By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 12 August 2025

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 29 March 2021

Tsar Pavel I

A few days ago, it was the 220th anniversary of the palace coup that, in the early hours of 24 March 1801, deposed the Russian Tsar, Pavel (Paul) I, the last of the Russian monarchs to fall in this way.[1] Continue reading

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 9 August 2020

Conrad of Montferrat … imagined. Picture is from the Paris of the 1840s, by François-Édouard Picot.

Conrad of Montferrat, the monarch of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, one of the four Crusader principalities, was assassinated in Tyre on 28 April 1192 by the Nizari Ismailis, the legendary Assassins. The event received a lot of interest in its own time and since in the Christian world—and fuelled the various myths about the Nizaris either being focused on the Crusaders (the Nizaris’ war was always with the Sunni order) or operating in Europe (which they never did). There has also long been speculation about a third party having sponsored the Nizaris, and a paper by Patrick A. Williams examines this issue. Continue reading

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 20 May 2018

Bernard Lewis, the great historian of the Middle East, died yesterday, aged 101.

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on January 27, 2017

The Islamic State’s June 2014 declaration that the areas it controlled were the restored “Caliphate” was seen by many as a novel development. In fact, “the State” was declared in October 2006. The next month, the predecessor of the Islamic State (IS), Al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia (AQM), dissolved itself, and a month after that the claim to statehood was expanded upon—while being wilfully ambiguous about the caliphal pretensions—in the first speech by the then-emir, Hamid al-Zawi (Abu Umar al-Baghdadi). Similarly, though confusion remains on the point, it was in this same period that the symbol of the Islamic State, its black flag, was established.

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on August 24, 2015

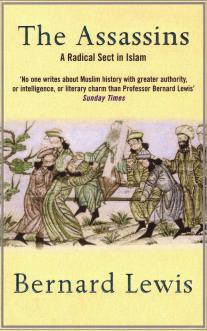

Book Review: The Assassins: A Radical Sect in Islam (1967) by Bernard Lewis

This review can be read in six parts: one, two, three, four, five, and six.

Abstract

The fourth Caliph, Ali, was assassinated during a civil war that his supporters, Shi’atu Ali (Followers of Ali), lost to the Umayyads, who thereafter moved the capital to Damascus. The Shi’a maintained that the Caliphate should have been kept in the Prophet’s family; over time this faction evolved into a sect unto themselves, which largely functioned as an official opposition, maintaining its claim to the Caliphate, but doing little about it. Several ghulat (extremist) Shi’a movements emerged that did challenge the Caliphate. One of them was the Ismailis. Calling themselves the Fatimids, the Ismailis managed to set up a rival Caliphate in Cairo from the mid-tenth century until the early twelfth century that covered most of North Africa and western Syria. A radical splinter of the Ismailis, the Nizaris, broke with the Fatimids in the late eleventh century and for the next century-and-a-half waged a campaign of terror against the Sunni order from bases in Persia and then Syria. In the late thirteenth century the Nizaris were overwhelmed by the Mongols in Persia and by the Egyptian Mameluke dynasty which halted the Mongol invasion in Syria. The Syrian-based branch of the Nizaris became known as the Assassins, and attained legendary status in the West after they murdered several Crusader officials in the Levant. Attention has often turned back to the Assassins in the West when terrorist groups from the Middle East are in the news, but in the contemporary case of the Islamic State (ISIS) the lessons the Nizaris can provide are limited. Continue reading

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on August 18, 2015

This is the second of a six-part series. For part one, see here.

Alamut fortress, northern Iran, the headquarters of the Nizaris

The Origins of the Nizaris in Persia

Hassan-i Sabbah would lead the Nizaris in Persia. Recruited in Rayy, near Tehran, by the chief dawa (missionary) of the Fatimids in 1072, Hassan-i Sabbah went to Egypt between 1078 and 1081, before returning to Iran to proselytize. In 1090, Hassan-i Sabbah won control of the fortress of Alamut in north-west Iran, which would become the headquarters of the Nizaris. Throughout the 1090s, the Nizaris gained control of further castles in Daylam, specifically the Rudbar area; in the southwest of Iran between Khuzestan and Fars; and in the east in Quhistan. Most impressive was the capture of the fortress at Shahdiz, near Isfahan, in 1096-7.

The Daylamis were a notoriously rebellious and hardy people; one of the last to convert to Islam, they were then among the first to assert their independence within it, first politically by forming a separate dynasty and then religiously by converting to Shi’ism. Continue reading

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on May 7, 2015

With the triumph of relativism and the current economic woes of the West, the sense that Western civilization is unique and in some respects—to use an old-fashioned word—better than the alternatives, and worth defending and exporting, is waning. But Bernard Lewis’ The Muslim Discovery of Europe suggests a longer view in which Europe, while containing all the faults of previous civilizations, has been one of the few to begin the process of correcting those faults, and has corrected many more than any other civilization.

One feature of European civilization that stands out as unique is curiosity. Continue reading