By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 28 February 2019

Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, founder of the Qajar dynasty (1794-1925) in Iran [source]

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 28 February 2019

Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, founder of the Qajar dynasty (1794-1925) in Iran [source]

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on 27 February 2018

Review of ‘Jefferson’s War: America’s First War on Terror, 1801-1805’, by Joseph Wheelan

“The Terror,” raids by pirates who believed themselves to be on a holy mission, were “an accepted hazard of conducting foreign trade, much like hurricanes”. So notes Joseph Wheelan in his 2004 book, Jefferson’s War. That changed after a naval expedition by the United States put down the trade in the first two decades of the nineteenth century. Continue reading

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on January 27, 2017

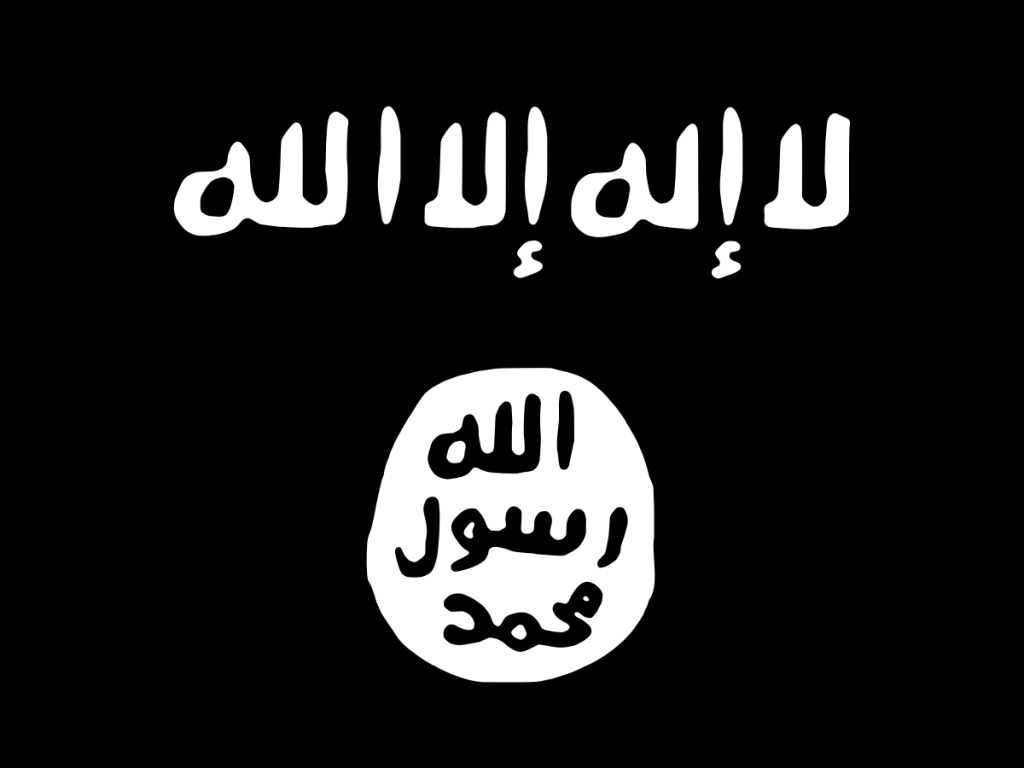

The Islamic State’s June 2014 declaration that the areas it controlled were the restored “Caliphate” was seen by many as a novel development. In fact, “the State” was declared in October 2006. The next month, the predecessor of the Islamic State (IS), Al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia (AQM), dissolved itself, and a month after that the claim to statehood was expanded upon—while being wilfully ambiguous about the caliphal pretensions—in the first speech by the then-emir, Hamid al-Zawi (Abu Umar al-Baghdadi). Similarly, though confusion remains on the point, it was in this same period that the symbol of the Islamic State, its black flag, was established.

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on March 20, 2016

Tom Holland’s In the Shadow of the Sword: The Battle for Global Empire and the End of the Ancient World (2012) is a smooth read, a feat hardly foreordained in a book that exceeds 500 pages in length. Holland writes narratively, giving his interpretation of the most likely scenario of Islam’s origins—and then presents the extended evidence and debates in endnotes for those who wish to dig into the weeds. This has gotten him into trouble among haughtier reviewers for writing “pop history”, which appears to mean an exploration of the past that there is a danger people will want to read.

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on August 24, 2015

Book Review: The Assassins: A Radical Sect in Islam (1967) by Bernard Lewis

This review can be read in six parts: one, two, three, four, five, and six.

Abstract

The fourth Caliph, Ali, was assassinated during a civil war that his supporters, Shi’atu Ali (Followers of Ali), lost to the Umayyads, who thereafter moved the capital to Damascus. The Shi’a maintained that the Caliphate should have been kept in the Prophet’s family; over time this faction evolved into a sect unto themselves, which largely functioned as an official opposition, maintaining its claim to the Caliphate, but doing little about it. Several ghulat (extremist) Shi’a movements emerged that did challenge the Caliphate. One of them was the Ismailis. Calling themselves the Fatimids, the Ismailis managed to set up a rival Caliphate in Cairo from the mid-tenth century until the early twelfth century that covered most of North Africa and western Syria. A radical splinter of the Ismailis, the Nizaris, broke with the Fatimids in the late eleventh century and for the next century-and-a-half waged a campaign of terror against the Sunni order from bases in Persia and then Syria. In the late thirteenth century the Nizaris were overwhelmed by the Mongols in Persia and by the Egyptian Mameluke dynasty which halted the Mongol invasion in Syria. The Syrian-based branch of the Nizaris became known as the Assassins, and attained legendary status in the West after they murdered several Crusader officials in the Levant. Attention has often turned back to the Assassins in the West when terrorist groups from the Middle East are in the news, but in the contemporary case of the Islamic State (ISIS) the lessons the Nizaris can provide are limited. Continue reading

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on June 9, 2015

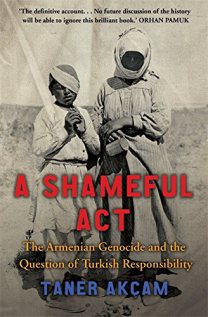

This is the complete review. It has previously been posted in three parts: Part 1 on the question of whether the 1915-17 massacres constitute genocide; Part 2 on the post-war trials and the Nationalist Movement; and Part 3 gives some conclusions on what went wrong in the Allied efforts to prosecute the war criminals and the implications for the present time, with Turkey’s ongoing denial of the genocide and the exodus of Christians from the Middle East.

A Question of Genocide

The controversy over the 1915-17 massacres of Armenian Christians by the Ottoman Empire is whether these acts constitute genocide. Those who say they don’t are not the equivalent of Holocaust-deniers in that while some minimize the figures of the slain, they do not deny that the massacres happened; what they deny is that the massacres reach the legal definition of genocide. Their case is based on three interlinked arguments:

Taner Akcam’s A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility presents evidence to undermine every one of these arguments. Continue reading

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on May 7, 2015

With the triumph of relativism and the current economic woes of the West, the sense that Western civilization is unique and in some respects—to use an old-fashioned word—better than the alternatives, and worth defending and exporting, is waning. But Bernard Lewis’ The Muslim Discovery of Europe suggests a longer view in which Europe, while containing all the faults of previous civilizations, has been one of the few to begin the process of correcting those faults, and has corrected many more than any other civilization.

One feature of European civilization that stands out as unique is curiosity. Continue reading

By Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) on January 13, 2015

Richard Bell’s Introduction to the Qur’an is, at less than 200 pages, a brief and easily-digestible explanation of the context in which Islam’s “holy” book arose, and the problems of reconciling theological orthodoxy with historical accuracy. More than six decades after publication, the book remains influential in scholarship of the Qur’an. Continue reading