By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 26 January 2026

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 17 January 2019

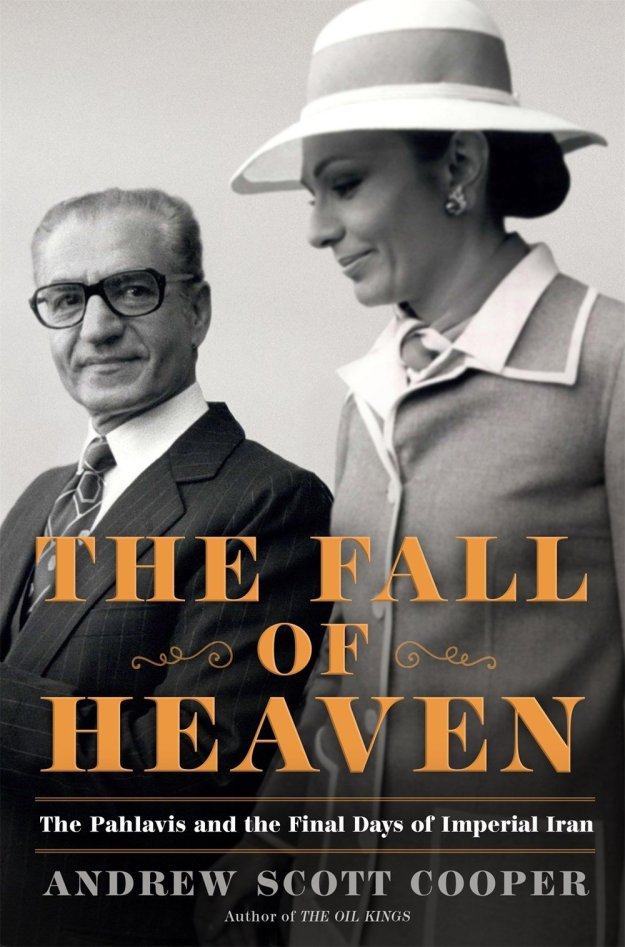

Forty years ago yesterday, Muhammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah (King) of Iran, left his country for the last time as a year-long revolution crested. A month later, the remnants of the Imperial Government collapsed and Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was swept to power after his long exile, establishing the first Islamist regime. Andrew Scott Cooper’s 2016 book, The Fall of Heaven: The Pahlavis and the Final Days of Imperial Iran, charts how this happened. Continue reading

This article was originally published at The Brief

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 26 October 2018

At the beginning of September, New America published a paper, based on recovered al-Qaeda documents, which concluded that there was “no evidence of cooperation” between the terrorist group and the Islamic Republic of Iran. New America’s study lauds itself for taking an approach that “avoids much of the challenge of politicization” in the discussion of Iran’s relationship with al-Qaeda. This is, to put it mildly, questionable.

A narrative gained currency in certain parts of the foreign policy community during the days of the Iraq war, and gained traction since the rise of the Islamic State (IS) in 2014, that Iran can be a partner in the region, at least against (Sunni) terrorism, since Tehran shares this goal with the West. Under President Barack Obama, this notion became policy: the US moved to bring Iran’s revolutionary government in from the cold, to integrate it into the international system. Continue reading

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 18 March 2018

Jihadists on parade in Ramadi, 18 October 2006, to celebrate the declaration of the Islamic state (image source: Al-Jazeera)

After the formation of the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI), the leader, Hamid al-Zawi (Abu Umar al-Baghdadi), made his first speech on 23 December 2006. An English translation of the speech was released by ISI and is reproduced below. Continue reading

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on June 9, 2015

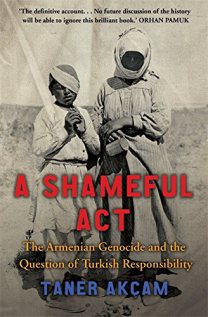

This is the complete review. It has previously been posted in three parts: Part 1 on the question of whether the 1915-17 massacres constitute genocide; Part 2 on the post-war trials and the Nationalist Movement; and Part 3 gives some conclusions on what went wrong in the Allied efforts to prosecute the war criminals and the implications for the present time, with Turkey’s ongoing denial of the genocide and the exodus of Christians from the Middle East.

A Question of Genocide

The controversy over the 1915-17 massacres of Armenian Christians by the Ottoman Empire is whether these acts constitute genocide. Those who say they don’t are not the equivalent of Holocaust-deniers in that while some minimize the figures of the slain, they do not deny that the massacres happened; what they deny is that the massacres reach the legal definition of genocide. Their case is based on three interlinked arguments:

Taner Akcam’s A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility presents evidence to undermine every one of these arguments. Continue reading

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on June 7, 2015

Post-War Turkey

The last foreign troops left Istanbul on October 2, 1923. On October 6, Turkish troops re-occupied Istanbul, and on October 13 the Turkish capital was moved to Ankara. The independence struggle won, the focus now turned to the form independence would take.

Having already abolished the Sultanate—that is the executive post held by the House of Ottoman—Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk) abolished the Caliphate on March 3, 1924. Atatürk also scrapped the office of Şeyh-ül İslam, banished the House of Ottoman (packing Sultan Abdülmecid onto the Orient Express), and closed the separate religious schools on the same day. The ulema had given much ground during the reforms of the nineteenth century but they had also frustrated and defeated many reformers; Atatürk would not be one of them. The promulgation of the Republican Constitution on April 20, 1924, confirmed parliamentary supremacy over the shari’a, secular law over theocracy.

In the late 1920s, further reforms were made. The fez, which “had become the last symbol of Muslim identification,” was banned. Atatürk had said the fez was “an emblem of ignorance … and hatred of progress”. Turks would wear the costume “common to the civilized nations of the world,” which is to say Europe. Atatürk adopted the Swiss legal code, which removed the Holy Law from personal status—abolishing polygamy, making both parties to a marriage equal, allowing divorce, and allowing people to change their religion. Islam was disestablished as the State religion, and as the final step the Arabic script was changed to Roman. The connection with the East was broken, and Turkey was firmly oriented West. Continue reading