraq. He is correct in at least three ways. First, in its last decade in power, the Iraqi Ba’ath regime transformed into an Islamist government, cultivating a more religious, sectarian population on which the Islamic State (ISIS) could draw. Part of Saddam Hussein’s “Faith Campaign” also involved outreach to Islamist terrorists, including al-Qaeda, which meant that the synthesis of Ba’athism and Salafism that fused into the Iraqi insurgency after the fall of Saddam was already well advanced by the time the Anglo-American forces arrived in Baghdad in 2003. Second, the ISIS leadership and military planning and logistics is substantially reliant on the intellectual capital grown in the military and intelligence services of the Saddam regime. And finally, the smuggling networks on which ISIS relies, among the tribes and across the borders of Iraq’s neighbours, for the movement of men and materiel, are directly inherited from the networks erected by the Saddam regime in its closing decade to evade the sanctions. The advantages of being the successor to the Saddam regime make ISIS a more formidable challenge than previous Salafi-jihadist groups, and one that is likely to be with us for some time.

Islamist Outreach and The Faith Campaign

It is often contended that Saddam’s regime was secular. This was true from the time of the Ba’ath Party coup in 1968 until the late 1970s. Saddam initially resisted the “return of Islam”. After brutally repressing Shi’ite riots in southern Iraq in February 1977, Saddam gave a series of programmatic lectures saying that the Ba’ath Party should not try to outbid the religious parties on their own turf because the Ba’athists would lose that contest and the regime would unravel. Saddam instead staked out a case for the Ba’athists being good Muslims but not attempting to rule by Islam. This position was shaken by the Islamic Revolution in Iran in 1978-79. Almost immediately after Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini swept to power in Iran in February 1979, Iraqi Shi’a unrest recommenced, with many awaiting an “Iraqi Khomeini”: Saddam’s crackdown brutally murdered the man, Grand Ayatollah Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr, they had pencilled into the role. It took more than a year for Saddam to pacify Iraq, and in September 1980 Saddam went to war directly with the Iranian Revolution.

On the Sunni side, Saddam’s nemesis was the Muslim Brotherhood, represented in the Iraqi Islamic Party (IIP). After the 1968 Ba’athist coup, the Brothers were severely repressed and went into something like dormancy between 1969 and 1979, according to Joel Rayburn, a former intelligence officer in Iraq and advisor to David Petraeus, in his book Iraq After America. What revived the IIP was rage at Saddam fighting fellow Muslims by invading Iran. The Brethren—like most Islamists, Sunni and Shi’a, were electrified by Khomeini’s triumph over the Shah as a demonstration that an Islamic State was possible—and with permission from the Brotherhood’s general-secretary Umar al-Tilmisani in Cairo, the IIP began to work against the Saddam regime. Notably, the Iraqi Brotherhood did not engage directly in terrorism, though it cooperated with Iranian-orchestrated opposition elements that did, like the Dawa Party, one of the building blocks of the region-wide Khomeinist cadre that became the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and its Lebanon-based unit, Hizballah. What the Iraqi Brotherhood focussed on was things like facilitating the escape of deserters to Kurdistan. The IIP network was discovered, to the great astonishment of the regime, in 1986, and entirely rolled up by the end of 1987. Many hundreds were arrested and sentenced to death, though most sentences were commuted and soon the Brothers were released (see below).

Between 1979 and 1982, there had been a noticeable increase in religiosity in Iraq, even among Ba’ath Party members, Baram writes in a 2011 paper, “From Militant Secularism to Islamism: The Iraqi Ba’th Regime 1968-2003”. The Saddam regime again tried to hold firm. In June 1982, at the Eighth Regional Iraqi Party Congress, al-tadayyun (ultra-religiosity) was harshly condemned. It should be said: Saddam did not have a lot of choice at this time. The initial Iraqi invasion of Iran had stalled in 1981-82, and Saddam was pressing—against Iranian opposition—for a ceasefire; any concession internally in an Islamist direction at that point would have been seen as weakness and could have unravelled the entire regime structure in the south, which largely rested on a class of Shi’a collaborators.

Nearly as soon as the time of peril passed, Saddam turned to the Islamists. Saddam had already extensively supported the Brotherhood’s revolt in Syria in 1979-82 and in April 1983, Saddam held his first “Popular Islamic Conference” (PIC) in Baghdad with nearly 300 religious activists and scholars. Saddam hoped to counter the Iranian propaganda that labelled him an infidel and to frame the conflict with Iran as defensive. Though Saddam had invaded Iran, there was some truth to his claim of defence by this time: Saddam had been willing to settle for a ceasefire since early 1981—i.e., six months into the war—but Khomeini wanted to install a sister republic in Baghdad, and the Imam’s intransigence would drag the conflict out for eight years, double the length of the First World War. The not-so-subtle message of the first PIC was to label Iran the “aggressor” and demand it call off its campaign.

The second PIC in 1985 expressed exasperation that Iran had not heeded the ceasefire call of the first meeting. On July 24, 1986, the Pan-Arab Leadership (PAL), the Ba’ath regime’s highest ideological institution, met to formalize the shift to an alliance with Islamists internationally. The influence of the PICs was expanded in 1987 when Saddam set up the Popular Islamic Conference Organization (PICO) with a permanent headquarters in Baghdad. Ironically, given how instrumental Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf States were in bringing together these pro-Saddam Islamist conferences (most of the Islamist leaders being on the Gulfies’ payrolls), after Saddam annexed Kuwait in August 1990 and the Saudis called in the Americans to prevent Saddam attacking them, the Islamists largely sided with Saddam.

Already in the late 1980s, Saddam was taking internal steps toward Islamization. It was very noticeable that when Ba’ath Party founder Michel Aflaq, a Christian, died in June 1989, Saddam’s media claimed he had converted to Islam. The claim was not inherently implausible since Aflaq had always maintained that Arabism was best expressed through Islam. Whether Aflaq really did convert at the end or not, what matters is the use Saddam made of the claim. Saddam University for Islamic Studies was established in November 1989 with great resources devoted to it. In mid-1990, the Saddam Centre for the Reciting of the Qur’an was established at the Great Mosque of Kufa. This was the beginning of a “massive campaign designed to turn the study of the Qur’an and Hadith into a national intellectual focus,” Baram reports after studying the regime’s documentation. By mid-1992, some 60,000 students were attending Qur’an memorizing courses in mosques.

Baram documents the intensified Islamization of the Saddam regime either side of the U.S.-led Coalition evicting Saddam’s army from Kuwait in January-February 1991. Three days before the Coalition air campaign began in January 1991, the phrase “Allahu Akbar” was added to the Iraqi flag. On the heels of that, Islamic banking was introduced; a massive campaign of mosque-building and madrassa-opening began; zakat, the Islamic poor tax, was imposed; and Saddam made a special show of his personal involvement in rebuilding the holy sites he had ordered destroyed during the unmerciful repression of the Shi’ite uprising that followed the ceasefire in Kuwait. This continued through 1992, with clerics given plots of land and Saddam ordering that the Qur’an be taught right from the first grade. The result, Baram notes, was “newly-recruited teachers [teaching] the six years olds about issues of personal status and about the fires of Hell,” leading to parental complaints and childhood nightmares.

The Faith Campaign (al-Hamla al-Imaniyya) formally began in June 1993. Izzat Ibrahim ad-Douri, Saddam’s long-time deputy, would be the key implementer of the policy. “Saddam chose to mainly promote Salafi Islam … as an alternative to the Muslim Brotherhood, whom Saddam considered a threat to his rule,” Rayburn explains. The intention was to create what Rayburn calls a Ba’athist-Salafist synthesis that would legitimize the regime. Baram notes that the Faith Campaign Islam was, initially, “most likely a cynical step,” and it certainly followed the rise in religiosity rather than led it. But it is noteworthy that Saddam persevered with the Faith Campaign—as he had the outreach to the Islamists—against significant opposition within senior ranks of the party, particularly from Tariq Aziz, a Christian and part of the “Quartet” that dominated Ba’athist Iraq, and Barzan Ibrahim, Saddam’s half-brother and the head of the Iraqi Intelligence Service (IIS).

The changes were as remarkable as they were rapid. Frequent visits to the mosque no longer marked people down for extra attention from the secret police. Most night-clubs in Baghdad were closed. Public consumption of alcohol was banned and only non-Muslims were permitted to sell liquor. Gambling was outlawed. Qur’ans were mass-distributed. Religious exams were imposed on the Ba’ath Party, and Party meetings—where whisky had previously been served—were stopped for prayers. Elements of the shari’a began superseding the secular law. Hudud punishments like cutting the hands off thieves became common, and these punishments began to be shown on State TV. Prostitutes and homosexuals were executed. Perhaps most consequentially, in October 1993, Saddam ordered that religious teachers be given a monthly pay-rise of 100-150 dinars, making Qur’an teachers the best-paid in the country, vastly increasing their numbers, and redeeming the job from its status of cultural inferiority. This was part of a pattern of making religious leaders the centre of communities, a dynamic that had a momentum of its own as Iraqis sought religious solace under the misery of the Saddam-plus-sanctions regime—and in the aftermath of the regime these leaders and their mosques would serve as nerve-centres for the insurgency, with the imams as message-carriers and houses of worship as weapons stores.

For those who argue that the Ba’athist leaders did not really believe in what was propagated by the Faith Campaign, the only possible response is: so what? An Islamist government was formed in Iraq that imposed what Baram calls “shari’a-lite”. What difference does it make if the leaders really believed it when the Holy Law was being imposed, when a religious revival and religious leaders were empowered, and the regime worked through all manner of Islamists—including al-Qaeda and the Taliban—in its foreign policy? As it happens, the evidence does suggest that Saddam became a believer before the end. The personal sacrifice of fifty pints of blood to write a Qur’an, the mosque-building, sponsorship of imams, implementation of the shari’a, and other Islamization measures were atonement that Saddam hoped would have him forgiven in the eyes of God.

Nor was Saddam the only Ba’athist who turned to God for forgiveness. Saddam dispatched military and intelligence officers to mosques, both for religious instruction and to infiltrate the mosques to bring them under control. The former worked somewhat better than the latter. Men involved in the regime’s crimes found comfort in the Islamic teaching of yetoob, the idea of confessing one’s crimes to God and receiving absolution for them, Rayburn writes, adding: “Most of the officers who were sent to the mosques were not deeply committed to Baathism by that point, and as they encountered Salafi teachings many became more loyal to Salafism than to Saddam.”

Some of these “pure” Salafis would launch attacks against the regime, and it is the evidence in the regime archives of the repression of these independent Salafis that is often used as evidence that Saddam remained hostile to Islamism down to the end. What the evidence actually shows is that the regime remained totalitarian, at least in intent (its capacity began to wane in the late 1990s). The regime crushed all opposition, including anti-Saddam Salafists, who were often labelled “Wahhabists” to associate them with Saudi Arabia and treason, as well as ideological deviance. This had no impact, even theoretical, on a Faith Campaign designed to create a religious current under Saddam’s leadership, and in practice the “pure” Salafi Trend was not targeted as a whole—or really at all per se. On the contrary, despite repeated entreaties from Barzan Ibrahim and others to do something to curb the “pure” Salafis before they took over the regime, Saddam refused. The long-standing “pure” Salafi Trend was empowered alongside the Ba’athist-Salafists—as was the Muslim Brotherhood, come to that, with the Iraqi Ikhwan Muhammad Ahmad al-Rashid being allowed to become a prominent source of inspiration.

The Inflammation of Sectarianism Under Saddam

While the regime disliked, and acted forcefully against, any independent Islamist trend developing, there was a sectarian dimension. Despite the Ba’athist presentation of a sect-blind Arab nationalism, hundreds of years of Sunni ascendancy in Iraq continued under the one-party State formed after 1968 and it created tensions with Iraq’s Shi’ites that had become a rupture by the time the Faith Campaign began.

The Saddamist inner circle was largely drawn from a handful of Sunni tribes and even in their most secular phase they were wedded to a pan-Arabism that was Sunni hegemony by another name. The Tikriti tribesmen were astonishingly ignorant of Shi’ism—the regime leaders only discovered in May 1979 that there were both pro- and anti-Khomeini currents in Shi’ism—but this nuance did little to ameliorate their broader sense that Shi’ites were a “fifth column” after the Khomeini-inspired domestic disturbances of the 1970s.

This was the backdrop to the Saddam regime propaganda during the Iran-Iraq War, which was significantly nationalist and racist—the pamphlet produced by Saddam’s uncle, Three Whom God Should Not Have Created: Persians, Jews, and Flies, is a notorious example—yet it had also been anti-Shi’a. And it was not just propaganda. Tens of thousands of Iraqi Arab Shi’ites, especially if they had (or were accused of having) Persian ancestry, and Fayli Kurds (a mostly Shi’a tribe) were deported to Iran during the war. In Saddam’s mind, his actions were retrospectively justified as pre-emption by the fact that some Shi’ites did answer the Iranian Revolution’s call and cross over to the other side, forming the Badr Corps, an extension of the IRGC which fought alongside Iranian troops during the war, waged a shadow war against Saddam throughout the 1990s, and then became the seedbed for the Shi’a militias or “Special Groups” that terrorised Sunnis and killed hundreds of Coalition soldiers after 2003.

Tense as State-Shi’a relations had become, the turning point was March 1991, when, in the wake of Saddam’s expulsion from Kuwait, a broad Shi’a rebellion erupted in southern Iraq. Iran took a relatively hands-off approach to the Shaaban Intifada—Tehran was nervous about the American reaction if it went all-in—but the Badr Corps did get involved, and its presence helped poison the atmosphere and rally Sunnis, Christians, and middle-class Shi’ites in Baghdad around the regime. The terrible massacres used to suppress that uprising left scars that never healed. It confirmed all the worst suspicions of both sides. For Saddam, the Shi’ites were now indisputably a fifth column. For the Shi’ites, Saddam’s State was hostile beyond redemption.

As Baram explains, the Shi’a areas throughout the 1990s were treated virtually as occupied territory, with the population openly regarded as untrustworthy, needing to be surveilled by large numbers of troops and militias. A key instrument for the regime here was the Fedayeen Saddam (Saddam’s Men of Sacrifice), a paramilitary formation created in October 1994, initially under the command of Saddam’s eldest son, Uday, and later his younger son Qusay. The Fedayeen Saddam became one of the most enduring elements of the Saddamist-Salafist fusion. The Fedayeen’s main task was internal control, ensuring there was no repeat of the 1991 intifadas. Over time, enforcing internal order meant enforcing Islamic law—inter alia beheading prostitutes and the men who hired them in front of their homes in the presence of a conscripted crowd—making the Fedayeen Saddam into something like a mutaween (religious police). This was not the only premonition the Fedayeen gave of ISIS. The Fedayeen had at least planned terrorism abroad during the later Saddam years and ran camps that trained up to 8,000 foreign Islamic terrorists, producing gruesome propaganda videos to demonstrate their power. During the 2003 invasion, the Fedayeen Saddam “proved themselves as the most audacious and fanatic fighters on the Iraqi side,” Baram notes, fighting on in Baghdad with thousands of foreign Arab Salafist volunteers long after the Republican Guard had called it quits, and then “many … fled to Syria, where they constituted the nucleus for the establishment of ISIS”.

The deployment of the Fedayeen Saddam in the south obviously antagonised Iraqi Shi’ites. Meanwhile, the regime, more paranoid than ever, fell back even further on trusted familial relations, gradually excluding everyone else. An already clan-based regime hardened into a sectarian one and a special effort was made to purge Shi’ites from positions of authority in the Ba’ath Party State, both regionally and at the centre. The lack of reconstruction in the south, which had been devastated by the American bombing during Operation DESERT STORM and the behaviour of Saddam’s forces as they suppressed the 1991 uprising, was not primarily conceived of as an issue of sectarian vengeance, even if it took on such colourings on all sides. On the one hand, not rebuilding increased the alienation of the Shi’a from the State, as the regime knew and would have ideally liked to avoid. On the other hand, pouring money into the Shi’a areas would reduce their dependence on Baghdad for basics like trucking water in, and risk empowering local leaders who could once again incite a challenge to the regime.

These same considerations induced a schizophrenic approach to Shi’a religious festivals: Saddam’s regime knew that banning them created further bad blood, but the regime feared that granting space to Shi’a festivities would create occasions for anti-regime demonstrations—and the few times experiments were made with more leniency toward the Shi’a, this is exactly what happened. That there was never any ban on Sunni public religious events—and never any felt need for a ban from the regime—reinforced everyone’s prejudices.

When the Faith Campaign was proclaimed, it was conceived as ecumenical; in execution, it was self-evidently pro-Sunni. The Faith Campaign was possibly the best-funded patronage system in Iraq from 1993 onwards, but the issue of rebuilding the south had not been resolved. The upshot was that far more money went to Sunni mosques than Shi’a husayniyyas and shrines. Nor had the regime managed to find a workable formula for public expressions of Shi’ism. The result was that, while imams in both Sunni and Shi’a areas were empowered, the strictures were much tighter for Shi’ites. Dissenting Shi’a clerics were treated far more harshly for far lesser offences than their Sunni counterparts. Indeed, any Shi’a cleric who became a potential to be a threat—by, for example, becoming too popular—was, in the fashion of the KGB that trained Saddam’s military-intelligence apparatus, pre-emptively liquidated. Such was the case with Grand Ayatollahs Mirza Ali Gharavi, Murtada al-Burujirdi, and Mohammed Sadiq al-Sadr, Ayatollah Hussain Bahr al-Uloom, and Shaykhs Hussain Suwaidawi and Ali al-Fraijawi. Actual dissent from Sunni clerics tended to lead to them being roughed up and receiving short prison sentences, rather than being killed. Iraqi Shi’ites felt they were living under a system of wilful Sunni supremacy, and sectarianism guarantees a counter-reaction: what little space Shi’ites had, culturally and religiously, was used to recalibrate their own identity in terms that had a distinct anti-Sunni edge—alarming the regime and its Sunni retainers even further.

“In the end, Saddam’s Faith Campaign helped transform Iraq by giving it an extra push in the direction of an authentic Islamization process that had already been set in motion,” Baram writes. “[T]he mosque eventually became more influential than either the party headquarters or the tribal mudif. … When the U.S. invaded Iraq they found a more religious and more sectarian society than had ever been the case since the 1950s.”

The Post-Saddam Insurgency

There is no doubt that the former regime elements (FREs) coordinated the early formation of the insurgency in 2003 and that they did so based on structures and a program set in train by the old regime. The FREs provided a core around which the insurgency was built, a vanguard of specialists that could distribute weapons, money, and expertise through innumerable other armed groups. The insurgency was not hierarchical, but the fallen regime’s leaders were able to exert influence by directing the flow of resources from exile in Syria. Because of the common interests, and the connections the Saddam regime had already made to them, foreign-led Salafi-jihadists linked to al-Qaeda attached to this core of FREs and acted as shock troops.

Over three decades, Saddam’s patronage—of military-intelligence personnel, tribes, religious leaders, and organized criminals—created a sub-State structure invested in the regime, if not exactly the dictator. The Faith Campaign had added separate networks of Iraqi Salafists, and the success of the Campaign could be registered in the number of them who had come into the fold, as State employees of various kinds. Even those Iraqi Salafists who had remained effectively opposed to the regime, so long as their defiance was not public, had benefited from its lax policy towards Islamists, and its decreasing capability. The “pure” Salafists had bided their time, taking advantage of Saddam’s crumbling regime, and now their moment had arrived.

Iraqis returning to post-Saddam Iraq, after two and three decades in exile, were flabbergasted by what they found. The old compact of a Sunni political elite and a Shi’a merchant class had been shattered. State patronage had gone overwhelmingly to Sunni Arabs and the Shi’ite estrangement from the State, and the Sunnis more broadly, was as striking as it was shocking. It had always been a myth that there was a significant amount of inter-confessional marriages in Iraq, but the potency of the myth that many of these urban middle class Iraqis had taken into exile with them bespoke the elite orientation of Iraq before the 1980s—secular and “modern”. In 2003, the veil was everywhere, people took their cues from imams, and from top to bottom of the society, identity was overwhelmingly constructed along the lines of sect, with deep grievances one against the other.

The whole spectrum of Sunni society was united in a belief that Iraq was theirs, and they would not let their dominion go willingly. The Coalition found this Sunni revanchism to be the centre of the resistance to the new order. In addition to resenting their loss of power and prestige, and for some an ideological opposition to Shi’ites’ right to rule, the heavily-armed Sunni minority feared a generalized retribution from the Shi’ites. The takeover of the Interior Ministry, thus much of the police by the IRGC/Badr Corp, legitimized these fears. Badr targeted members—even low-ranking ones—of the old regime, and ran secret prisons where random Sunnis were kept in abysmal conditions and tortured (at best). That this happened under the nose of the Coalition ratified the propaganda, started by Saddam himself and taken up by the jihadists, of an American-“Safavid” conspiracy against the Sunnis. “There was no secular Sunni resistance at all”, as Rayburn notes, but whether a Sunni insurgent group wanted the restoration of Saddam’s Islamist regime or a “purer” Islamic State was a question they could leave to another day. Harbouring existential fears, the FREs, tribes, Iraqi Sunni Islamists, and foreign jihadists could put aside their ultimate goals and unite around the short-term common-interest in instability and ejecting the Americans

When Saddam was overthrown in April 2003, there were up to 95,000 FREs still under arms, including: 26,000 Republican Guards, 30,000 Fedayeen Saddam, and 31,000 officers, agents, and analysts of the IIS. There were also dedicated formations of Ba’athist militiamen such as those formed by PROJECT 111 in late 2002, which trained a special cadre of 1,000 intelligence officials in sabotage and covert operations. Saddam had issued an “Emergency Plan” or “doomsday directive” in January 2003, which notably did not predict a full-scale Anglo-American invasion of Iraq but instead envisioned a limited attack sparking an internal rebellion, into which Iran would intrude. To the last, Saddam was so deluded he believed the main threat to his regime came from Iran, not America. Saddam thus concentrated on beefing-up the Fedayeen Saddam and other paramilitary forces deployed in the Shi’a south after 1991 to prevent another Shi’a revolt. This military infrastructure in the south was fed by the essentially criminal syndicates Izzat al-Douri had set up to evade the sanctions by smuggling across Iraq’s borders—a source of revenue that in turn provided the resources for the internal patrimonial networks, the Faith Campaign primary among them, which gave the regime some pillars of support. The “doomsday directive” had placed the regular army along the border and given instructions for how the regime’s men should fight their way back to power should communication with central command in Baghdad be lost. Unintentionally Saddam had laid the ground work for an insurgency.

The “doomsday directive” gave specific instructions to reconnect as a decentralized, lateral network, which could not be decapitated; for the regime’s records to be destroyed, preventing any new administration finding the agents of the old order still embedded in the bureaucracy; and for the regime’s loyalists to use weapons bought on the black market to attack infrastructure and pre-emptively assassinate possible leaders of a new government to prevent it stabilizing. Predicting better than the West, the Saddamists thought that the hawza in Najaf and exiled clerics like Mohammad Baqir al-Hakim would emerge as major figures of a post-Saddam Iraq. It is highly instructive that when Hakim was struck down in a massive truck bombing in August 2003, the explosives had clearly come from regime stocks and the man who planted the charges was Sami Muhammad Ali Said al-Jaaf (Abu Umar al-Kurdi), a close associate of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the founder of ISIS in 1999. Here, at the outset of the insurgency, was intimate collaboration between the Saddamists and what became ISIS, which had been on Iraqi territory when Saddam was still in power.

The lead coordinators of the insurgency were Izzat al-Douri and Mohammed Younis al-Ahmed, based in Syria. With the cash and weapons looted from the fallen regime, these men were able to provide the resources and thus exert influence over the insurgents. Douri/Younis concentrated patronage on the Ba’athist-Salafist groups dominated by FREs and the tribes who were outraged by the Coalition bringing to an end the smuggling operations they had been put in charge of. In addition to the Ba’athist-Salafists, the “pure” Salafists, and the tribes, the local insurgency included the Muslim Brotherhood, Saddam’s archenemy, who now found patronage from Douri. Harith al-Dari, a Brotherhood leader from al-Anbar, was harassed out of Iraq in the early 1990s. Al-Dari, however, maintained relations with Iraqi intelligence, and when al-Dari returned to Iraq after the fall of the regime, he became director of the Association of Muslim Scholars (AMS) and “spiritual leader” of the insurgency, and there is no doubt he did so with the support of FREs, both the intelligence services and the Fedayeen Saddam and Ba’ath militias. Al-Dari set up shop in the Mother of All Battles Mosque and renamed it Umm al-Qura (Mother of All Cities, the phrase in the Qur’an Muslims believe refers to Mecca). The mosque and the historic Abu Hanifa complex became open citadels of the insurgency. These groups were fighting mostly for the restoration of the old order.

Douri, however, made no effort to keep supplies out of the hands of foreign-led Salafi-jihadists whose agenda was holy war against the Americans and the Shi’ite heretics. Rather to the contrary: Douri thought they could be used to get back to power and then sidelined. Douri’s assistance to the Salafi-jihadists who attached to the core of FREs that formed the early insurgency included putting his autoshops, which worked on stolen cars from Europe brought into Iraq through Jordan, at the service of Islamist suicide bombers brought in from the Arabian Peninsula, Syria, and Muslim Africa via connections made by the Faith Campaign, underlining that the Ba’ath-Qaeda alliance did not start after 2003. Saddam’s enlisting of Islamists in his foreign policy had included al-Qaeda since 1992. Saddam formed an effective non-aggression pact with Osama bin Laden in 1993, and supported various al-Qaeda affiliates, notably in Algeria and the Philippines. Manila expelled Saddam’s diplomats in February 2003 for involvement in an al-Qaeda bombing that killed U.S. Marine Sgt. Mark Wayne Jackson. More important than these various contacts outside Iraq was the Saddam-Qaeda collaboration inside Iraq, crystalized in Ansar al-Islam.

In 1998-99, Salafi-jihadists began filtering into northern Iraq via Iran from Afghanistan, many of them Kurds originally from the area. Zarqawi, ISIS’s founder, had been given al-Qaeda seed money for his terrorist group in Taliban Afghanistan, but he had refused to give bay’a (an oath of allegiance) to bin Laden. Bin Laden and Zarqawi had deep differences over tactics and their alliance was based on “rolodex pragmatism,” namely Zarqawi’s excellent Levantine connections. The forming of a jihadi base in northern Iraq was a joint Zarqawi-Qaeda project: bin Laden largely paid for it and Zarqawi loyalists organized it. By late 2001, Ansar was formed from a merger of disparate groups and controlled a significant strip of territory. Saddam supplied weapons and money to Ansar to attack the Kurds, and Ansar’s decision-maker was Saadan Mahmoud Abdul Latif al-Aani (Abu Wael), an officer of Saddam’s mukhabarat who had for years been an outreach coordinator to Islamists.

Ansar also highlights “the agendas of regimes in Iran and Syria, … without which we cannot truly understand ISIS today,” as Michael Weiss and Hassan Hassan write in their book, ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror. Zarqawi relocated to Iraq in April 2002 and to Baghdad in May 2002, but then went on a tour of the Levant, gathering bay’a from a group of holy warriors in Syria that included ISIS’s current spokesman Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, making links with the militants at the Ain al-Hilweh Palestinian “refugee camp” in then-Syrian-occupied Lebanon, and organizing the assassination of USAID worker Laurence Foley in Jordan in collusion with Bashar al-Assad’s intelligence service. When Zarqawi returned to Iraq, he had erected the “ratlines” overseen by Assad’s mukhabarat that would bring nearly all of the Islamic terrorists into post-Saddam Iraq. (Assad would be found liable in U.S. Federal court for the 2004 beheading of two Americans, Eugene Armstrong and Jack Hensley, by Zarqawi’s gang. The Syrian-to-Iraq flow of muhajireen was so heavy that ISIS predecessor appointed a “border emir,” and this was only slowed after the U.S. struck into eastern Syria in October 2008 to take out a key terrorist facilitator, Abu Ghadiya, who was in a Syrian mukhabarat safe-house.) In November 2002, Zarqawi moved to Kurdistan to take direct charge of Ansar.

During the invasion in March 2003, Ansar—numbering about three-hundred men—fled to Iran, where it was sheltered by the clerical regime. There is even a report that Zarqawi was trained at an IRGC camp in Mehran. Later, Iranian agents were found in possession of “phone numbers affiliated with Sunni bad guys”. Iran’s Badr-derived Iraqi proxies cooperated with the Sunni jihadists against American forces, and an al-Qaeda facilitation network was set up in Iran that operates to this day, now supporting al-Qaeda in Syria. The least that can be said is that Iran never stood in ISIS’s way.

By the early summer of 2003, Douri and the regime remnants were “help[ing] smuggle“ the Ansar fighters from Iran “to central Iraq so they [could] join the fight against U.S. forces.” Ansar—by then melded into Zarqawi’s expanding Jamaat al-Tawhid wal-Jihad (which became al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia (AQM) when Zarqawi finally gave bay’a to bin Laden in October 2004)—was involved in the first three major attacks of the Iraqi insurgency in August 2003.

The awkward fact is that Douri, a Sufi, was regarded as a heretical pagan by both the Ba’athist-Salafists he’d incubated and the “pure” Salafists. Perhaps as a hedge, and not least to his own enrichment, Douri had “fostered a fraternity of Sufi military and intelligence officers inside the Baathist regime,” says Rayburn, “a parallel network to the Baathist Salafis the regime had created.” This Freemason-style secret society was based on the Naqshbandi Order. Between 2003 and 2006, this network operated in the shadows. It would be formally activated as Jaysh Rijal al-Tariqa al-Naqshabandiya (JRTN) after the execution of Saddam Hussein in December 2006 when Douri claimed the leadership of the Ba’ath Party.

The crucial thing about JRTN is that it is deeply integrated into Sunni communities and has agents all through the Iraqi bureaucracy and security forces. From Sunnis in the Tigris River Valley, JRTN could extract “taxes”. In combination with the stocks of cash from the old regime, agriculture, the black market, and donors (many of them ex-Republican Guards) in Jordan, Douri had sufficient standing to not only ride-out the U.S. Surge but an attempted coup by the Assad regime, which wanted to replace Douri with Younis, who had become loyal to Damascus. JRTN’s interest was in ensuring the new order in Iraq did not stick and its main means of doing that was—and remains—informants. JRTN are the termites who by coercion and penetration spread insecurity, shaping the environment for the insurgency. And JRTN can use its information to sub-contract bombings and assassinations via other insurgents when necessary, often without them knowing who they’re working for.

After the formal American occupation ended in June 2004, with the commensurate diminution of the U.S.’s ability to select the Iraqi government, the Sunni Arab leaders who emerged nearly all did politics by day and terrorism by night. This was true of Adnan al-Dulaimi, Khalaf al-Ulayan, and Mahmoud al-Mashhadani. The only major Sunni Arab political leader who did not buttress his political activity with terrorism was Tareq al-Hashemi. What this underlines is that the insurgency was an essentially community-wide resistance movement among the Sunni Arabs: they resented the loss of their primacy and by this time they were beginning to feel the effects of Iran-controlled forces who were persecuting Sunnis.

As in the insurgency, the Saddam regime’s fingerprints were all over the “official” Sunni leaders. Al-Dulaimi was a Brotherhood member arrested in 1986-7 and released in 1991 on the eve of the Gulf War in an amnesty that pardoned Islamists, but not people like Kurdish leader Jalal Talabani. (There are echoes here of Assad releasing the violent Salafists as the uprising began in Syria in 2011.) The Iraqi Ba’ath regime had ostensibly legalized opposition parties in 1988; sensing a “let a hundred flowers bloom”-style trap, al-Dulaimi set about recreating the Brotherhood in secret. Harried by Iraqi intelligence, al-Dulaimi fled to Jordan in 1992, but returned after 2003, like al-Dari, with help from the FREs. Al-Dulaimi was the head of the Sunni Endowment when he organized the assassination attempt against the independent Sunni politician Mithal al-Alusi in February 2005 and al-Dulaimi’s son was arrested in 2007 for involvement in the assassination of an Awakening leader.

Al-Ulayan, an Anbari tribesman and former senior officer in Saddam’s army, was converted by the Faith Campaign and became a key leader of the “pure” Salafists, running Tawafuq, a Sunni Islamist party in the Iraqi Parliament. Al-Mashhadani had been a long-time “pure” Salafi opponent of Saddam’s who was nonetheless tolerated. Al-Mashhadani was al-Ulayan’s most important “pure” Salafi comrade, and the two collaborated in April 2007 in a plot to blow up the Iraqi parliament that killed eight people, despite al-Mashhadani being the most senior Sunni Arab in the government—the Speaker of that very Parliament.

By 2005, ISIS’s predecessor was so powerful it had begun to launch attacks outside Iraq, first in Jordan, then in Lebanon, with a string of bombings in Saida and Beirut in early 2006, claimed in the name of “al-Qaeda fi Bilad a-Sham”. The Assad regime had tried to divert some of the returning AQM/ISIS jihadists it had sent to Iraq to Lebanon. A jihadi faction in Zarqawi’s network, Fatah al-Islam, which certainly has some connection with the Syrian mukhabarat, started a small war in May 2007 at the Nahr al-Bared Palestinian “camp” in Tripoli, something it could not have done if Assad had not released its leaders and paid for it. But jihad came to Syria directly in May 2007 with the announcement of “al-Jamaat at-Tawhid wal-Jihad fi Bilad a-Sham” (The Monotheism and Jihad Group in the Levant). A series of bombings and small arms attacks had preceded this and would follow. What role Assad played in these attacks, which tended to target foreign installations like the American Embassy, is uncertain.

The domination of the insurgency by locals who were part-in and part-out of the government came under challenge in 2005 when the foreign-led networks started to overwhelm the Iraqi insurgency. The perception that AQM/ISIS was a foreign intrusion and its excesses against Sunnis were causing anti-AQM/ISIS resistance among Sunnis by the spring and summer of 2005.

The Surge

Dissatisfaction with AQM/ISIS had been seen in Iraq among the local insurgents as early as May 2005 in al-Qaim, the Iraqi border town through which many of the foreign Salafi-jihadists came from Syria, and further east in al-Anbar around Ramadi through the summer, with clashes spreading into Mosul in late 2005. But these uprisings were defeated by AQM/ISIS because U.S. forces had no mission to support them. In September 2006, the Anbar Salvation Council was founded and the Sahwa (Awakening), the Sunni Arab anti-AQM/ISIS movement, had begun. It still needed to Surge to succeed, however, and in January 2007, President Bush gave the order. 20,000 additional troops were sent to Iraq with an altered mission, a population-centric counter-insurgency strategy. No longer would the Americans stay on bases in the belief that their presence provoked a backlash; now U.S. troops would work closely with the Iraqis to provide security against the insurgents, recognizing that by providing security for the population it would lead to greater assistance in defeating the forces of disorder.

The foreign-led AQM had tried to head-off the Sunni reaction against it by forming al-Majlis Shura al-Mujahideen (The Mujahideen Shura Council or MSC) in January 2006, which included inter alia Jaysh al-Taifa al-Mansoura (The Army of the Victorious Party), an Iraqi Salafist group that emerged after the invasion from elements of the old regime and the anti-regime Salafist networks. This was the beginning of an Iraqization process at AQM/ISIS’s senior levels. In October 2006, MSC became the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI). Zarqawi had been killed in June 2006, and his Egyptian successor, Abu Hamza al-Muhajir, dissolved AQM in November 2006 and became deputy to ISI’s leader, an Iraqi named Abu Omar al-Baghdadi. But the moves by the Islamic State movement to regain their footing were too late.

It should be noted here: this was to be the beginning of eight years of confusion about the relationship between Al-Qaeda and the ISI, creating a problem in the very lexicography used about the Zarqawists in this period. The U.S. military and most Western reporting assumed ISI remained a branch of Al-Qaeda, and this was basically correct, though the U.S. belief that Abu Hamza was really in control—and that Abu Omar might not even exist—was wildly mistaken. To put it simply, the ISI publicly broke ties with Al-Qaeda in 2006 to reduce tensions with the Iraqi jihadists and assist the ISI’s integration with (and ultimate capture of) the insurgency, while in secret ISI remained loyal to Al-Qaeda’s leaders, but ISI was troublesome even while bin Laden was alive and in the absence of his charismatic authority the relationship broke down, leading to ISIS’s expulsion from Al-Qaeda in February 2014.

In April 2007, ISI killed thirty members of the Islamic Army of Iraq (IAI), the largest Ba’athist-Salafist insurgent group. IAI released a public statement of condemnation that included a demand that Osama bin Laden get ISI under control; a ceasefire patched things up for a time but the breach between the local insurgents and ISI could not be repaired. A series of bombings between March and July 2007, of the famed book market on Mutanabbi Street and football crowds celebrating Iraq’s victory in the Asia Cup, helped ignite a wave of nationalistic denunciations of ISI. By the summer of 2007, IAI had called in the Americans to fight off ISI. Even Douri announced in August 2007 that he had “sever[ed] ties with al-Qaeda”, meaning ISI. By the end of 2007, the decision before the Iraqi Sunni insurgents was whether to continue resistance to the New Iraq on a Salafi-nationalist basis, or to join the Sahwa and make an accommodation with the Shi’a-led government.

The Sahwa-plus-Surge continued to degrade and discredit AQM/ISI throughout 2008, and by early 2009 Iraqi politics had passed them by. ISI had declared its “State”, and implied a “Caliphate”, in October 2006, but by this time even Abu Hamza al-Muhajir’s own wife was given to lament: “Where is the Islamic State of Iraq that you’re talking about? We’re living in the desert!” The Surge had opened a space for politics to become the arbiter of disputes, and the schism between locals and foreign-led forces that the Surge exacerbated essentially achieved a sorting out among the Sunni rejectionists, who now fell into two camps: JRTN and ISI.

Many Iraqi rejectionists gathered under JRTN’s banner, which was the only viable Islamist-nationalist option, embedded as it was in Iraq’s communities and the structures of the new government. This is why JRTN was “the only Iraqi insurgent group to have grown stronger during and since the U.S.-led ‘surge’,” according to Michael Knights, an Iraq analyst who has done much work on JRTN. But the cooperation between JRTN and the Zarqawists was not finished; the “blurring” of JRTN continued. Douri was more a manager than a military leader and JRTN remained focussed on corroding the government and being a seedbed of instability. JRTN was partially reinvented by adding a dose of nationalism to its Islamism, but JRTN subcontracted mass-casualty attacks to ISI against defiant tribes and personnel. As ISI tried to recover from the Surge, JRTN’s help would be invaluable.

The Islamic State’s Revival

What the U.S.-led Coalition did not grasp, Craig Whiteside, a Professor at the Naval War College who has worked extensively with ISIS’s internal documents, persuasively argues, is that the Surge was not a done-deal: Islamic State movement responded to the U.S. change in strategy with a change of its own, directed at the U.S.-aligned Sunni tribal leaders who had expelled it from the urban areas of its heartland. Between 2007 and 2010, ISIS waged a very deliberate campaign of assassination against the Sahwa leaders, as documented by Whiteside. JRTN was crucial to ISIS’s success with its shaping operations, providing a favourable environment for ISIS by keeping pressure on the Iraqi government when ISIS was on its knees. JRTN prevented the State imposing its writ on Mosul and its environs, and continued coordination with ISIS, particularly intelligence and logistics to aid this campaign of assassination.

President Obama had withdrawn American troops from Iraqi cities in August 2010 before he pulled all American troops out of the country in December 2011. This opened a security vacuum, but this was the accentuation of a policy begun in 2009, when Obama diplomatically abandoned Iraq nearly as soon as he entered office. The focus of the U.S. on winding down its presence led to a lack of focus on consolidating the gains of the Surge—or indeed understanding (or caring) about how fragile they were. In this category of insouciance is the closing in September 2009 of Camp Bucca, the largest American detention facility for insurgents, and the handing over of the 15,000 or so inmates to Iraqi control.

Most Bucca inmates were released by Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki since they had “only” attacked Americans. (Iranian-run Shi’a militants were also released during this time.) Of the final 7,000 Bucca detainees, only 1,360 were transferred to the Iraqi criminal justice system—these being mostly senior ISIS leaders. Bucca had been notoriously badly run, being little more than a social-networking opportunity for ISIS. The proselytization aspect of Bucca can be overstated: entrants to Bucca could choose which part of the camp they went to—i.e., Salafists self-selected being imprisoned with other Salafists—but the divisions were doubtless porous, and the evidence is quite plain that ISIS members got themselves intentionally arrested to keep safe and make connections. No reform took place in Bucca. But at least these men were contained. Their release allowed ISIS to “have their own surge in 2011,” says Whiteside.

A second American decision—not to intervene early in Syria after the uprising began in March 2011—would allow ISIS further space to mount its comeback. ISIS had dispatched agents into Syria in the summer of 2011, who would form Jabhat al-Nusra. Throughout 2011 and 2012, Nusra worked in Syria to spread the influence of ISIS, by now headed by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, through dawa (missionary) offices, infiltration of Syrian rebel groups, and marrying into prominent Syrian families and tribes. But the reason Nusra took hold so quickly, especially in eastern Syria which became Nusra’s base, is that it was already there: this is where the ratlines sending suicide bombers into Iraq were based, run by the combined efforts of Assef Shawkat, Assad’s brother-in-law and then-head of Military Intelligence who was killed in a mysterious bombing in Damascus in July 2012, and the Islamic State, represented at one stage by Abu Bakr himself. The “flipping” of the networks was easy. Nusra broke with ISIS when Abu Bakr announced, in April 2013, that Nusra had always been “merely an extension” of ISIS, and tried to claim public command of Nusra. Nusra’s leader, Abu Muhammad al-Jolani, a member of ISIS’s predecessor since 2002, rejected this and asserted his independence from ISIS, swearing allegiance to al-Qaeda. Al-Qaeda formally disowned ISIS in February 2014, and open warfare has continued ever since. Many foreign Salafi-jihadists joined ISIS, leaving Nusra as a much more Syrian enterprise, and the Iraqization of ISIS’s leadership had been completed.

In the meanwhile, ISIS focussed on getting its hardened leaders out of jail—an easier task than winning new converts and training them. With help from the resources it was gaining from Syria, ISIS launched several operations—BREAKING THE WALLS and SOLDIERS’ HARVEST—that ran from the summer of 2012 to the summer of 2014, which not only sprung the jihadists’ most skilled technicians but were designed to prove that the State didn’t work and provoke an indiscriminate Shi’a overreaction against Sunnis, allowing ISIS to position itself as the Sunni vanguard. ISIS succeeded on all fronts.

As instability spilled over from Syria and sectarian identities were polarized by that war, Maliki was launching a crackdown. Maliki was not solely being paranoid and sectarian: his government had been under constant attack since 2009. But Maliki was using a building crisis to indulge his most ruinous temptations, and make a manageable problem insoluble. Maliki was completing the Shi’ization of the Iraqi security forces and moving even closer to dependence on Iran. Without U.S. oversight, Maliki reneged on his promise to support the Sahwa, and even targeted their leadership for arrest and worse, while witch-hunting the Sunnis out of the government. Without finance and the weapons to defend themselves, the Sahwa were virtually defenceless against ISIS. In a pattern reminiscent of Syria, the Iraqi government and ISIS were effectively working in tandem to destroy the Sunni moderates.

Maliki violently repressed a protest movement that broke out in December 2012, leaving few peaceful options by which the Sunnis might change policy, and in December 2013 the Iraqi insurgency went back online. ISIS captured Fallujah (again) in January 2014, and began spreading out. For the first half of 2014, ISIS cooperated with JRTN and other Iraqi groups in administering insurgent-held areas. In June 2014, ISIS conquered Mosul. This is often said to have been an “ISIS invasion from Syria”, but as is made clear above, ISIS had been well into a revival within Iraq by 2011-12—that is why it had spare resources to intervene in Syria in the first place—and ISIS had never been cleared from Mosul, even at its nadir in 2008. ISIS remained deeply embedded in daily life in Ninawa and was an effective “shadow authority” in Mosul for months before it overtly took control of the city, and swept across the central (Sunni Arab) parts of Iraq.

The Ba’athi-Islamist Iraqi groups had largely quit the battlefield and, except for JRTN, were minimally involved in the 2011-14 resurgence of anti-government violence in Iraq; this made them easier to push aside when they did take up arms again. Having allowed cooperation with the other Iraqi insurgents to remove government authority in the Sunni areas, by now ISIS has either destroyed or co-opted the other Iraqi insurgents, and this dynamic has been helped by the ill-advised U.S. policy of aligning with Iran’s tributaries in Iraq to fight ISIS, since helping the spread of Iranian influence has caused Sunnis to close ranks around ISIS as a force to protect against sectarian domination.

Saddam’s Afterlife

Severely damaged in the 2007-09 period, in early 2010, ISIS’s leadership had been cut down very quickly. In January 2010, the U.S. killed Abu Khalaf, ISIS’s most important foreign fighter facilitator, who was based in Syria, leaving a major void in the organization. In March 2010, Manaf al-Rawi, ISIS’s emir in Baghdad, known to his subordinates as “the dictator,” was arrested. Rawi’s information led to ISIS’s leaders, Abu Omar al-Baghdadi and Abu Hamza al-Muhajir, who were killed in April 2010 (it was a month after this that Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi took over). Between April and June 2010, thirty-four of forty-two ISIS leaders were removed. The downside of this was that it left ISIS’s leadership in the hands of the members who were best at operational security and counterintelligence, namely the FREs. This was a significant internal shift, one reinforced by the drying up of the foreign fighter flow because of American disruption and the waning appeal of a failing jihad. FREs were intimately involved in planning both the Syrian expansion of ISIS and the Iraq operations.

The notable FREs within ISIS, revealed by captured documents, are:

- Haji Bakr (real name: Samir al-Khlifawi), a former colonel in an elite Saddamist intelligence unit, who joined ISIS in 2003. Haji Bakr, the overall ISIS deputy, was the key architect of ISIS’s expansion into Syria, where he was killed in January 2014 by Syrian rebels.

- Abu Muslim al-Turkmani (real name: Fadel al-Hiyali): ISIS overall commander in Iraq and Abu Bakr’s de facto deputy. Al-Turkmani had been right at the core of Saddam’s military-intelligence apparatus in Special Forces and is believed to have been close to both Saddam and Douri. When al-Turkmani was imprisoned is unclear but it was certainly well before 2010. Al-Turkmani was reportedly killed in November 2014.

- Abu Abdulrahman al-Bilawi (real name: Adnan al-Bilawi), a former captain in Saddam’s Republican Guards, was highly influential in ISIS by 2004, was imprisoned in 2005 by the Coalition, and was head of ISIS’s Military Council, believed to be the most important ISIS “institution”. Al-Bilawi planned the takeover of Mosul, but was killed just before it went ahead in June 2014.

- Abu Muhannad al-Suwaydawi (real name: Adnan al-Suwaydawi), a Lieutenant Colonel in Saddam’s air force and had been ISIS’s governor of Anbar; he replaced al-Bilawi and was killed in November 2014. (Al-Suwaydawi is frequently misidentified in news reports as Abu Ayman al-Iraqi, who is a separate, much younger person.)

- It was also an FRE, Abu Nabil al-Anbari, a former policeman in Saddam’s regime who was imprisoned with Abu Bakr (i.e. in 2004), who was dispatched to Libya to set up an Islamic State branch in that country, mostly by peeling men away from al-Qaeda’s Ansar al-Shari’a, and using local criminal networks. He was reportedly killed in mid-June 2015 in a very public execution by al-Qaeda.

One can add to that Abu Omar al-Baghdadi, the predecessor of the current “Caliph”, was an FRE, a police colonel, and at a local level ISIS has commanders like Ibrahim Sabawi Ibrahim al-Hassan, the son of Saddam’s half-brother, who was killed by a U.S. drone around Bayji on May 19, 2015.

After Abu Ali al-Anbari (real name: Abd al-Rahman al-Qaduli), the Caliph’s then-deputy, was killed last month, it was revealed that he was not as first thought a Major-General in Saddam’s army, but a long-time al-Qaeda operative who nearly became ISIS’s leader after Zarqawi in 2006. Some have taken this as proof that the FRE influence in ISIS is overstated, but the reality is it does not change much. For one thing, al-Anbari had been a member of Ansar al-Islam and was crucial in bringing al-Turkmani into ISIS. Al-Anbari turns out to be from the “pure” Salafi stream rather than part of the Ba’athist-Salafist current, but he was still incubated under Saddam’s roof.

What this should make clear is that the recent report suggesting that ISIS recruited FREs in 2010-11 and these FREs essentially mounted a coup that turned ISIS into the Ba’athists “Party of the Return” wrapped in a shahada is mistaken. It is clear that the important FREs joined ISIS early, in 2003 and 2004, and did so out of ideological sympathy. ISIS at that time was a foreign-led minority part of the insurgency; those motivated by power joined the Ba’athist-Salafist groups. The very description of the FREs as “Ba’athists” is misleading; they were Islamists long before the Saddam regime ended because of the regime’s policies, notably the Faith Campaign. The contention ISIS “embarked on an aggressive campaign to woo the former officers” after the 2010 killing of ISIS’s leadership simply does not stand up to the timeline. When Abu Bakr was chosen as leader by the Shura Council, by a vote of nine to two, Haji Bakr was one of those voting, as was al-Turkmani. The FREs rose to predominance in a time of peril, but they had been there all along.

The sense that Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi has come from nowhere is one of the things that has allowed this narrative of ISIS-as-a-front-for-the-Ba’athists to take hold, but in fact he was well-known in insurgent circles and to the intelligence services battling the insurgency—even if the latter seriously underestimated him. Abu Bakr emerges out of the milieu of the Faith Campaign: he is a PhD in Islamic Studies, achieved from a University where entry was strictly limited to Ba’ath Party loyalists. Abu Bakr might not himself have been a Ba’athist, but he must have had uncles or other family members in Samarra—a town very loyal to the Saddam regime—who could vouch for him. The direct relationship between Izzat al-Douri and Abu Bakr is unclear but it is probably closer than either would now like to admit. Abu Bakr was imprisoned between January and December 2004 by the Americans, but was released because he did not seem to be a significant danger. Abu Bakr had by 2006 joined Jaysh al-Mujahideen (JAM), a unit formed out of Ba’athist-Salafists, notably Fedayeen Saddam. The likelihood is that Abu Bakr was an AQM/ISIS agent within JAM (ISIS’s infiltration of insurgent units did not start in Syria).

The narrative that ISIS was created at Camp Bucca misses the fact that, while there was proselytization and exploitation of that prison by ISIS, many of the worst detainees were already militant Salafists. The U.S. made many mistakes—not sending enough troops to impose order because of CIA advice (listening to the CIA, full stop, really), not checking the growing influence of Iran in the Iraqi government, not implementing a population-centric strategy to pull people away from the insurgents, and not detaining enough insurgents for long enough—but these merely fed a phenomenon that was already in train long before Western soldiers arrived in Iraq. Analytically, it makes more sense to see ISIS as the afterlife of the Saddam Hussein regime, a cause rather than a consequence of the American-led invasion.

Conclusion

Even if one argues that the FREs are not true believers—and the timeline provides a major problem to this argument—it still leaves a question of who is using whom, and more to the point how much it matters. Just as it doesn’t really make a difference whether Saddam became a true believer or not, since his government ran a policy of enforcing the shari’a internally and alliance with Islamists externally, it is less and less relevant where the line faultline is within ISIS between true believer and cynic: the end result will be the same.

One way that the absorption of the FREs into ISIS can be demonstrated is by the fact that virtually all of the high-profile FREs are dead—yet ISIS’s progress continued. ISIS is arranged to maintain deep continuity; patience is a key doctrine. The FREs’ skills, in counterintelligence and military planning especially, have been imparted, but they are now part of the institutional memory. ISIS isn’t reliant on a regular resupply of FREs. Moreover, ISIS has access to battle-hardened veteran Salafi-jihadists, notably the Chechens. The value of veterans from the Afghan, Algerian, Bosnian, Chechen, and other jihads of the last thirty years is open to doubt—al-Qaeda’s Syrian branch, Jabhat al-Nusra, is stuffed with al-Qaeda veterans, yet it is consistently bested in espionage and combat by ISIS—but they clearly have some value, and ISIS has that, too.

Many actors have influenced and manipulated ISIS’s rise. Iran has played a nefarious role from ISIS’s beginnings, and Assad was determined to make ISIS the face of the rebellion, a project Iran gave its full support to. America’s catch-and-release policy while in Iraq failed to either reform ISIS’s worst, or even keep them off the battlefield. The U.S. withdrawal from Iraq and refusal to intervene in Syria in 2011 or 2012 gave ISIS further time and space to reconstitute itself. The Maliki government’s neglect (at best) of the Sahwa helped create a security vacuum in the Sunni areas that ISIS filled. But still the overriding fact is that Saddam’s policies in his last fifteen years in office prepared the way for ISIS.

Saddam’s Faith Campaign made the Iraqi Sunnis more receptive to Salafism and spread sectarianism, which helps ISIS legitimize its presence. It is true that in some ways the militant Salafists were so strong in Iraq by 2003 because Saddam was so weak—as the regime crumbled these people were already in place to be a successor force. But Saddam had not only ceased all action against the Salafists, but was encouraging them. After the Surge, it was with Douri’s help that ISIS revived. If ISIS as an insurgency—as an army and governing entity—is degraded, it will raise a new series of challenges as ISIS rebalances its resources toward terrorism. But for a constellation of reasons—ISIS’s inheritance from the Saddam Hussein regime primary among them—the day when ISIS’s pseudo-Caliphate is unravelled is quite a long way off.