By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 2 October 2025

The Fascization of the Enemy Image in Soviet Visual Propaganda at the Beginning of the Cold War Period (1946–1964)

E. A. Fedosov

2017

Bulletin of Tomsk State University [Vestnik Tomskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta]

[The original Russian text from which this rough translation was made is available here—KO]

Carried out within the framework of the project “Man in a changing world. Problems of identity and social adaptation in history and the present” (Grant of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 14.B25.31.0009).

The experience of the fascization of the enemy image in the visual propaganda of the USSR at the initial stage of the Cold War is considered. The textual and visual content of propaganda posters and newspaper caricatures devoted to international themes is examined for the presence of concepts and symbols associated with fascism. Based on the results of quantitative and qualitative analysis of facts, the political forces and social phenomena are identified which, in the mass consciousness, were most likely to be interpreted as fascist.

____________

In the victorious spring of 1945, the Red Army dealt a mortal blow to the Nazi Third Reich. Soon afterward in Nuremberg, it seemed that in accordance with the will of all humanity and forever, its ideology and practice were condemned. However, in our own day attempts to rehabilitate fascism are observed with increasing frequency, and the influence of the so-called ultra-right radicals is growing. Moreover, this is happening in countries that actively declare their adherence to the ideals of modern democracy. In today’s difficult conditions of substitution of ideological reference points and their transformation under the realities of information wars, it seems expedient to analyze what exactly, how, and why in our country was associated in the mass consciousness with the fascist threat already in the postwar period. In this regard, great interest is aroused by the Soviet propaganda experience of the Cold War era.

The very presence of antifascist rhetoric at the next turn of the global confrontation between the USSR and the West was far from accidental. For the communists, the classical definition of fascism remained the one voiced back in 1934 at the XIII Plenum of the Executive Committee of the Communist International: “the open terrorist dictatorship of the most reactionary, chauvinistic, and imperialistic elements of finance capital” [1. P. 34]. The connection between capitalism and fascism was also pointed out by the Western researcher W. Wippermann: “…the fact is that fascist parties arose and grew on the soil of capitalism, that they possessed a special attraction for certain strata of capitalist society, that capitalist circles were prepared to provide the fascists with political and financial support” [2]. Some contemporary Russian philosophers also develop the idea that fascism is genetically derived precisely from the liberal-bourgeois egocentric doctrine of competing “free individuals” [3]. It “grew out of the idea of competition and the suppression of one another—not at the level of the individual, but of the race” [1. P. 26]. At the same time, the ideology of the “single bundle” (“fascio”) in the form of the domination of a nation or race should be considered also as one of the forms of reaction to the disunity of capitalist society [Ibid. P. 25]. Therefore, one or another degree of fascization of the image of the capitalist-enemy appears not only ideologically, but to some extent civilizationally predetermined, and thus highly relevant for study.

Another point that should be noted is that, in addition to distinctive ideological features such as anti-communism, corporatism, chauvinism, and militarism, the fascist movements of the twentieth century are marked by a set of symbolic traits that formed a “specific political style” [2]. In other words, despite all the discussions about which particular regime should be considered fascism, Nazism, national socialism, simply some junta or “reactionary clique,” the external image sometimes characterizes its features much more strongly than actual policy. The point here is not the correctness of such identification. What is important is that attributes and symbols of fascist origin are sufficiently recognizable and semantically loaded so as to be actively employed in counter-propaganda.

In this connection, let us turn to the sources which, at the initial stage of the Cold War, most fully carried out the task of figurative-symbolic discrediting of the ideological adversary, namely Soviet posters and caricatures. The purpose of the article is, on the basis of these materials covering the period 1946–1964, to identify the political forces and social phenomena that were ascribed fascist features. To this end, 630 propaganda posters and 848 caricatures from the newspaper Pravda on international themes were examined. The extensively represented image of the enemy in them was analyzed for the presence of symbols which in the Soviet mass consciousness were most likely to be interpreted as fascist: the swastika, the Nazi salute, the “imperial” eagle-vulture, elements of German wartime uniforms, as well as the personages of Hitler and his associates. In addition, the direct mention of fascism and concepts associated with it in the textual part of the sources was taken into account.

By the beginning of the Cold War the above-mentioned set of symbols was, of course, by no means new for Soviet visual propaganda, especially in its satirical part. Thus, already in 1923, “the split of the German fascists” in the caricature of the same name by B. Efimov was likened to the divergent rays of a swastika, one of which personified a grotesque-looking Hitler [4. P. 32]. Subsequently, the caricaturist who created it recalled that with the appearance of fascism on the historical stage, Soviet artists did not tire of “branding the barbarism and monstrosity of the fascists, exposing their brazen pretensions and shameless demagogy, mocking the stupidity and obscurantism of racist ideology” [5. P. 14]. To this it should be added that antifascist rhetoric was spread not only to the corresponding regimes, but also to the capitalist countries as a whole, as well as to traitors to the cause of revolution—“Trotsky and his bloody fascist gang”.[1] The exposure of the enemy was carried out not only by the method of satire, which evoked bitter laughter and contempt. Completely different emotions were targeted, for example, by the poster of P. Karachentsov “Fascism is hunger, fascism is terror, fascism is war!” (1937). The formula laid down in this slogan was visualized not by the typical image of the time of a beast-like German stormtrooper, but by images arousing sympathy: a destitute woman and child, behind whom march men in brown uniforms. Despite minor political fluctuations caused by the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact in 1939, the negative image of fascism firmly entrenched itself in the Soviet consciousness. Thus, the historian and veteran L. D. Efanov well remembered the words of his teacher, which precisely illustrated prewar moods: “Because we have concluded a treaty with Germany, the matter does not change. Remember, fascists are fascists…” [6. P. 77]. Much is already known about the specifics of visual propaganda under the conditions of the Great Patriotic War. Let us merely note that, judging by posters, it is clearly visible how, at certain stages, fascism, while being purely a political category, acquired certain nationally colored traits, and the earlier caricature-metaphorical language of its discreditation at times became more realistic [7. P. 192–193].

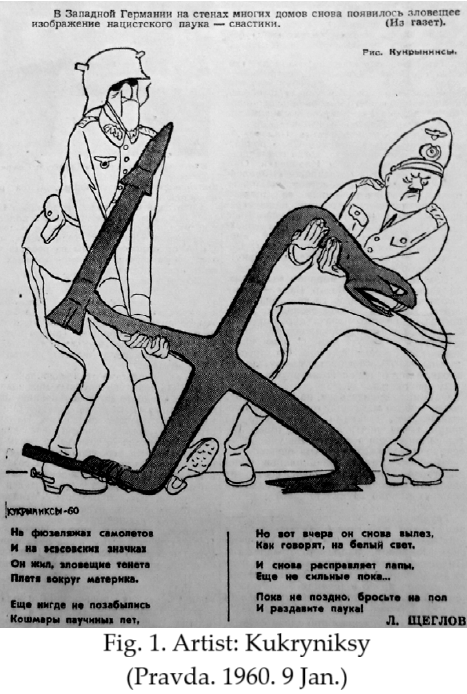

What, then, were the prospects for using the theme of fascism in propaganda after victory? The overall quantitative data testify to the scale of its dissemination. Thus, for the period 1946–1964, fascist symbols are found in approximately 31% of caricatures and in 6% of posters on foreign policy themes. The latter figure should not be considered insignificant, since poster materials were intended primarily to depict the positive hero and formulate motivational slogans. And the fact that even in them various antagonistic images were 39 times endowed with references to fascism is quite telling. Among the corresponding symbolism, the most widespread and universal was the swastika. It is present in 189 caricatures and 34 posters, exposing a fairly diverse range of political forces. In 1960, to this “Nazi spider,” once again noticed on the walls of houses in West Germany, Pravda devoted an entire plot-warning: “On the fuselages of airplanes and on SS badges it lived, weaving sinister webs around the continent. Nowhere have the nightmares of the spider years been forgotten, but just yesterday it again crawled out, as they say, into the light of day. And once more it spreads its legs, not yet strong… Before it is too late, throw it to the ground and crush the spider!”—the lines of L. Shcheglov were illustrated by a drawing of the Kukryniksy, in which two militarists in uniforms resembling those of the Wehrmacht drag a broken snake-like swastika [8. 9 Jan.] (fig. 1). One of its rays was executed in the form of a rocket, which expressed the idea of the particular danger of the rebirth of fascism in the nuclear age against the background of growing international tension at the beginning of the 1960s.

The earliest visual-satirical responses to the possibility of the development of a new conflict also resounded from antifascist positions. The first of the caricatures, published in Pravda in 1946, on behalf of “international democracy” branded as likely warmongers not the West as a whole, but precisely the fascist-leaning European right: “They do not walk now in uniformed clothing, they are not preparing to set the Reichstag on fire, but somewhere in passing they will make a speech, and they will be answered by a many-voiced chorus: Yalchin and Anders, Franco and the hitosos…”[2] [9. 1 May] (see fig. 2). It should be noted that the Spanish dictator mentioned here was depicted with a swastika and an iron cross. But while Franco in the eyes of Soviet propaganda had already historically been the embodiment of the fascist, the onset of the Cold War began to assign this unseemly role to other politicians as well. Thus, at the very end of 1947 there was created, dedicated to the 30th anniversary of the Soviet armed forces, the satirical poster by B. Efimov and N. Dolgorukov “The warmongers of a new war should remember the shameful end of their predecessors! (N. Bulganin).” In it, among the warmongers appeared the recently allied General de Gaulle, in whose hand there was something like a standard made up of a plaque “crusade against the USSR” and a swastika. This same fascist sign is visible on the alpine hat placed by the artists on a caricatured figure symbolizing, obviously, German nationalism. Remarkably, all these figures, led by Churchill, were climbing out of a huge sack with the emblem of the dollar. In essence, this piece of propaganda predetermined the main logic of the fascization of the enemy image in the period of the Cold War under review: the West, united by the ideology of anti-communism and nourished by American capital, becomes a favorable environment for all sorts of ultra-right elements and thereby exposes its own gravitation toward fascism.

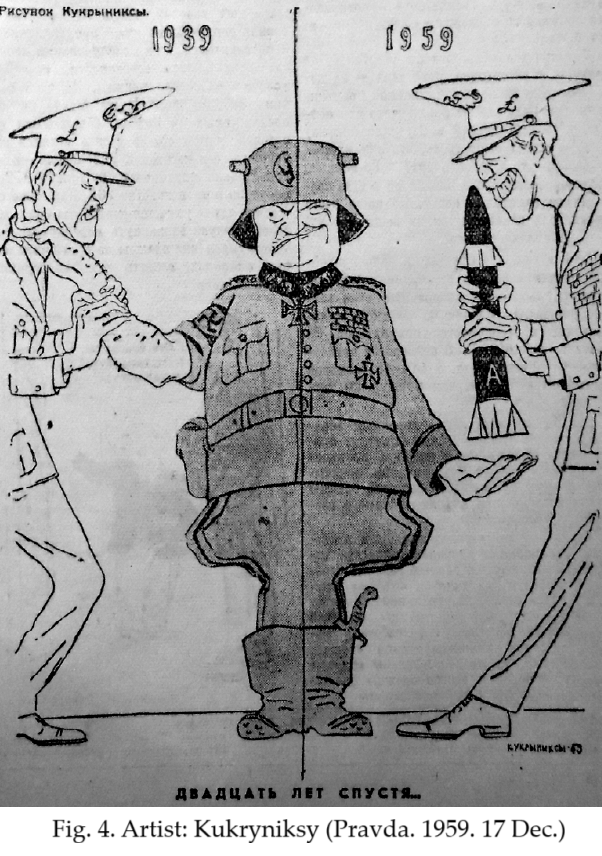

In the above-mentioned poster, for the first time within the framework of the Cold War there was conveyed the idea of the beaten “predecessor,” which, on the one hand, glorified the Armed Forces of the USSR, and on the other, provided a pretext for depicting caricatured fascists of the past. Subsequently, in propaganda pieces on this theme there were usually juxtaposed the images of a jaunty, spirited Soviet soldier or sailor and the pitiful interventionists, either caught on bayonets or floundering in the sea.[3] Thus was expressed admonition to potential aggressors. With the aid of an interesting metaphor this was most directly conveyed in the work of R. Matusevich Forget-me-nots to the warmongers (in Ukrainian, 1948), where the recent leaders of the Axis countries appeared in the role of a “bouquet.” A red fist extended it to contemporary Western politicians, among whom Franco again stood out especially with a swastika and iron cross on his uniform (see fig. 3). The method of historical allusion was employed in the satirical posters of B. Efimov and N. Dolgorukov: An Old Song in a New Way (1949), based on the parallel between the North Atlantic Alliance and the Anti-Comintern Pact; On Their Own Head (1960), in which NATO leadership “fools around” with an old fascist helmet, trying to cover a swastika on it. In a similar way the character of relations within the organization was mocked. Thus, in a Pravda caricature Twenty Years Later, a fascist general holds a Briton by the throat in 1939, but already in 1959 the Briton, smiling, is ready to hand the German a nuclear missile through the channel of alliance with the Bundeswehr [10. 17 Dec.] (fig. 4). Or after the signing of the treaty on cooperation between France and the FRG in 1963, de Gaulle in the eyes of the caricaturist M. Abramov became another “French heel” to the German army boot, in exactly the same way as the collaborator-minister Laval in 1943 [11. 20 Feb.].

If we speak of personalized shadows of the fascist past, then in general for 1946–1964 Hitler, his associates, and allies are depicted in posters 17 times, in caricatures—71 times. And often they appeared not only in a comical, but in a rather eerie guise. A vivid example of this is the plot by the Kukryniksy Parade of the NATO Command Staff. In it, in a single formation, the generals of the Wehrmacht who survived and received posts in the Alliance stand together with the dead fascist leaders before the Pentagon emissary, into whose mouth is put the phrase: “It is a pity that many of them did not survive; they might have come in handy” [12. 17 Dec.]. In infernal style the artists also exposed the ultra-right West German newspaper Nationalzeitung und Soldatenzeitung, likening it to a mouthpiece in the bony hands of Goebbels, preaching from the grave [11. 6 Dec.]. Obviously, all this was intended to convey the idea that cooperation with former Nazis or an appeal to their ideological legacy is the most ruinous political path.

Such were the most universal regularities of the fascization of the enemy image at the stage of the Cold War under consideration. But each specific political precedent in its own way fixed upon the adversaries of the USSR the symbolic shades of fascism, manifested at different times and with varying intensity. Let us examine them in somewhat more detail.

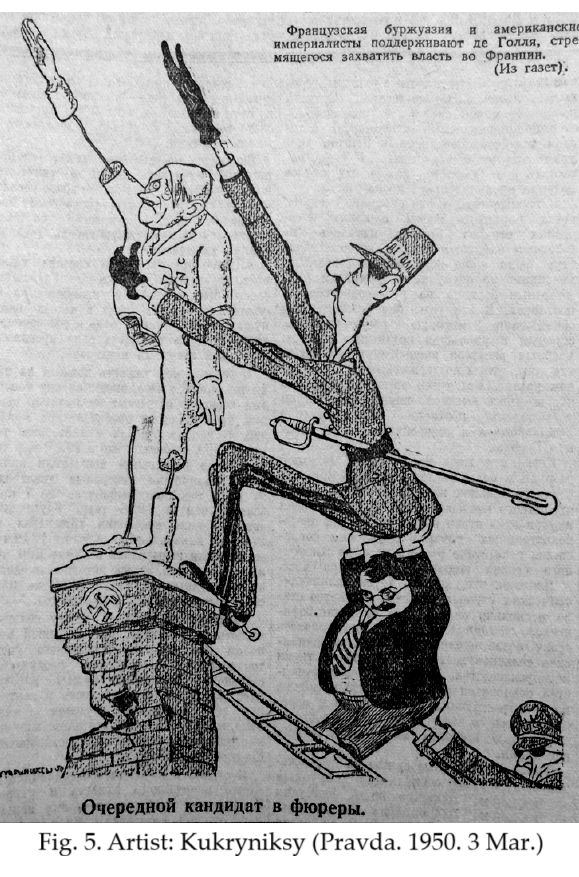

It was already mentioned above that among the “warmongers” of the Cold War the first bearer of fascist symbolism (not counting Franco, who had been endowed with it since the 1930s) turned out to be de Gaulle. In a caricature of one of the issues of Pravda from 1950, the French general striving for power was already directly called the “next candidate for Führers,” depicted with his hand raised in the Nazi salute and comically climbing onto the shattered statue of Hitler with the help of his internal supporters and external (American) patrons [13. 3 March] (fig. 5). At the same time, characteristic for the mid-1950s were plots in which the national symbols of France—Marianne or the Gallic rooster—seemingly conflicted with fascist ones [14. 21 Oct., 31 Oct., 22 Nov.]. This illustrated the prospect of Western states signing various military agreements that led to the remilitarization of the FRG and, in the eyes of Soviet propaganda, bore a threat above all for the French. In the commentaries to these caricatures there was once again reflected the viewpoint that all this was being done under the pressure and in the interests of the imperialist circles of the USA and partly Britain. For the report on antifascist rallies in Paris in 1958 there was also prepared a drawing based on contrast, “Fascism raises its head…” [15. 18 May]. In it, a resolute monumental woman-Republic in the famous Phrygian cap opposes petty caricatured military and governmental reactionaries who try to impose upon her a general’s dictatorship, presented in the form of a stone bust—the head of de Gaulle. In the early 1960s the image of political life in France became more intensively fascisized by the denunciation of the ultra-right organization OAS, which unfolded its terrorist activity, as was thought, with the complete indulgence of the authorities. From December 1961 to May 1962 Pravda published 7 caricatures on this theme, in 5 of them the swastika is present.

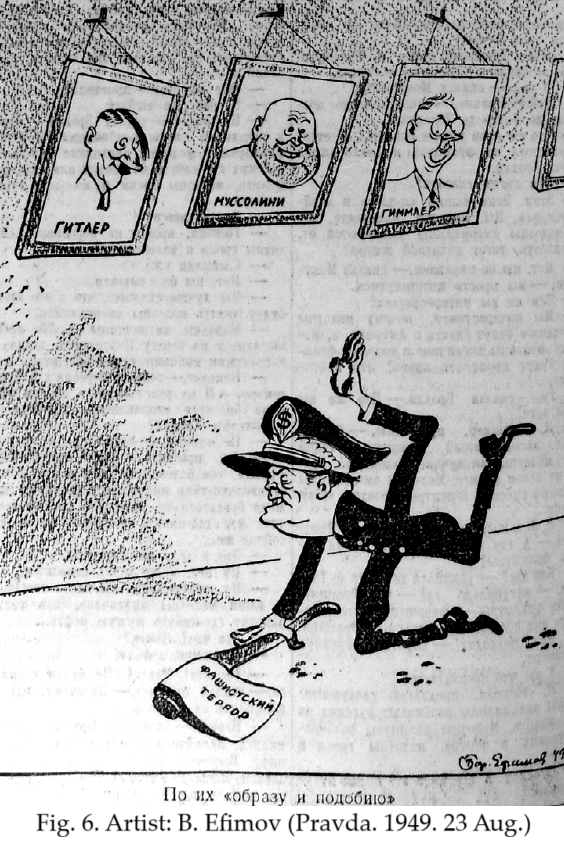

Returning to the beginning of the Cold War, one cannot fail to mention the experience of the fascisation of the image of Yugoslavia in the person of its leader I.B. Tito, which represented one of the sharpest turns in the history of Soviet propaganda. In the memoirs of B. Efimov, a direct witness of many ideological changes in our country, a particular episode is highlighted when, in 1949, the editor of Pravda L.D. Ilichev, “to no small astonishment, asked to urgently draw for the next issue a caricature of Tito entitled ‘The Defector’” [16. P. 403]. The editorial assignment was carried out, and in the newspaper of 13 August 1949 readers saw a drawing with the long title “The defector from the camp of socialism and democracy to the camp of foreign capital and reaction” [17. 13 Aug.]. A grotesque-looking Tito rushed towards Truman, Churchill, and Franco, which, it must be said, still looked relatively neutral. But already ten days later B. Efimov, in the caricature “In Their Image and Likeness,” depicted the Yugoslav marshal in the form of a swastika, which saluted the portraits of Hitler, Mussolini, Himmler, and held an axe inscribed “fascist terror” [Ibid. 23 Aug.] (fig. 6). And soon, thanks to Kukryniksy, the former closest ally began to be called “Titler” [Ibid. 4 Sept.]. Such visual materials, where Tito, accused of betrayal, was by means of symbolic devices or in direct text called a fascist, were published especially often in Pravda in 1949–1950 (10 times), after which, despite the continuation of the Soviet-Yugoslav conflict, newspaper caricatures almost ceased to turn to this theme. Meanwhile, with the beginning of the Korean War and the growth of anti-communist hysteria in the West, new vivid contenders for the role of fascism’s successors appeared in Soviet satire.

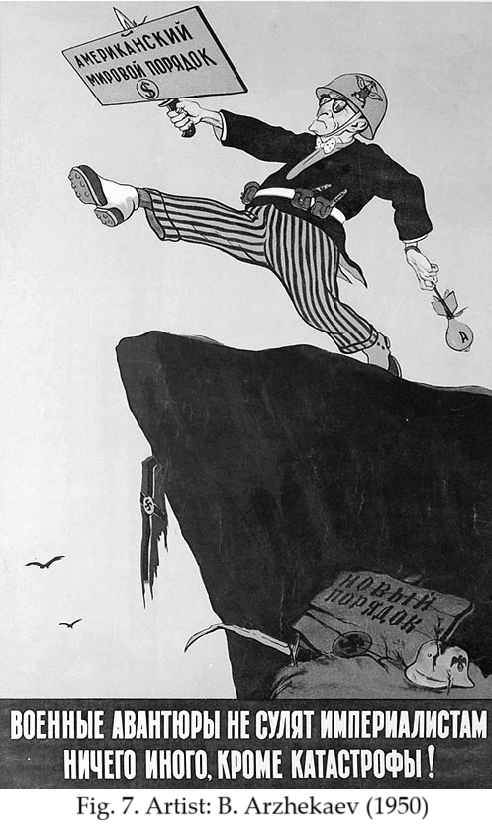

If each plot created by caricaturists is considered as an interaction of several anti-heroes at once, characterising some hostile phenomenon, then one can discover that American images and symbols are clearly adjacent to fascist ones in 131 drawings published from 1949 to 1964. In this way an understanding was formed that in the Western bloc fascism is supported in the interests of the ruling and, especially, the military circles of the USA.[4] In fact, they themselves were represented as continuers of a quite definite political way of thinking. Thus, at the basis of the satirical poster “Military adventures promise the imperialists nothing but catastrophe” (1950) lay the comparison of the “American world order” with Hitler’s “new order,” whose inglorious end was symbolised by a torn fascist banner and a pierced helmet (fig. 7). No less vivid an example of this tendency is the agitka of N. Dolgorukov “American ‘freedom’—a prison for the people” (1951). It is built as several plots exposing the social sores in the USA. Among other things, in them there is a militarist literally pouring “aggressive psychology” into the head of a young half-fascist-half-gangster. Below, however, a sufficiently optimistic conclusion-slogan is made: “Fascisation of America is going at full speed, but the last word will be spoken by the people!”. As a metaphor of the “Hitlerite path” and the “old fascist road,” as well as with a swastika and the physiognomy of the Führer, the actions of the American military in the last years of the Korean War were marked in Soviet visual propaganda.[5] Subsequently, the features of fascism in the American style were symbolically attached to groupings inclined to militarist or racist rhetoric. In particular, in 1962–1963 their political nickname—“the mad”—was played upon through analogy with the “mad” Hitler and his Nazi pogromists [11. 4 Dec.; 19. 14 Dec.].

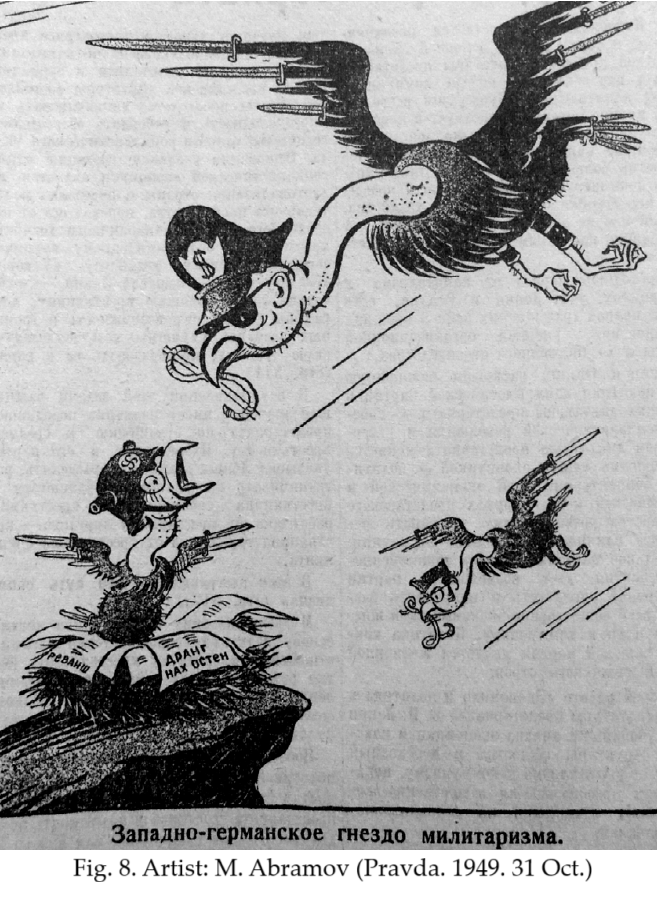

With the formation of the FRG in 1949, the most stable context for the fascisation of the image of the enemy appeared in Soviet visual propaganda. The scale of this tendency is clearly demonstrated by quantitative data: in 87% of Pravda’s caricatures of the West German regime, fascist symbols were present. At the same time, from 1952 to 1958 such an image of it remained practically without alternative. In essence, already the very first drawings, published in the autumn of 1949, for many years laid the foundations of the Soviet perception of the political role of the FRG: a puppet state, headed by a fervent anti-communist—Chancellor Adenauer, with the financial support of its overseas patrons, makes plans of revanche directed against the socialist camp and threatening peace as a whole. A symbolic expression of this was the “government platform” made of the dollar sign and the swastika, the “restoration” by local parliamentarians of the broken statue of Nazism, as well as the curious image of a still unfledged German vulture in a Wehrmacht helmet, which is “fed” by American and British hawks [17. 11 Sept., 22 Oct., 31 Oct.] (fig. 8).

The central place in the satire on the policy of West Germany was occupied by the emphasis on militarism. In general, during the period considered in the article, it was not even the swastika (appearing 138 times), but precisely parodies of the uniform of Hitler’s armed forces that became the main method of symbolic exposure of the remilitarisation of the FRG—in total 150 such images were published. Usually these symbols were combined both with each other and with some others, less common but also carrying a fascist shade. This is especially vividly noticeable in the caricature of the Kukryniksy “To Western Europe—from the overseas uncle” [20. 1 Jan.], in which the West German state is personified by a soldier in Wehrmacht uniform with a swastika on his helmet and a portrait of Hitler. His right hand is raised in the Nazi salute. In a significant part of the drawings, Adenauer personally appears in such a form. The fascisised image of the chancellor proved so emblematic that at times it also appeared in political posters.[6]

It is obvious that the logic of the plots connected with the FRG proceeded from the conviction that any attempts to increase military power (violation of the condition of the demilitarisation of Germany) together with the orthodox rejection of socialism and, as a consequence, the non-recognition of the GDR (violation of democratisation) almost automatically mean the trampling upon another most important post-war principle—denazification. Does this testify to the birth in Soviet propaganda of one of the most powerful political or even national stereotypes? It must be said that with all the semantic colouring of the symbolic series of caricatures, in the commentaries to them the political life in the FRG is directly identified with fascism no more than a dozen times.

The prevailing formulation was “the Bonn revanchists,” which, although associated with the spirit of German militarism, in essence reduced the image of the enemy to the level of a local grouping in the person of the capital’s elite and its supporters. At the same time, in the press and in agitational posters the image of another, Eastern Germany, friendly and peace-loving, was being formed.[7] It is noteworthy that on the eve of the 18th anniversary of the beginning of the Great Patriotic War in Pravda there was published a drawing by M. Abramov, “Peace Friendship Frieden Freundschaft,” in which the handshake of a Soviet and an East German worker was a blow against the American militarist, the capitalist “atomshchik,” as well as the revanchist outwardly resembling Hitler [10. 21 June].

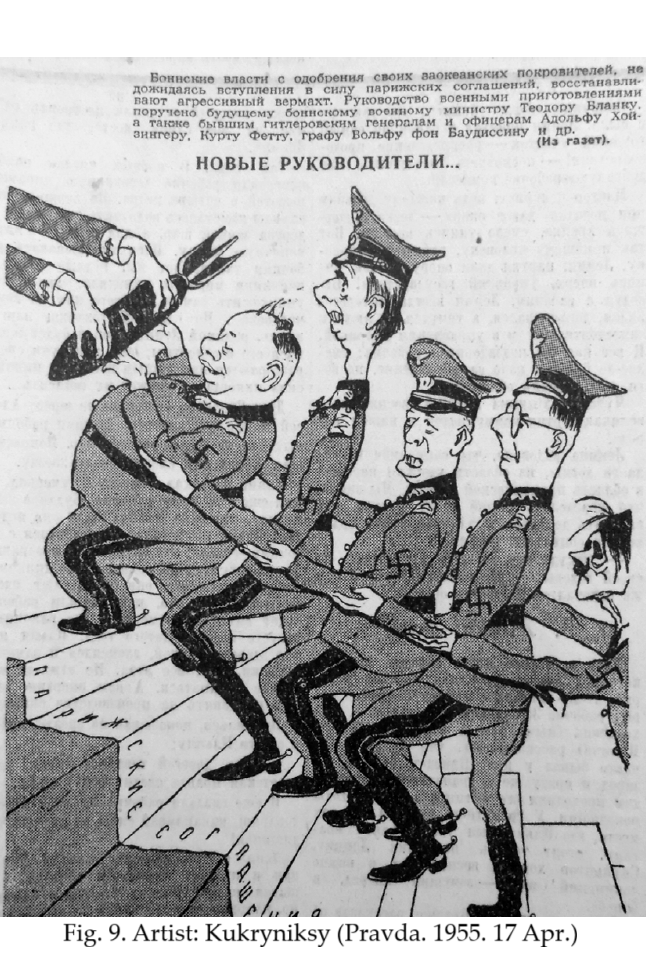

For the fascisation of the image of the FRG there was quite an objective reason, consisting in the admission to state administration of a pleiad of generals and officials compromised not only by service to the Third Reich but also, as the Soviet side emphasised, by war crimes. This theme is most vividly revealed by the caricatures “American Seedlings” [14. 28 Dec.], “New Leaders… Former Inspirers” [20. 17 Apr.] (fig. 9), “The Return of Hans Speidel” [21. 27 Jan.], “Provocateurs of the New War Strauss, Speidel, Brentano and Their Old Shadows” [12. 17 Aug.], as well as some others, where the fascist bigwigs of the past stand side by side with post-war West German figures. Already after the resignation of Chancellor Adenauer, at the very end of 1964, with a series of three satirical drawings containing also beast-like images of former fascists, Pravda marked the news that “in West Germany judicial prosecution of Nazi criminals ‘for expiration of crimes’ is ceasing” [22. 15 Nov., 26 Dec., 27 Dec.].

Such were the main directions of the fascisation of the image of the enemy at the initial stage of the global ideological conflict. It is noteworthy that the Cold War itself was sometimes endowed with the features of a caricatured fascist—it was a shapeless, half-melted snowman with a Wehrmacht helmet on its head and a gun barrel instead of a nose [10. 22 Dec.; 15. 3 May]. Episodically, Hitler or fascist symbolism was depicted in caricatures of Churchill and the conservative circles of Britain, of the unfriendly to the USSR regimes of Japan, South Korea and Portugal, or, for example, of the inspirers of the anti-communist revolt in Hungary in the autumn of 1956. This method of visual exposure was also applied in the subsequent period, touching upon all sorts of juntas, and even the actions of Israel in the Lebanon War of 1982.

Already at the beginning of the 1960s, veterans of Soviet satire noted how symbolic and in a certain sense routine such drawings had become for them. B. Efimov wrote that “such stencil figures as the British lion, Uncle Sam, the warmonger with the atomic bomb in his teeth, the German revanchist in a horned helmet (emphasis mine—E.F.) and the like, long since familiar and tiresome personages” still retain relevance as traditional image-metaphors that have acquired the character of “a kind of satirical terminology” [5. P. 58]. In 1962, looking back on their 30 years of work in Pravda, the Kukryniksy recalled how with the beginning of the Cold War “there appeared also a new ‘model,’ which replaced the devilishly tiresome Hitler. And recently the old Hitlerite ‘models’ have crawled out again—the Speidels, the Heusingers, and the other Strausses” [23. 19 Apr.]. All this testifies to the fact that the perception once embedded in visual propaganda had a noticeable influence both on its authors and, ultimately, on its viewers.

Were the proposed images convincing, one can indirectly judge from the letters of some Soviet citizens sent to the higher leadership of the USSR against the background of various events of the Cold War. In the light of N.S. Khrushchev’s visit to Austria in July 1960, former front-line soldier M. Ryazanov, referring to personal observations, wrote to the General Secretary that fascists in this European country openly and unhindered spread their appeals, and at the New Year’s ball of 1956 in one of the clubs “they scattered sweets with the image of the swastika.” He also reminded of those arriving from Austria, “bandits of fascism,” who replenished the ranks of the Hungarian insurgents, and drew a very telling conclusion: “…fascist thugs can act even now, and they, being incited by the American aggressors, can commit any abomination” [24. L. 120]. At moments of rising international tension, ordinary people, as was often found also in visual propaganda, drew historical parallels: “if Eisenhower sharpens steel bayonets on us, then like Hitler he will perish many times faster” [24. L. 80]. Or, for example, a judgement on the Caribbean Crisis: “…between Hitler then and Kennedy now, unfortunately, there is too little difference… all our concessions today will return as betrayal in relation to the courageous, heroic, beautiful Cuban people… By this we shall not save peace, just as we did not save it once, conceding Czechoslovakia to Hitler” [25. L. 79–80]. At the same time, some authors looked with optimism at the social movement of capitalist countries, which was also in the spirit of Soviet internationalist slogans. Thus, a letter from a certain A. Naumov from Leningrad, written in the summer of 1962, expressed the hope that peoples “will fight against capitalists of all kinds, wherever they may be and under whatever mask they may hide—under fascists, militarists, ultras, and so on” [26. L. 34–35]. But in some cases the fascisation of the perception of the enemy even surpassed the limits assigned by official propaganda. For example, after the murder at the beginning of 1961 of the leader of the Congolese national-liberation movement P. Lumumba, the culprits of this crime—Western colonisers and their African supporters—were called fascists [27. L. 10]. And the UN General Secretary D. Hammarskjöld, who, it was believed, being in collusion with the West, permitted the execution, was also proposed “to be judged as an old fascist” [Ibid. L. 32]. And although at that time dozens of caricatures were being published exposing colonialism, a reference to fascism in them was not observed.

Despite a certain similarity of the above judgements with the picture of the world proposed by visual propaganda, on the whole it would, however, be not quite correct to link the emergence among the population of “fascist analogies” exclusively with any propagandistic devices. For the majority of Soviet people of that generation, the struggle against fascism was, above all, a personal experience and a tragedy, the mention of which in letters was a consequence also of deeper psychological anxieties about the further fate of their country and the world.

In our day, researcher S. Kara-Murza noted, though with a share of irony, that attempts at deep scientific analysis of fascism sometimes encounter the argument: “…after all, the Kukryniksy have explained everything to us” [1. P. 12]. What exactly could caricaturists “explain” to society? The undertaken analysis showed that, in essence, the Cold War in the visual propaganda of the USSR began precisely with an allusion to the echoes of fascism still resounding on the political arena of post-war Europe. At the same time it acquired the character of a kind of archetypical evil, to which, from the Soviet point of view, almost everyone who took an openly unfriendly path was related. In this case the role of fascist symbolism as such can be defined in two ways: on the one hand, to fix and strengthen the negative essence of antagonistic images, and on the other—to create them initially through the special semantic load of the symbols themselves. Therefore, fascism here is no longer a specific regime or ideology, but a symbolic category meaning a definite political behaviour. In accordance with the plots of posters and caricatures, to the typical qualities of this behaviour should be attributed: a course towards the betrayal of class or national interests, the construction of personal dictatorship, the cultivation of aggressive social psychology, the waging of offensive wars, orthodox anti-communism, militarism and revanchism, as well as any measures de facto rehabilitating Nazism. Applied to the present, the propaganda experience considered testifies that in the situation of information wars in principle any political force, which consciously or unconsciously falls under the above-named features, at the mental level can be associated in the mass consciousness with fascism.

___________________________________________________

NOTES [shown in superscript in the text—KO]

1: See, for example, the posters by G. Roze “Capital Facing the USSR” (1930); V. Deni “Erase from the Face of the Earth the Enemy of the People Trotsky and His Bloody Fascist Gang” (1937).

2: Hüseyin Cahit Yalçın – pro-Western Turkish writer and public figure, anti-communist; Władysław Anders – Polish nationalist general; Francisco Franco – Spanish dictator; chitoses – Greek ultrarightists.

3: See, for example, I. Semenov “We Meet the Enemy Simply…” (1948); V. Briskin “A Lesson to the Enemies” (1952), “In the Soviet Sea the Enemy’s Woe” (1953); S. Zabaluev “Let Us Remind the Aggressors Just in Case” (1955).

4: Representatives of the Pentagon were depicted together with images bearing fascist symbolism in 65 caricatures.

5: See the posters by V. Briskin “On the Hitlerite Path… One Road, One End…” (1952) and “On the Old Fascist Road…” (1953), as well as the caricatures of the Kukryniksy “On the Path of Hitlerite Tyranny” [18. 19 May] and “The Branded” [18. 24 Dec.].

6: See, for example, L. Samoilov “Hands Off!” (1952) and B. Shirokorad “The Bell-Ringers of War” (1962).

7: See, for example, S. Zabaluev “For the Friendship of the Soviet and German Peoples! In the Name of Peace in the Whole World!” (1953); V. Koretsky “Long Live the Friendship of the Peoples of the Soviet Union and the German Democratic Republic” (1958).

REFERENCES

- Kara-Murza S.G. German Fascism and Russian Communism: Two Totalitarianisms, in Communism and Fascism: Brothers or Enemies? : collection / ed.-comp. I. Pykhalov. Moscow, 2008. P. 7–57.

- Wippermann W. European Fascism in Comparison 1922–1982. Novosibirsk, 2000. URL: http://lib.ru/POLITOLOG/fascio.txt, free (accessed: 04.03.2017).

- Vakhitov R.R. Nationalism: Essence, Origin, Manifestations. URL: http://redeurasia.narod.ru/biblioteka/nacionalizm.html, free (accessed: 04.03.2017).

- Efimov B.E. True Stories. Moscow, 1976. 221 p.

- Efimov B.E. Fundamentals of Understanding Caricature. Moscow, 1961. 69 p.

- Efanov L.D. My 22 June 1941 // We Shall Not Forget the Dear Frontline Roads: Memoirs of Participants of the Great Patriotic War – Veterans of Tomsk State University. Tomsk, 2004. P. 74–80.

- Fedosov E.A., Konev K.A. Soviet Poster of the Time of the Great Patriotic War: National and Regional Aspects // Rusin. 2015. No. 2 (40). P. 189–210.

- Pravda. 1960.

- Pravda. 1946.

- Pravda. 1959.

- Pravda. 1963.

- Pravda. 1961.

- Pravda. 1950.

- Pravda. 1953.

- Pravda. 1958.

- Efimov B.E. Ten Decades: About What I Saw, Experienced, Remembered. Moscow, 2000. 672 p.

- Pravda. 1949.

- Pravda. 1952.

- Pravda. 1962.

- Pravda. 1955.

- Pravda. 1957.

- Pravda. 1964.

- Soviet Culture. 1962.

- State Archive of the Russian Federation (hereafter – GARF). Fund: R5446. List: 94. File: 1278.

- GARF. Fund: R5446. List: 96. File: 1354.

- GARF. Fund: R5446. List: 96. File: 1356.

- GARF. Fund: R7523. List: 78. File: 140.

The article was submitted by the scientific editorial board “History” on 26 March 2017.

So Stalin had nothing to do with “fascism”? I’d like to refer the readers to two books, and a Web paper.

Fascism, Stanley G. Payne; Univ. of Wisconsin Press, 1980

Liberal Fascism, Jonah Goldberg; Doubleday, 2007 — I think it was Goldberg who wrote that … anything Stalin didn’t like, he called ‘fascist’.

Also see China: The First Mature Fascist State, Michael Ledeen, 1/20/2011, https://www.fdd.org/analysis/2011/01/20/china-the-first-mature-fascist-state/

Classic 19th Century Marxism might not have been “state-ist” — fascist — but to implement it required making (Mussolini’s) The State into the supreme authority. And since The State must be run by human beings, being supreme automatically consigned it to a process of utter corruption.

Marxism was class warfare. Implementation dispensed with the old, and recreated the hegemony into a merely-new form.

LikeLike