By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on January 27, 2017

The Islamic State’s June 2014 declaration that the areas it controlled were the restored “Caliphate” was seen by many as a novel development. In fact, “the State” was declared in October 2006. The next month, the predecessor of the Islamic State (IS), Al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia (AQM), dissolved itself, and a month after that the claim to statehood was expanded upon—while being wilfully ambiguous about the caliphal pretensions—in the first speech by the then-emir, Hamid al-Zawi (Abu Umar al-Baghdadi).

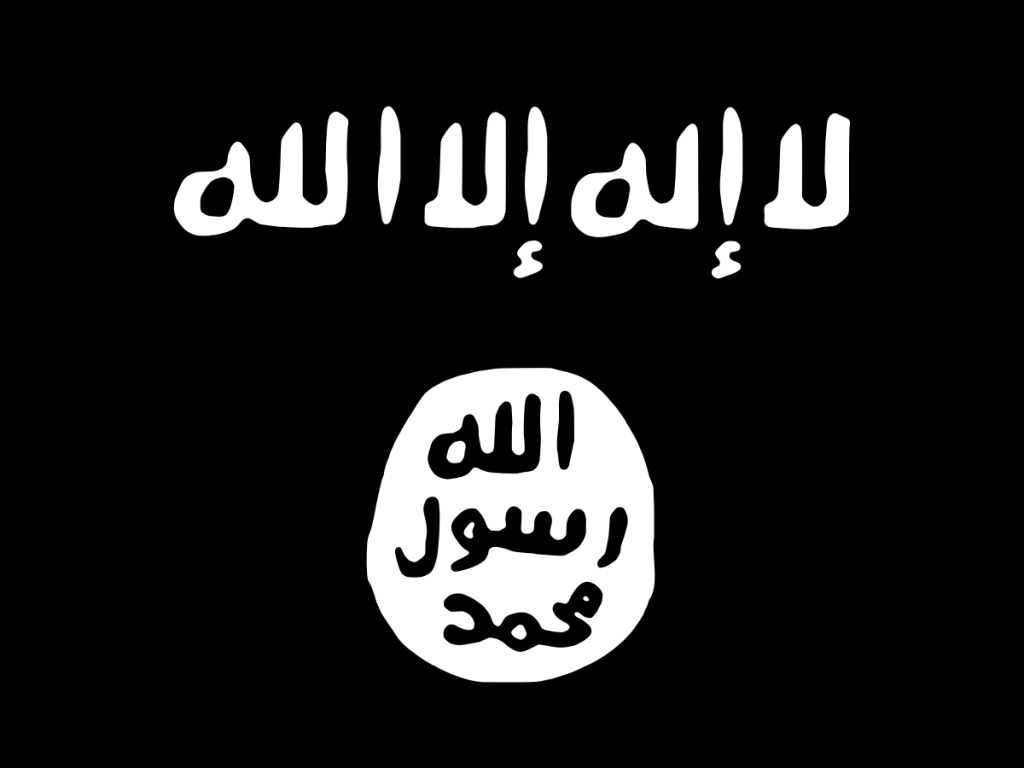

Similarly, though confusion remains on the point, it was in this same period that the symbol of the Islamic State, its black flag, was established, in a ninety-page book issued by Al-Furqan Media Foundation a month after Al-Zawi’s speech, in January 2007, ten years ago this month. The document, “Informing the People of the Birth of the Islamic State” (Ilam al-Anam bi Milad Dawlat al-Islam), was unsigned, but was said to have been “prepared under the supervision” of Uthman bin Abd al-Rahman al-Tamimi, an official of the then-Islamic State of Iraq’s (ISI) “Shari’a Committee” (Hay’at al-Shari’a), part of a structure of administrative bodies that has vastly expanded in the decade since.

THE ISLAMIC STATE SELECTS ITS FLAG

A lot of “Informing the People” is devoted to defending the State project against Islamist critics, both within the Iraqi insurgency and those in the broader region. Al-Tamimi handles the issues of ISI not holding enough territory and not having a developed bureaucracy, of being a “Paper State” as critics would say, and of not having—and not having sought—sufficient Sunni buy-in. Al-Tamimi’s all-purpose answer is to point to the Tradition around the Prophet Muhammad, which tells of the Prophet holding less territory and facing more enemies—pagan and Jewish and even Muslim—when he set up his polity in Medina.

In this way, Al-Tamimi dismisses the practical objections, yet his commentary cleverly does not downplay the ISI’s difficulties. It has always been part of the Islamic State movement’s presentation that it is a lone truth-teller in a region where ruling authorities are notoriously untrustworthy. For this reason, IS was—and remains—very careful that its propaganda is basically honest, even if there are exaggerations at the margins. And by claiming legitimacy from the Prophet’s example, Al-Tamimi is calling on other Muslims to join in order to ensure the State succeeds—turning on its head the objection that not enough Sunnis are on-board. The accusation is returned: those who have not signed-up are the ones in error.

It is in this vein of relying on Muhammad that Al-Tamimi explains the Islamic State’s choice of banner or flag (rayat).

In the set-up to discussing the Islamic State’s flag, in a section on the political justifications for the State declaration (beginning on page 49), Al-Tamimi quotes a press conference President Bush gave on 11 October 2006—four days before the State was formally declared—where the President said, amongst other things, “The stakes are high if we were to leave [Iraq]. It means that we would hand over a part of the region to extremists and radicals who would glorify a victory over the United States and use it … to recruit. It would give these people a chance to plot and plan and attack. It would give them resources from which to continue their efforts to spread their caliphate.” Al-Tamimi comments: “And the liar told the truth about that!”

Al-Tamimi pushes back on the idea the ISI is that incapable of running a State. By confronting the “Zionist-Crusader” forces, says Al-Tamimi, the Islamic State has brought them to “an unprecedented level of weariness and exhaustion”, with reports coming in that the American army is collapsing in various Sunni zones, and people are looking to the ISI. The Iraqi army will evaporate once the Americans are gone, says Al-Tamimi, revealing the true balance of power between the jihadists and the government in Iraq. In terms of legitimacy, Al-Tamimi says Abu Umar has the support of the theologically competent and other eminent Muslims, those IS would come to call ahl al-hall wal-aqd (lit. “those who loose and bind”), jihad requires a single emir to direct it, and in any case legitimacy only attaches to those fighting to uphold the deen, while all the other notionally Sunni actors are collaborators with “the plans of the American Cross”.

The post-American situation will allow Sunnis to see the dangers of remaining fragmented and rally them around the true monotheists. Here (pp. 56-7) Al-Tamimi quotes one of the Islamic State’s favourite Qur’anic verses: “Hold fast to the rope of God, all of you, and do not be divided” [3:103]. Various other Qur’anic verses and Hadith are quoted on the duty of obedience and gathering under the command of a single Imam. “The banner is the meaning [or intention or purpose]” (Fal-rayat hee al-qasd), says Al-Tamimi. Fighting for tribe and nationalism is intolerable next to the demands of the faith: the rightful Imam is to raise “the Banner of the Eagle” (Rayat al-Uqub), the banner carried by the Prophet himself that is often known as the Black Standard, and it thereupon becomes obligatory to pledge allegiance (bay’a) to the Imam, to follow him into battle against the unbelievers under this banner. A Hadith from Ibn Umar, one of the Prophet’s Companions (Sahaba), is quoted to reinforce the message that Muslims owe obedience to such an Imam, else they will suffer damnation after death for remaining in jahiliyya (pre-Islamic ignorance).

When the first picture of the Islamic State banner was released in January 2007 by Al-Fajr Media (Dawn Media) it showed a black flag you can see at the top of this post, with a white line of text at the top reading, “There is no god but God” (la ilaha illallah), and a white circle in the middle—meant to represent the seal the Prophet Muhammad used—with black text in it reading, “Muhammad is the Messenger of God” (Muhammad rasul Allah).

IS’s founder, Ahmad al-Khalayleh, the Jordanian jihadist universally known by his kunya, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, had set the pattern for boldness—for thinking bigger than even Usama bin Laden—and Islamic State was being true to its founder’s audacity in claiming the Prophet Muhammad’s personal banner for its own. But there was a catch. There is no evidence Muhammad ever fought under this standard.

A TROUBLED HISTORY

The problem is two-fold.

First, there is the specific design of the Islamic State’s flag, which is, as William McCants has noted, “unique, different from every other attempt to replicate the Prophet’s flag”. And we know where IS got the idea. At the same time as “Informing the People” was published and Al-Fajr’s picture of the flag was released in January 2007, an anonymous IS supporter wrote an essay, “The Legitimacy of the Banner in Islam”, explaining that the design was drawn from the seal of the Prophet used on a letter of Muhammad’s housed at the Topkapi Palace in Constantinople, and that the seal on this letter was genuine because it comported with historical descriptions of the seal used by Muhammad.

In reality, this letter—supposedly found by a Frenchman, Etienne Barthélémy, and addressed to Al-Muqawqis, calling on the Coptic Christians to convert to Islam before the Arab conquest of Egypt—is a European forgery from the middle of the nineteenth century. Despite the Ottoman Sultan paying an enormous amount of money to purchase the letter in 1858, Orientalist scholars were casting doubt on its authenticity—and those “discovered” in its wake—from the early 1860s, and by the first decades of the twentieth century they were decisively discredited.

Second is a problem that is far more serious, and will already be apparent to anyone who has read the “revisionist” scholarship on Islam’s origins that began with John Wansbrough and Patricia Crone in the 1970s, which has now even won-over Crone’s great antagonist Fred Donner: there was no Islam during Muhammad’s life.

The monotheistic creed of the Arabs who conquered the Near Eastern and North African lands of Byzantium, and the Persian Empire, only began separating into something distinctive in the 690s AD and Islam in a form recognisable to us crystalised around 800 AD. The “double Shahada”, as Donner calls it, the profession of faith that includes both “There is no god but God” and “Muhammad is the Messenger of God”, only came into use in the 690s, imposed from the top-down by the Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Malik. The first decade of Abd al-Malik’s reign was marked by a particularly ferocious bout of civil war, where his enemies had hit upon the “Muhammad card” as a weapon to challenge him: the rebels claimed to be living out the Prophet’s example better than the Caliph. It was a momentous innovation, since, to that point, Muhammad had been all-but forgotten. But such political warfare had a potency that Abd al-Malik recognised, and as part of his consolidation of legitimacy after militarily crushing the rebellion, he annexed the rebels’ program.

Given this history, it is clear why Rayat al-Uqub is not mentioned in the Qur’an: the Qur’anic text was written before the “double Shahada” was invented.

(It should be noted that the origins of the Qur’an are bitterly contested. Wansbrough argued that it was a late creation: that the reason there are no extent versions of the Qur’an dating to Muhammad’s lifetime is that they never existed. The text of the Qur’an itself gives precious little evidence to associate the book with someone called Muhammad. Nonetheless, the text also provides evidence of Late Antique origins, and the way later Muslims handled the Qur’an—maintaining and trying to interpret passages they clearly did not understand—can sustain the argument that it did originate in Muhammad’s time.)

THE TRUE ORIGINS OF THE ISLAMIC STATE’S FLAG

Where, then, did the idea for the Rayat al-Uqub come from? The nineteenth-century forgers must have been working from something and the Ottoman Caliph must have had some reason to believe them. The answer is the Hadith.

As the anonymous author of the essay mentioned above documented extensively, the claim that Muhammad flew a banner corresponding to the design of the IS flag as he went into battle in the 620s and 630s AD is repeated multiple times in the Hadith, and all of these Hadith have impeccable isnad (chains of reporting). Which is precisely the problem. As Tom Holland puts it in his book on Islam’s origins, In the Shadow of the Sword, “Rather as in an Agatha Christie novel, where it is invariably the suspect with the most ornate alibi who proves to be the murderer, so similarly, in the field of Hadith studies … there [is] no surer mark of fraud or distortion than a really exacting attention to detail [in isnad].”

As to where and when the Hadith about the Black Banner originate, we can get some clues by looking at them:

- “When the Black Banners come from Khorasan go to them, even if you have to crawl on snow, for among them is the Khalifa from Allah, the Mahdi” [Ibn Maja (c. 824 – 889 AD), compiler of the last of the six authentic collections of Hadith, according to Sunnis].

- “Surely Black Banners will appear from Khorasan until the people [under the leadership under this banner] will tie their horses with the olive trees between Bayt-e-Lahya and Harasta [supposedly meaning Jerusalem]” [Kitab al-Fitan, c. 820 AD].

- “A group of people will come from the East with Black Banners and they will ask for some ‘Khayr’ [assistance, leadership, stability], but they will not be given what they ask for [the Arabs won’t respond to them]. So, they will fight and win against those people [the Arabs causing fitna or strife]. Now, they will be given them what they asked for [leadership and responsibility], but they will not accept it until they hand it over to a person from my Ahl Bayt [Imam Mahdi] who will fill it [the Earth] with justice, just as they [the tumultuous Arabs] filled it with oppression. So, whoever of you will be alive at that time should come to them [the Mahdi and the people from the East with black flags] even by crawling over snow” [Ibn Maja].

- “‘Three will fight one another for your treasure, each one of them the son of a caliph, but none of them will gain it. Then the Black Banners will come from the East, and they will kill you in an unprecedented manner.’ Then he mentioned something that I do not remember, then he said: ‘When you see them, then pledge your allegiance to them even if you have to crawl over the snow, for that is the Caliph of Allah, Mahdi’” [Ibn Maja].

The notable thing about all of these Hadith is they have the armies bearing the Black Banners coming from Khorasan (or “the East”) and a demand that people follow this movement because it will do away with injustice, which is the self-presentation that the Abbasid dynasty gave of the revolution that brought it to power against the Umayyads in 750 AD.

The Abbasids had organised their revolution in Khorasan, mostly modern-day Iran and Afghanistan, harnessing the utopian, millenarian, and apocalyptic yearnings among the Alids (those who claim descent from Imam Ali), essentially Shi’is, and the Zoroastrian remnants in the rural hinterland, promising to bring light where the Umayyads had brought darkness, and swept in from the east, under their Black Banners, overwhelming the Umayyads in their Syrian stronghold.

The Abbasid difficulty once in power was that to maintain the Empire’s hold on the territories in the Middle East and North Africa, it could not radically shift ideological ground, so it kept the fundamentals of the Umayyad Imperial ideology in place—which left those who had provided the wave the Abbasids had ridden to power feeling betrayed. But the battle was not over because the Abbasids were different: the distinctly Arab and Mediterranean-focused Umayyad Imperium became a Persianate Empire with its centre of gravity further east, in Mesopotamia. (Baghdad was founded in 762 AD and remained the capital for half-a-millennium.)

In Mesopotamia, the crucible centuries earlier of Rabbinic Judaism, the process began to repeat with a still-fluid Islamic creed indelibly stamped with its Judeo-Christian origins. The mix was thickened by drawing on intellectual currents from Persia, since the scholars were mostly Persians. A class of ulema (or jurists) began constructing the great corpus of the Sunnah, modelled on the Talmud, which recorded and codified the teachings and sayings of the Prophet Muhammad in the Hadith to serve as the model for Muslims to follow. The implication was that the Caliph could be judged by the standards of the Sunnah, too, and the framework of Islamic history would in many ways become the contest between the Throne and the jurists.

The charge to this dynamic in the early decades of the Abbasid Caliphate was that it gave Persians, now elevated to elite status, a mechanism for challenging their Arab overlords for control of the Empire. As was to be discovered, two could play that game. If ulema rulings could be found to obstruct the Caliph, they could just as easily be found to serve him, and over time the jurists would become decisively the servants of the Caliph.

Note the timing of the Hadith about the Black Banners: the ninth Christian century (third Islamic century), seventy and more years after the Abbasid Revolution, during the period of the Islamic “golden age” (c. 750 – 861), when the Abbasid regime is firmly entrenched and setting the intellectual tone—even sponsoring large amounts of intellectual produce in the Empire, obviously intended to redound to its own glory. Sunan ibn Maja, where many of the Black Banners-related Hadith are recorded, is particularly notable in this regard: widespread in the Abbasid heartlands of Iran, it was much less well-known beyond that. And this is the context the Black Banners’ Hadith should be seen in, the post-hoc effort to legitimise the Abbasid Revolution and Caliphate.

APOCALYPSE NOW?

As a final note. The Hadith about the Black Banners have an apocalyptic association, and the Islamic State has played with eschatological themes, notably over Dabiq, the village in Syria that is said by the Hadith to be the place where End Times will begin. McCants, for example, says directly: “The Islamic State was signaling that its flag was not only the symbol of its government in Iraq and the herald of a future caliphate; it was the harbinger of the final battle at the End of Days.” In late 2007, ISI’s Chief Judge, Abu Sulayman al-Utaybi, appeared to vindicate this view, defecting, and going to Pakistan to complain to Al-Qaeda’s leaders that Al-Zawi and his deputy, Abdul Munim al-Badawi (Abu Hamza al-Muhajir), were taking ISI down a destructive road because they were besotted with apocalyptic fantasies.

The evidence, however, is strongly against any apocalyptic understanding of the Islamic State. Juhayman al-Utaybi, the zealot who seized the Grand Mosque in Saudi Arabia in November 1979, had a legitimately apocalyptic vision: despite a well-organised operation to seize the mosque and ample preparations for it, the rebels ran out of food in under two weeks because they did not stockpile enough; they did not think they would need it. The Islamic State does not manage resources in this way; the group is prepared for the long haul and builds its terrorist-revolutionary strategy around the expectation of cyclical hardships that will purify the ranks to grant them ultimate triumph very much on the temporal plain, not expectations of End Times’ imminence. The IS movement’s leadership doubtless believes there will be an End of Days—it is in the Qur’an, after all—and is quite happy to instrumentalise such beliefs for recruitment, but the leadership’s expressed vision back to Al-Zawi’s days, and the scrupulous bureaucratic use of resources tell of a menacingly reality-based insurgent program.

“Informing the People” is itself an example of this. The document was issued just as the American “Surge” and the Iraqi tribal “Awakening” (Sahwa) was beginning, and almost exactly three years later, in the aftermath of these forces apparently defeating the Islamic State movement, a similar document, “A Strategic Plan”, was produced assessing what had happened and where the jihadists’ strategy needed tweaking. In neither publication, which are larded with ideological explanations for the Islamic State’s behaviour, is there even a hint that the group is relying on the heavens, beyond the usual caveat of Islamic predestination, that nothing can happen save what God intends. The focus is about handling the tribes and the necessary tactics to eliminate their enemies, namely the Americans, the Iraqi government, and the Muslim Brotherhood.